War of 1812 Pensions Part 1

2

2Mar

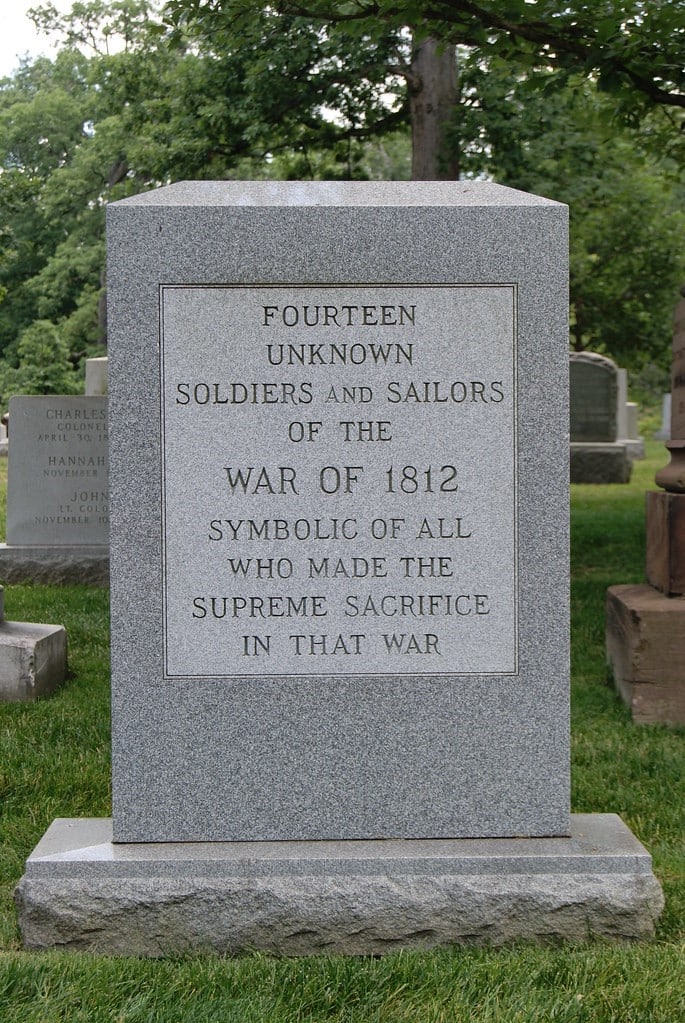

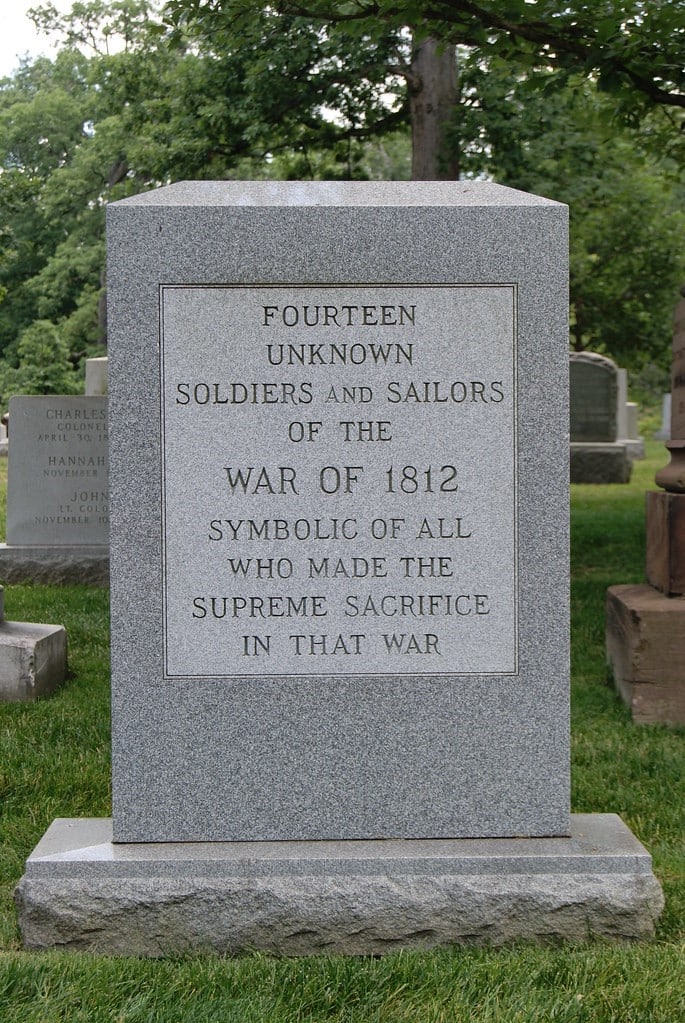

In June of 1812, the U.S. declared war against Britain, a war that would last until 1815. The War of 1812 is sometimes known as the second Revolution. The tensions that led to the war were related to Britain not recognizing the U.S. as its own country. The men who were injured in this war, and the widows and orphans who lost husbands and fathers in this war were entitled to pensions. Eventually, pensions became available to any veteran or widow of this war. If your ancestor applied for a War of 1812 pension, this article series is for you. It will go over the application process your ancestors had to go through, what you can discover in pension records, and where you can find your ancestor’s pension.

In June of 1812, the U.S. declared war against Britain, a war that would last until 1815. The War of 1812 is sometimes known as the second Revolution. The tensions that led to the war were related to Britain not recognizing the U.S. as its own country. The men who were injured in this war, and the widows and orphans who lost husbands and fathers in this war were entitled to pensions. Eventually, pensions became available to any veteran or widow of this war. If your ancestor applied for a War of 1812 pension, this article series is for you. It will go over the application process your ancestors had to go through, what you can discover in pension records, and where you can find your ancestor’s pension.

History/process

An act of 1806 for invalids of the Revolutionary War extended to invalids of the War of 1812; consequently, there was no act specifically for invalids of the War of 1812. This meant that veterans who had been injured or disabled in war service and widows of soldiers who were killed in the war qualified for pensions. It wasn’t until 1871 that the laws were