Paying Their Dues : Tax Records as Genealogical Evidence

17

17Apr

It’s tax time in the United States, which means millions of people are due to file their federal income tax returns this year by April 15th. Designated by Congress in 1913, the tax deadline was first selected to be March 1st.[1] In 1918, it was changed to March 15th, and it wasn’t until 1954 that the date was finally chosen to be April 15th.

What are tax records, and why were they kept?

“… in this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes.” ~ Benjamin Franklin, 1789.[2]

The idea of taxation is nothing new. Even our ancestors thousands of years ago were required to pay taxes. Likewise, some of our ancestors weren’t happy about paying their taxes. An early example of this can be found in ancient Egypt, where a priest, complaining of excessive taxes, wrote, “It is not my due tax at all!”[3] Before the advent of coinage and paper money, taxes were paid in the form of livestock or a share of the taxpayer's crop. Labor tax was a physical requirement for early Egyptians. A man would have to work for the government throughout the year, which was a form of taxation.[3]

The earliest historical record of taxation is from ancient Mesopotamia, around 3,300-3,200 B.C.[4] Scribes recorded assets on clay tablets with proto-cuneiform symbols and markings representing the taxed items. Taxes were collected on livestock, for boating, and for many other activities and items.

During the earliest dynasties of China, tax was collected from the commoners who used farmland, since all the land belonged to the ruler.[5] Even if the crop failed or if the harvest was small, a part of it was still collected as tax. Poor farmers would suffer immensely when they could not produce enough harvest to feed their families, let alone give a portion to the rulers.

Taxation in the United States

In the United States, governments have collected taxes for different reasons over time. Taxation began in the colonies as early as 1634, and until independence in 1776, colonists were subject to taxes by both their local government and by Great Britain.[6] Let’s look at the most common types of tax records where you might find your ancestors.

Quitrents

Quitrents were taxes paid to the Crown. In English manorial society, “the land obligations due the manor, such as plowing and haying the lord’s land” were calculated as a yearly monetary payment, which would “quit” the person’s obligation once paid. [7] Many of the southern colonies collected quitrents, while the system did not exist in New England. The amount of tax was calculated based on the acreage of the land grant.[8]

Real Estate/Land Tax

Land has been taxed since the early days of the colonies. If your ancestor owned land, they were likely taxed on it. Real estate and land tax lists contain valuable information about the land your ancestor owned. It will include the number of acres and might include additional information about the quality of land, what kinds of crops are grown, the amount of harvest, and information about the buildings, livestock, and value of the farm. If your ancestor owned pieces of land in different counties, be sure to check for lists in each county, as your ancestor will be listed on both lists, even for the same year. Once you see that your ancestor owned land, it’s time to look for land records!

Personal Property Tax

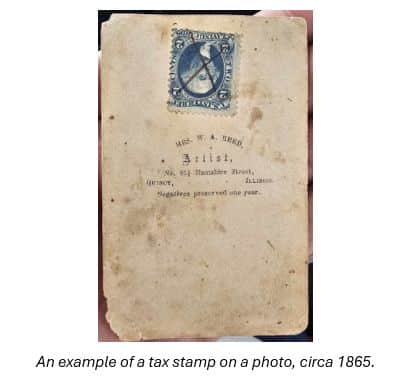

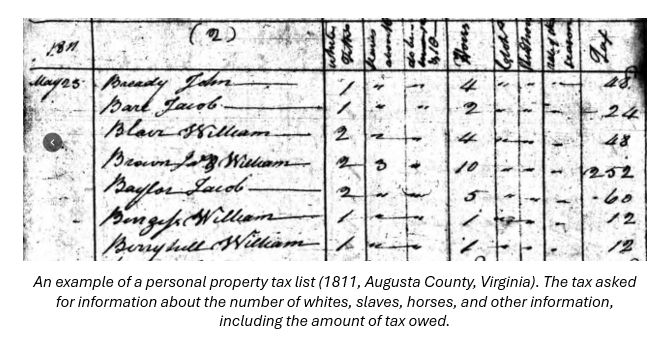

Personal property tax covered many different items that didn’t fall under land or houses. This kind of tax was imposed on various items, depending on the year and location. In 1782, Virginia implemented the personal property tax system to generate revenue. Beginning in 1815, luxury items such as musical instruments and furniture began being taxed to recover from the War of 1812. Enslaved persons are only recorded as numbers in the tax lists of their enslavers. Not until 1866 did men of color aged 21 and up appear by name in tax lists. During the Civil War, a tax on photographs was collected in the Union States from 1864 to 1866. The backs of photos taken during these years sometimes have a tax stamp, which is proof that the person paid the tax on the photograph.

