Probate Records

27

27Oct

Many records are created around a person’s death: death certificate, obituary, burial records, probate records. Probate records pre-date many other kinds of death records. When a person dies owning property, the probate process distributes that property among heirs—someone who wrote a will specifying who would inherit what died testate. Someone who died without a will died intestate. In either case, a paper trail is left behind, which could be used to research your ancestors.

About probate

Probate is the judicial process used to administer and settle the affairs of a property-owning person who has died according to the jurisdiction's laws. It is the activity the family members and heirs engage in to transfer the property following the local inheritance laws. Real property is land, and personal property is belongings or movable goods. The probate process covers the transfer of both.

For someone who died testate, the deceased would have appointed an executor (executrix if it’s a woman), who would oversee executing the will once the person dies. The death would be reported to the local court, and the executor would distribute the property according to the wishes expressed in the will. For an intestate death, the court appoints an administrator to distribute the property to heirs as the court sees fit. In either case, records would name relatives.

For both testate and intestate deaths, the first step of the process is initiation. Here, the executor or administrator petitions the court or signs a bond. Next, inventory is taken, and assets are appraised. These records can give a glimpse of what ancestors owned. If the deceased owed debts, assets may be sold to pay them off. Once settled, the estate, or money from selling everything, is distributed among the heirs. The last step is a final accounting. The whole process can take years to complete.

Sometimes, the deceased left dependents behind. When this happened, care had to be established for the dependents. This could be the wife or the children. If the children were minors, guardians had to be appointed. The guardians would not necessarily be their mother. While the children may have remained with the mother, the guardian would handle the children’s inheritances until they reached the age of majority.

Inevitably, all that legal stuff left behind a paper trail. Court minute books and dockets contain court actions and orders. Loose papers may include wills, bonds, claims, receipts, correspondence, and legal notices. You may find court record books, which include registers of probate activity, indexes, will books, books of administrator or executor bonds, annual accounts, final settlements, estate inventories and sales, and guardianship appointments. You may also want to search newspapers, which may have announced upcoming estate sales and notices of probates being filed.

Legal jargon aside, these records can contain valuable information about family relationships. Relatives were often named in probate records, especially those who stood to inherit. This could include the spouse, parents, children, siblings, and in-laws. Sometimes, this may be the only record where female relatives are named. Neighbors may be mentioned, often referring to property boundaries. Probate records can also help distinguish different people with the same name and establish residency and origins. For slave owners, the probate records may identify enslaved persons by name, which can be helpful in African-American research.

The above description is somewhat generalized. Inheritance laws varied based on place and time. Wherever your ancestors lived, look up the probate laws and legal terms for their time and place. For example, different places may have different laws regarding when a child comes of age to inherit or different laws regarding if a woman could inherit. Probate laws established who could write a will and who inherited when there was not a will. These laws also determined if it was necessary to file a probate and where it was filed. Finally, the laws determine where the records are kept.

In most states, the probate process is conducted at the county courthouse where the deceased owned property. This wasn’t necessarily the same place where he lived or died. Courts that usually kept probate records (depending on the place and time) include Circuit Court, Court of Common Pleas, Court of Ordinary, District Court, Orphans’ Court, Probate Court, Surrogate’s Court, and Superior Court.

Reference information can be found at any of the following places:

In some cases, the probate records may still be at the courthouse. Sometimes, probate files are moved from the courthouse to the state archive or a local historical society. FamilySearch and Ancestry have digitized many probate records, some of which are searchable. If the probate records for your ancestors' area have yet to be indexed, you may need to browse the digital probate files. In this case, it helps to have an idea of when and where your ancestor died. It can also help to find your ancestor in a probate index first, and the index will give you the information you need to find the original probate records.

To search for probate records online, try any of the following and navigate to or search for the state or county in which your ancestor lived:

Case study

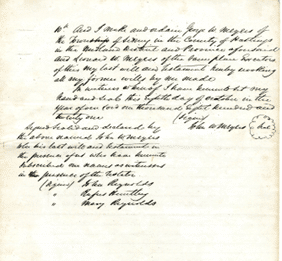

The probate indexes for Washington County, Pennsylvania, listed many Alexanders. The ancestral Joseph Alexander died between 1833 and 1834. His will was found in book five, pages 153-155.

The will of Joseph Alexander[1] mentions his wife but doesn’t give her name. It also mentions children: Joseph, James, and Fanny. Fanny Alexander was unmarried at the time the will was written. The grandchildren mentioned were Eddie/Edie Ramsey, Nancy Ramsey, and Jean/Jeane Alexander and it was stated that Eddie and Nancy were siblings. Since inheritances were going to grandchildren, it can be assumed that the parents of those grandchildren had died before the will was written. Eddie and Nancy would be the children of one of his daughters since they have different surnames. Jeane would be the daughter of one of his sons since she has the same surname. Joseph Alexander, Jr was appointed with much of the distribution of money to other relatives and was named as one of the executors. This suggests he was the oldest living son and a legal adult.

Joseph Alexander wrote his will on 12 August 1833, and it was proved on 8 September 1834. He would have died between those dates, most likely closer to the latter. Family relationships reflected in the will are the relatives who were living in August 1833. If any of them had died by the time the will was proved, there’d be a note to indicate so. Since no such note was in the probate files, it can be assumed they were all still alive in September 1834.

Associates and neighbors were also mentioned in the will. A lot left to his wife was one next to that of Moses Bell. Rents came from places where Samuel Barr and Joseph McElwaith/McElwrath lived. Eddie Ramsey was appointed to pay money to Joseph Mayes. Land had previously been sold to McNitt and Alexander. The executors were Joseph Alexander Jr and Joseph Henderson Esqr. Further research of Joseph Alexander should involve looking for those names in other records.

Based on this information about Joseph Alexander and his family, other places to research them include census records from 1830 and earlier, probate records for other Alexanders that might be related, tax records, and land records. Tax records would show when the Josephs Alexanders became adults, hinting at their possible birth years. The will mentioned a land sale, which should be reflected in land records.

If you need help researching your ancestors in probate records, contact Price Genealogy.

Katie

Resources:

- Nancy A. Peters, Beyond the Will: What Probate Records Reveal about AncestorsNGS Magazine 48 #2 (April-June 2022): 16- FHL 973 D25ngs v. 48 no. 2

- Judy G Russell, No Longer "All Greek to Me:" Dealing with Legal Lingo in Probate RecordsNGS Magazine 48 #2 (April-June 2022): 29- FHL 973 D25ngs v.48 no. 2

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States_Probate_Records

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/connecting-generations-through-probate-and-property/

- Courthouses: Raymond F. Adams, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Old_Courthouse_1862.jpg Paul Emmert, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Old_Courthouse_by_Paul_Emmert.jpg

[1] Washington County, Pennsylvania Surrogate’s Court House Recorder of Deeds, Will Book Volume 5, pp. 153-155, will of Joseph Alexander, 8 September 1834; digital image, FamilySearch, (https://familysearch.org : accessed 5 September 2022), Film #005537970, images #87-88.