changed to expand who was eligible. By the act of 1871, a soldier had to have served 60 days and been honorably discharged. Widows were eligible if they married before 17 February 1815 when the peace treaty was ratified. Eligibility was further expanded in 1878 to soldiers who’d served at least fourteen days and to widows regardless of their marriage date to the soldier.

Most men who served in the war were between the ages of 18 and 30, creating a birth year range of 1782 to 1796. However, a few men were as young as ten or as old as 70, expanding the possible birth year rage to 1742 to 1804. If your ancestor served in the war, he or his wife would only have a pension if he was wounded or killed in the war; or if he or his widow lived to the 1870s. Not many veterans would have been alive by 1871, so this was the likely reason for the government to expand eligibility.

In 1871 and 1878, a lot of people who weren’t qualified before were now eligible for pensions, so they began applying. This was the case for Anthony Wayne McKinney (1794-1873/74) who served in Captain Samuel McCormick’s company of U.S. Rangers under the command of Col. Charles Gratiot. He filed for a pension in 1872 and was approved on 7 March. He received back pay from 14 February 1871 when he became eligible. The pension of $8 per month ($194.62 in 2023 dollars) continued until 20/26 August 1873/74, when he died. There were discrepancies among the pension documents on some of the dates.

Anthony’s widow, Catharine, was not eligible for a widow’s pension until the act of 1878 was passed. She and Anthony married 7 April 1858, about three years after Anthony’s previous wife Elizabeth died. Because their marriage was after the ratification of the peace treaty, Catharine did not qualify for a pension under the 1878 act. However, she tried requesting back pay of the pension to her husband’s death in 1873/74, but this was denied.

For a soldier to qualify for a pension, he had to prove his service. Anthony did this by providing discharge papers, which stated he re-enlisted on 25 October 1813 at Dayton, Ohio (having served previously in the same U.S. Rangers company for a year with Capt. John Hopkins under Col. George Croghan’s command), and was discharged 25 October 1814 at Fort Malden, Upper Canada (Ontario). This proof of service often comes through muster rolls, which neither Captains Hopkins’ nor McCormick’s company had kept. Among the pension papers, a “Declaration of Soldier for Pension” states that he “served both years in the then Territory of Michigan and the Canadas – was at Holmes Battle on River Thames, at Point Applay and other Engagements on the Boarders of the Lakes.” This sounds like he participated in the Battle of Longwoods (4 March 1814), which is marked by the Battle Hill National Historic Site in Ontario, Canada.

Widows and orphans applying for pensions not only had to prove the soldier’s service, but also their relationship to the soldier. A widow had to show evidence of her marriage to the soldier and proof of his death. Some families did this by sending in pages from their family bible. Some states legally recognized common law marriages.

If the pension was rejected, the ancestor may have provided more information to prove their eligibility. This additional information was no guarantee that their pension would be granted, but it did make a nice paper trail for professional genealogists.

When the pension was approved, the ancestor or their agent would go to the pension office to collect the pension payment. In the case of the McKinneys, this was the pension office in Indianapolis, Indiana. After the pensioner died, the heirs would collect the final payment or make the final settlement. This payment would include the money owed between the last payment collected and the death of the pensioner.

If an ancestor moved after service, they would have had to apply for a pension through the state they served in rather than the state they were currently living in.

Contents of pension records

Because the soldier had to prove service in his pension application, there is typically information about the soldier’s name and rank, what unit the soldier served in, who he served under, and who he served with. Pension applications also contain bounty land applications, correspondence from the pension office, legal correspondence, and rejection letters. Witnesses may have been fellow soldiers. Often muster rolls are included, which indicate when a soldier was present or absent and the reason for the absence. If the soldier got wounded or sick during their service, there would be records about that, especially if that was why the soldier was eligible for their pension. The pension may also contain information about the soldier’s occupation and birth.

Anthony’s discharge papers stated that he was a farmer, born in Kentucky, and was twenty years old. It even gave a physical description of him: he was five feet-ten inches tall, had light hair, dark eyes, and of light complexion.

Pensions of widows and heirs include kinship information, and sometimes contain dates and places for all three vital events. Catharine McKinney’s widow’s pension gives her marriage date to Anthony McKinney and mentions that he had previously been married to Elizabeth Bracken who died October 1855. The pension application also gives Catharine’s surname as Morrical, from her earlier marriage. Other vital information provided are the death dates of Catharine and Anthony: she died in 1909 and he died in 1873/74. In a letter in 1880, Catharine indicated that she was sixty years old, putting her birth year in 1820. She mentioned in that same letter that she had six children and five were living. These clues would be highly valuable for any researcher learning about that family. Not only are multiple vital dates given, but the maiden names of both Anthony McKinney’s wives are also given. Catharine’s references to her children offer clues to tracing them further.

There’s more that can be found in your ancestor’s pension, but that will be explored in the next blog post in this series. The next blog will also go over how you can obtain your ancestor’s pension.

By Katie

Resources

- Anthony W. McKinney (Pvt Capt Samuel McCormick US Rangers, War of 1812), pension nos. SO11162, SC13803, WO22409, 24042; War of 1812 Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, digital images, Fold3 (https://fold3.com : accessed 10 February 2023); citing NARA collection 564415.

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/revolutionary-war-series-4-of-5-records-created-by-the-revolutionary-war-after-the-war-pensions/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/accessing-national-archives-military-records-from-start-to-finish/?search=national%20archives

- https://www.legalgenealogist.com/2013/12/04/the-marriage-and-the-pension/

- https://www.legalgenealogist.com/2013/03/30/chasing-that-pension-file/

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/what-does-that-really-say-records-analysis-1812-military-pension

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/series/a-call-to-arms-researching-revolutionary-war-ancestors

- https://www.archives.gov/files/research/military/army/dc/m313.pdf

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/resources-for-researching-your-war-of-1812-ancestor-online-part-1

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/resources-for-researching-your-war-of-1812-ancestor-online-part-2

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/the-war-of-1812-records-preserving-the-pensions/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_of_1812