The 1950 Census

1

1Apr

Since 1790, the federal government has been counting of the population by taking a census every decade. Over the years, the information gathered in the censuses has changed, based on what the government felt was important to track at different times. This has left a wonderful paper trail for genealogists. By finding a family on multiple censuses, a researcher can track a family’s movements and growth, and glean clues for further research. With the release of the 1950 census, the scope of census research is expanding. The 1950 census was released on many websites today, April 1st. Let’s explore how.

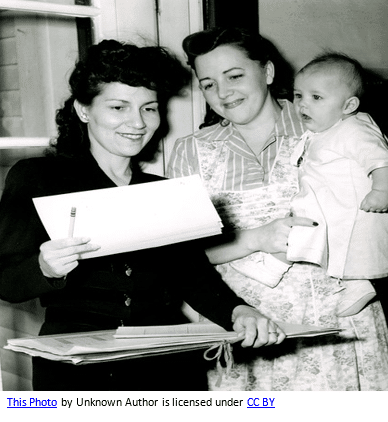

Conducting of the 1950 census

Due to the room for error in censuses, genealogists expect them to sometimes be a bit off. Ages are known to be a year or two off, sometimes more; there’s no telling who the informant was (until 1940). Additionally, moving during a census year may have caused a family to either be missed or doubly enumerated. Precautions were taken with the 1950 census to reduce such errors, so the data in the 1950 census should be accurate for genealogical research.

The organizers of the 1950 census recognized the importance of the individual enumerator in preparing data. Therefore, a lot of attention was given to training and supervising enumerators. The supervisors’ jobs included correcting mistakes made by enumerators and replacing incompetent enumerators. If those census workers did their jobs right, obvious errors that researchers may recall seeing in prior censuses should not exist in the 1950 census.

The job of counting the population of the U.S. in 1950 took about 143,000 people, around twenty thousand more than what was needed to conduct the 1940 census. With the population continuing to grow, it became increasingly more difficult and more expensive to count the U.S. population by going door to door. In 1950, some tests were done on self-enumeration in selected counties and selected enumeration districts. Of the tests conducted, the mail-in forms were the most successful. Further, some advantages were discovered to the mail-in form, including the privacy of having one household per form rather than multiple households. Mail-in enumeration became the norm for later censuses.

In previous censuses, if no one was home when the enumerator came, the data on the family may have come from a neighbor, which makes accuracy questionable. For the 1950 census, there was a set procedure for this situation which would result in more accurate data. The census taker was to ask a neighbor if anyone lived in the vacant house, when they were usually home, and if they had a telephone. The enumerator would then go back to that house, and if no one was home again, they’d leave a request to call card. The enumerator could also call the house to schedule an appointment. After several failed attempts, the enumerator would leave several Individual Census Returns (ICRs) for the family to fill out and would transcribe those onto the main census return. The families that were enumerated later had their information listed on page 71 or above (even if the enumeration district took less than 70 pages). If the enumerator did gather information on a household from a neighbor, they were to indicate in notes in the margins.

One way that people could be missing or over enumerated was confusion regarding usual place of residence, so specific rules were set up to reduce this. College students were enumerated where they lived. Prisoners were enumerated at the prisons. U.S. families that were abroad were enumerated separately from the rest of the population and counted separately for statistical purposes.

To enumerate transients, T-nights were set aside in April where enumerators would go to places transients slept, such a hotels and YMCAs. Enumerators would stay late that night and begin again the next morning, enumerating the transients who spent the night. If a transient left without being enumerated, the enumerator would gather information from the hotel registers.

Contents of the 1950 census

Compared to the 1940 censes, the 1950 census had fewer questions for the general population, and more supplemental questions for a sample of the population. This sample was increased from five percent in 1940 to twenty percent in 1950. To randomize the twenty percent, there were six different versions of the main population schedule, each with the samples in different places. This eliminated the possibility of excessive heads of households among the sample population.

The population schedule included basic information about the houses (address, if it’s a farm, etc.), names of persons in each household, their relationship to head of household, race, gender, age at last birthday, marital status, place of birth, and naturalization for foreign born.

If people were in a roommate situation, one person would be listed as head of household, and other(s) would be listed as partner.

Enumerators were instructed to assume the race of family members was the same as the informant unless told otherwise, and to ask for the races of household members not related to the head of household. They also had instructions for mixed races based on if they were black, white, Mexican, or Indian (Native American). If the parents were different races, enumerators were to go off the race of the father.

Census takers were further instructed to assume gender based on name and relationship, and only ask for the gender if names were gender neutral.

A new marital status option appeared on the 1950 census: Separated. This was for married persons who were legally separated but not divorced. This was not to include separations due to military service. A couple in a common law marriage would be enumerated as married. If an only marriage was annulled, that counted as being never married.

For the question of birthplace, the answer was to be the place the family resided at the time of birth, even for births that took place elsewhere. This could mean that a birth as reported on the 1950 census may not be the place where a birth certificate will be found.

Everyone fourteen and older was asked about employment: whether they spent more time working or keeping house, if they were looking for work, and how many hours they worked.

The supplemental questions asked to twenty percent of the population were divided between all ages and fourteen and older. The questions for all ages included where they lived a year ago (1949), places of parents’ births, highest grade of school attended and completed, if those 30 and under attended school since February.

The supplemental questions asked of people fourteen and older included more detailed questions about their work and income. Males were asked about military service, including which war they served in. Married persons were asked if they’d been married before. Women who had ever been married were asked how many children they had borne, not including stillborns (this was not supposed to include adopted or stepchildren, but enumerators only told informants this if they asked).

1950 Census Forms

Housing schedules, which asked information about the house itself, were on the backs of the population schedules. An agricultural schedule was filled out for any household that indicated they were on a farm. Unfortunately, neither of these schedules are extant. When the 1950 census was microfilmed in 1952, only the population schedule was filmed. The original paper censuses were intentionally destroyed in 1961—this was justified by the fact that the population schedules had been microfilmed and a belief that the data on the housing schedules would be of insufficient value to future researchers.

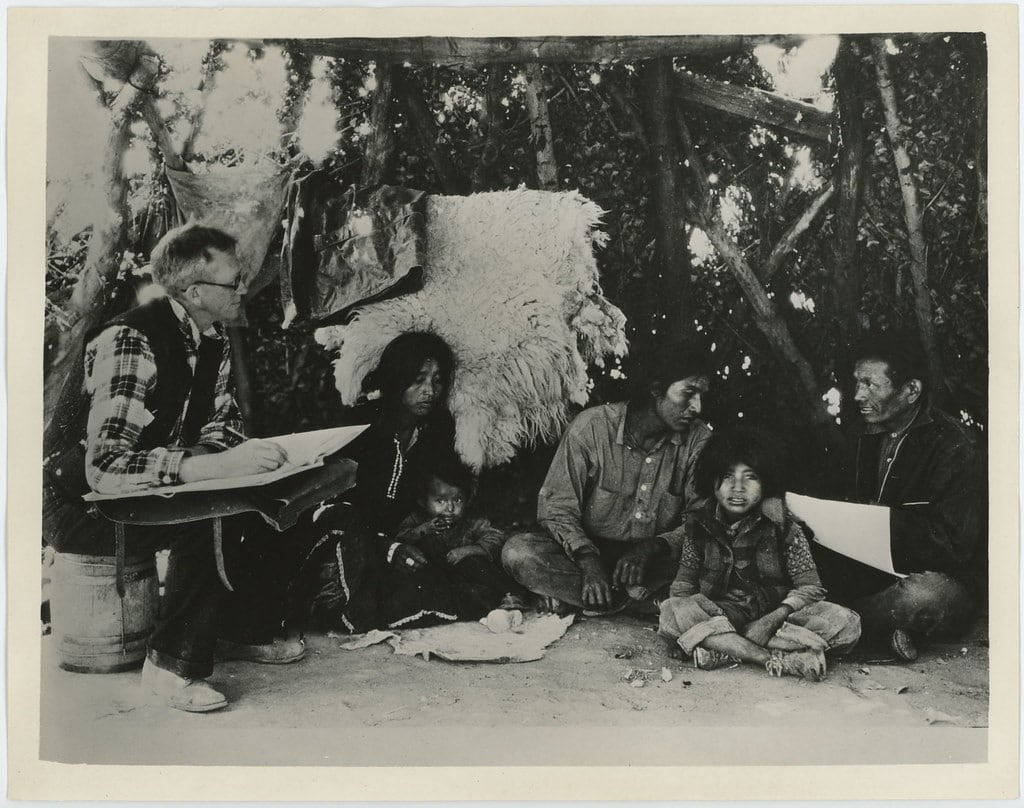

The 1950 census had different forms for Indian reservations and various U.S. territories, as well as an Individual Census Report which was mainly used by military personnel living in barracks, lighthouses, and vessels. To access blank forms, go here.

The heading of the Indian Reservation form included the reservation name. The columns on the form included places for English and tribal names, tribe and clan name, and amount of Indian blood.

Each U.S. territory had its own version of the population schedule form. Territories in 1950 included Alaska, Hawaii, American Samoa, Panama Canal Zone, Guam, Virgin Isles, and Puerto Rico. Several of these territories didn’t do supplemental questions. In many of the island territories, the birthplace column indicated whether they’d been born in that territory or the continental U.S. The form for Puerto Rico was entirely in Spanish.

Another form was infant cards, which were filled out for children born in the first three months of 1950, who were still alive on 1 April. The information on these cards included the actual birthplace of the child and the mother’s maiden name.

When determining what information to collect, the census bureau had to collect statistical information that would be of value to the nation. They also wanted to ensure high standards and minimize the burden to respondents. Cost to the government and taxpayer was also a concern.

Release of the 1950 census

The 1950 census was released to the public on April 1, 2022. Images of the population schedules will be available through NARA. For the first time, the census is being released with OCR and AI technology, which means a computer will have transcribed the data. This makes the census immediately searchable. However, computer transcriptions are not always accurate, so volunteers will need to make corrections to incorrect transcriptions. If your ancestor’s name was mis-transcribed by the computer, you can look for them by browsing location and enumeration district.

If you need help finding your ancestors on the 1950 census, Price Genealogy can help.

Katie

[i] "MM00004671" by Florida Keys--Public Libraries is licensed under CC BY 2.0

[ii] "File:1950s family Gloucester Massachusetts USA 5336436883.jpg" by Glenn from West Virginia, USA is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

[iii] "78-98(12)" by FDR Presidential Library & Museum is licensed under CC BY 2.0