Poll/Head Tax

Poll, head, or capitation taxes are all names for a tax that taxes a person rather than property or income. Enslaved individuals were also tithable, and the tax was due to be paid by the slave holder. Many early tithable lists no longer exist, but when found, they can pin your ancestor to a specific place and time in early colonial America.

Income Tax

The Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue was created by Congress in 1862. This was following President Lincoln’s establishment of a permanent internal tax system.[9] Tax assessment lists from 1862 until 1918 can be found on Ancestry.

An example of a personal property tax list (1811, Augusta County, Virginia). The tax asked for information about the number of whites, slaves, horses, and other information, including the amount of tax owed.

Why Genealogists Should Care About Tax Records

You might wonder, "How can a list of names and numbers help me break through my brick wall?” Tax records contain valuable information about a person's land, finances, and possessions. Typically, the further back in time you go with tax records, the less information was recorded in them. You may only find a list of names and a number in an early colonial list, and a pre-printed form with detailed information in a more recent record.

Filling in the Gaps

Tax records are great for filling in gaps between census years. Since taxes are taken yearly, locating your ancestors in a tax list is a yearly snapshot of them, instead of a snapshot every 10 years that the census provides. Anyone who has spent time engaged in 19th-century US research knows about the burned and nearly-total loss of the 1890 census. Tax records can help piece together the 20-year gap between 1880 and 1900.

Tracing Migration Routes

Locating your ancestors in tax lists throughout their lives can give you information about their migration routes, especially if they moved between census years. Even if they didn’t move to a different county, it can still be interesting to see where within the county or city they lived in each year.

Locating Your Ancestors’ Origins

If you are having trouble locating where your ancestor came from within the US before they arrived in a particular place, tax records can be extremely helpful in locating where they may have originated from. Tracing back those individuals who lived around your ancestor is another way to try to get back to a place of origin.

Learn About Your Ancestor’s Lifestyle

Analyzing your ancestors' valuations in their tax records can indicate their lifestyle and finances. Did they own items like a clock or a piano, or did they own gold or silver? These are some of the pieces of information you can learn from tax lists that can help draw a picture of your ancestor's life during that year.

FAN Club

Tax records are a great resource for finding members of your ancestors' FAN club – the friends, associates, and neighbors who may give additional clues about your ancestors. Although some lists were rewritten in alphabetical order, the most beneficial kinds of tax lists are those listed in non-alphabetical order. Some tax lists are listed by visitation order, district, or neighborhood, and will provide the names of your ancestor’s neighbors. It is always noteworthy if your ancestor is living near other people with his last name or the last name of family members (just be sure that the list isn’t in alphabetical order, as the provenance of the order of the names is lost). Use software like Excel, Airtable, or Word to record who appears around your ancestor in the tax lists.

Where to Find Historical Tax Records

FamilySearch Catalog

The FamilySearch catalog contains the most extensive collection of tax records online. Most images are viewable online, though there may be some collections you will have to view from the FamilySearch Library or a FamilySearch Library Affiliate. Drilling down to your area of interest (think about what jurisdiction was responsible for collecting taxes – in the US, it was typically the county or town) will show you a list of available tax records. You can also use the “images” tab and search a location there.

FamilySearch Full-Text Search

Released at RootsTech 2024, FamilySearch's new full-text feature revolutionizes how we access and find our ancestors in unindexed records. Millions of unindexed records are now fully searchable using artificial intelligence and handwriting reading technology—and not just by name. Remember that handwriting technology is not perfect. There will be occasional errors in the transcriptions, so you may have to get creative with spelling your ancestor's name. Think about how many ways you can spell a name, and how many ways AI handwriting might read it. Handwriting can be difficult to read, especially the further back in time you go, so think about how it could be misread.

Local Archives, Libraries, Societies, and Courthouses

If the location and time period you need do not have accessible records online, try contacting local facilities like archives, libraries, historical and genealogical societies, and courthouses. Some facilities that house tax records may not be accustomed to working with genealogists. You may have to research to see if the records exist and where they are held.

Tips and Pitfalls

Do a Surname Survey in a Particular Location

Looking through tax lists for a set of years in a specific place can help you gather names of other possible family members. This is especially helpful if you cannot find a father for your male ancestor. If you know where he was living at the time he was of taxable age, you may be able to get candidates for potential fathers based on who else is listed on the tax list during that time.

Being Aware of Individuals of the Same Name

Be sure to also check the jurisdictional history in your research location. For example, county and state borders changed frequently over time in the United States, so learning the history of a location is important when going back in time. If you are having trouble locating your ancestors in a list, search for them in a neighboring county and in the parent county (the county it was created from).

Pay attention to when someone first appears on a tax list and when they stop appearing. When someone appears in a new location, this indicates that they have just become of age to pay taxes or have recently moved to the area. When someone stops appearing, they could have died, moved, or become exempt from paying taxes due to their older age, veteran status, if they were poor, or many other reasons. Be sure to check the laws in the location and period you are researching to learn more about who was taxed and who was exempt from paying taxes.

Stay organized by using programs like Airtable, Excel, Google Sheets, or genealogy software to record your ancestors’ entries in tax lists. This is a great way to see their financial status over time, and it can help you identify when your ancestors bought and sold land.

Tax records of all kinds offer a wide variety of information about your ancestors' livelihoods. They are not just a list of names and numbers, but a snapshot of a specific time and place. As soon as you are done filing your own taxes, dig into the tax records of your ancestors.

And if you need help digging up those tax records for your ancestors, reach out to Price Genealogy. We can help!

Tyler

Image Sources

1 – Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich from Pexels: https://www.pexels.com/photo/tax-documents-on-black-table-6863259/

2 – Photo in the possession of the author.

3 – Augusta County, Virginia, Personal Property Tax Books, entry for John Bready, 1811, p. 2, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 16 April 2025); digital image 13 of 655.

Resources

FamilySearch Catalog – https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog

FamilySearch Images – https://www.familysearch.org/en/records/images

FamilySearch Full-Text Search – https://www.familysearch.org/search/full-text

United States Taxation - https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States_Taxation

Virginia Personal Property Tax Records, Ancestry – https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/62774/

IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918, Ancestry – https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1264

Sources

[1] “Income Tax Day,” Library of Congress (https://www.guides.loc.gov/this-month-in-business-history/april/tax-day), 2025.

[2]“Benjamin Franklin’s last great quote and the Constitution,” National Constitution Center (https://www.constitutioncenter.org/blog/benjamin-franklins-last-great-quote-and-the-constitution), 2023.

[3] “Taxes in the Ancient World,” University of Pennsylvania Almanac (https://www.almanac.upenn.edu/archive/v48/n28/AncientTaxes.html), v. 48, no. 28, 2 April 2002.

[4] Ponti, Crystal, “The World’s Earliest Evidence of Taxation,” History (https://www.history.com/articles/tax-artifacts), 2025.

[5] “Taxes in Ancient China. 1,33 BCE – 280 CE,” Digital Tax Technologies (https://www.taxtech.digital/2023/08/10/taxes-in-ancient-china-1300-bce-280-ce/), 2023.

[6] Jensen, Jens P., “Property Taxation in the United States,” (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1931); Internet Archive (https://www.archive.org/details/studiesineconomi0000unse_c4o2).

[7] “Virginia Taxation,” FamilySearch Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Virginia_Taxation).

[8] Carpenter, Joanne G., “Quitrents,” NCpedia (https://www.ncpedia.org/), 2006.

[9] “IRS History Timeline,” Internal Revenue Service (https://www.irs.gov/irs-history-timeline), 2015.