Researching the Genealogy of African Americans Part One

20

20Jan

In honor of Martin Luther King day this week, we thought we would repost a two part blog on researching the genealogy of African Americans.

In honor of Martin Luther King day this week, we thought we would repost a two part blog on researching the genealogy of African Americans.

Genealogical research is fun for some people but for others it is more of a chore. With so many records online and websites to choose from, it can be exciting or daunting. With African American ancestry, even seasoned researchers will want to take a deep breath and ready themselves for an exciting challenge. So where do we even start?

As with any type of research, we always start with what we know. Solid information is the springboard for the next step: form a question about what we want to know. For example, “Where was this individual in 1930?” or “Who were his parents?” Then we begin our search. We evaluate the information that comes up when we put the name, date, and place in an online website like FamilySearch or Ancestry—then we use our own judgment and knowledge. We follow the trail of bread crumbs and glean any hints along the way, studying what other people have already gathered by searching online trees. We patiently keep track of where we have been online and what we have looked at to avoid duplicating our own efforts. But even with the best skills and methodology in place . . . researching individuals with black heritage comes with inherent challenges.

Researching African Americans typically leads to the Southern States. Following the Civil War and Reconstruction, Jim Crow and segregation laws often meant that they were treated differently than the white population, and this is reflected in the way their records were kept. There are fewer details for them on census records as well as in marriage and death records. Historical highlights concerning black communities are often sparse. The best advice to meet this challenge is to persevere. In searches, we spell their names every way we can possibly think of and then keep trying. We give the marriage or death year a generous leeway in both directions. We go through the census records page by page if we know they should be there, which is sometimes necessary if they don’t appear in the index.

So now that we have established a pedigree and some family groups, we realize the next generation was born before the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) and before the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery (1865). What is next?

A way we can possibly identify our ancestors is by looking at the records of former slave owners. We determine who the owners may have been, and often think that upon emancipation they may have taken the surname of one of their former masters. We must consider that only 15 percent of freed slaves used the family name of a former owner, and from 1865 to 1875 many African Americans changed their family name.[1]

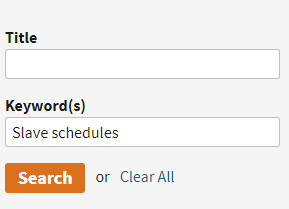

Proceeding with this in mind, we begin by using a method of comparison to narrow down the extensive list of people with the common surname. For example, if the name is Jackson, and we know our individual was born in Mississippi, we start looking for them there. A way to find a list of these people is the Slave Schedules on Ancestry. We go to the Search tab and select Card Catalog. When that screen comes up, there are two search bars, one with the word “Title” and the second shows “Keyword(s).”

We type in “Slave Schedules” in the keywords box.

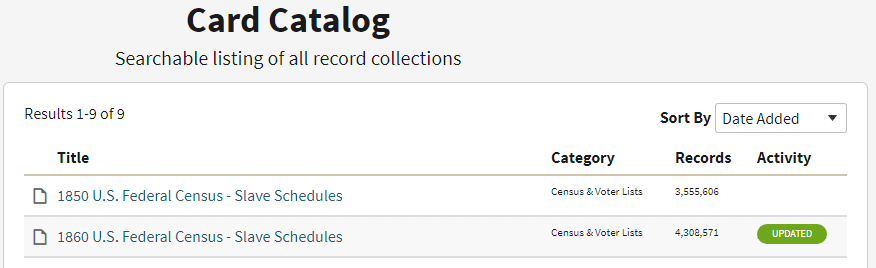

We click the search button and two choices will come up:

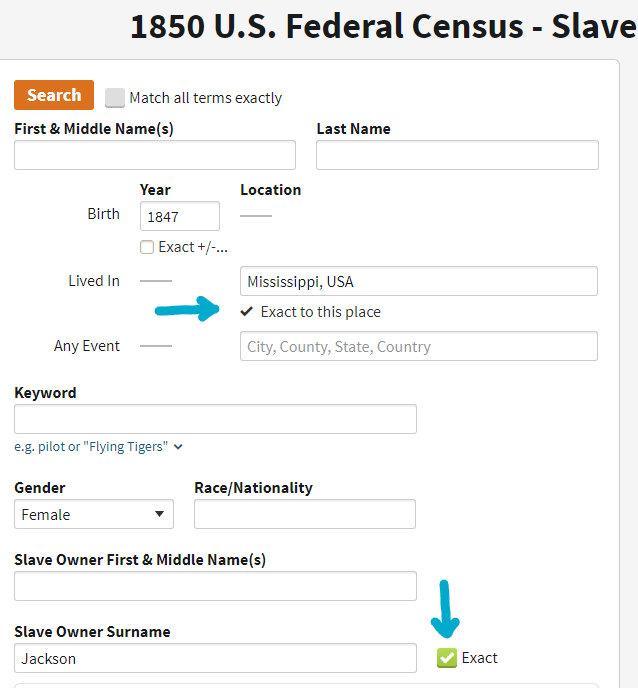

For this example, “1850 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules” has been selected. Then we fill in the Search box by adding the year of the birth of our ancestor, the state they lived in (and county if we know it) and then check the “Exact to this place” box. Add in the surname in the last box, which will identify any slave owners with the same surname as the ancestor, and again, check the “Exact” box. Then click the “Search” button.

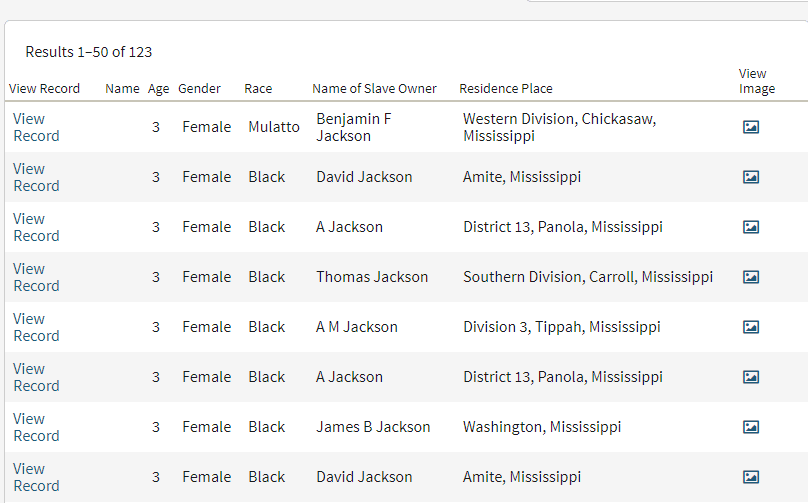

Here are our results:

This screen clip only shows the first eight out of a possible 123 records! Notice that a man named David Jackson is on the list twice, but the first 50 results shows him 11 times. This lets us know he had several slaves living and working on his property in Amite county, Mississippi, and many of them were the same age as the ancestor.

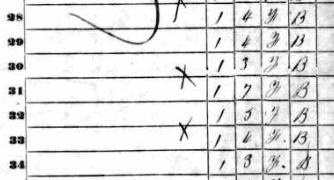

We need to keep in mind that people in these census slave schedules were identified by age and gender only, with tic marks in columns, so we just have to consider what we find as circumstantial evidence. The slaves’ first names are not given. Here is a look at a clip from one of the actual census records:

Lines 30 and 34 indicate three-year-old black females. This record is from the slave census taken in 1850 of David Jackson.

It’s important to remember at this point in our African American research that the evidence is still insufficient to positively determine any connection between these families and the sought-after ancestor. Before emancipation, it will be challenging to find slaves recorded by name in records.[2] So why do we even conduct a search?

There are exceptions to this “nameless” population. Some slaves are found in wills left by slave owners who may have described their property to be left to their heirs. The wording is harsh, but slaves were considered by their owners and the law as property. If a slave owner failed to make a will, his probate inventory may list each item of property in preparation for distribution among his or her heirs.

The expert researchers at Price Genealogy can help you with your African American genealogy. In Part 2 of this blog, we will continue the search using this method, plus discuss several other available online sources.

Beth

[1] FamilySearch Wiki, African American Research

[2] Quote from Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Finding Your Roots.

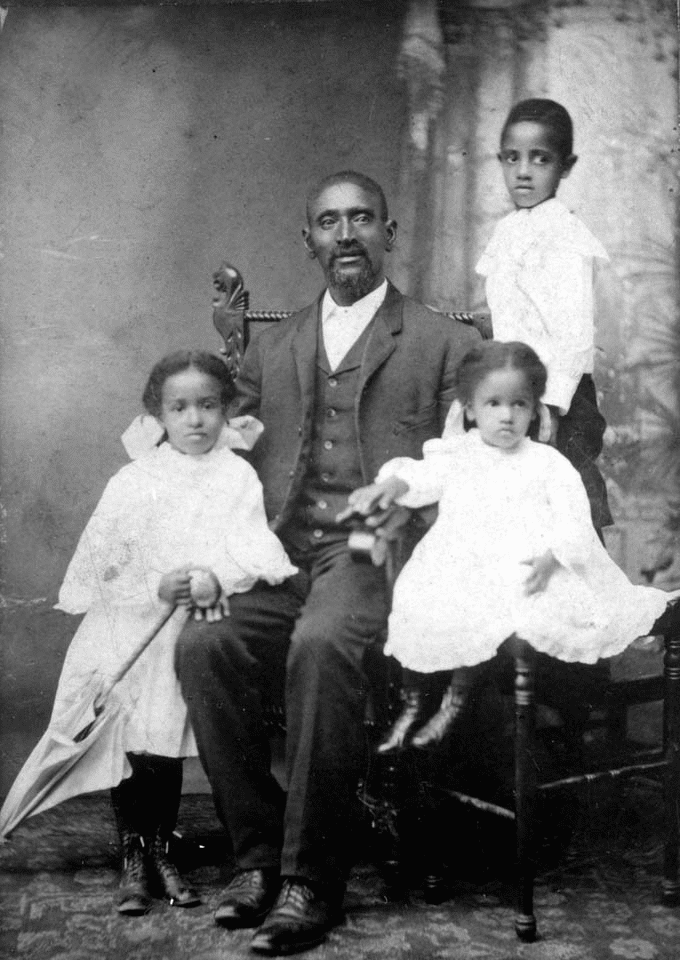

Photo in public domain Missouri State Archives, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons