Overcoming Irish Brick Walls – Names

28

28Apr

“Stupid website, it always gives the wrong names. That’s not what I was looking for.” I have seen and heard those comments so often when people didn’t realise they had been given the right information but they just didn’t understand it. Admittedly, there should have been explanatory notes or they should have been displayed more prominently.

“Stupid website, it always gives the wrong names. That’s not what I was looking for.” I have seen and heard those comments so often when people didn’t realise they had been given the right information but they just didn’t understand it. Admittedly, there should have been explanatory notes or they should have been displayed more prominently.

Names in Ireland are not always what they seem. In fact, that is most of the time. One of the first things that one learns when doing genealogy in Ireland is the importance of variations, especially in spellings. Why? And why so many?

Many’s the time I have been told “they never spelt their name like that” or “they always had an E in it.” Forget it. The spelling is irrelevant. There was no set spelling for any name— forename, surname, or placename—until as recently as the 1920-30s. Few people got much schooling, and were not expected to have any, so they just gave their information and someone else wrote it down for them—presuming that they wouldn’t be able to read or write when many could if they had been allowed to. Whoever was writing everything down just spelt it as it sounded, and since accents could vary a lot even over the space of just a few miles, the spelling could be quite local. So, Brown and Browne are just the same, and the Smythes are no better than the Smiths, whatever they might have thought themselves. And the Smiths, most of them were just Gowans which is the Irish for a smith.

Mac or Mc are Irish as well as Scottish meaning “son” of “son of,” and O’ comes from Ua meaning grandson or descendant. These prefixed most Irish names but they were often dropped. Mul- comes from Maol, Irish for the tonsure that monks wore and as a prefix denotes a follower or servant. Ryan is one of the oldest surnames and was originally O’Mulryan. Fitz- comes from the French for a son. These names came from the Normans who were third generation Vikings who had settled in northern France (they had already come to Ireland) giving their name to Normandy, arriving in Ireland in 1169. The Fitzpatricks were the only Irish family to adopt the Fitz in spite of not having any Norman connection.

The Normans, who were the forerunners of the English, were not the only invaders and they brought Welsh and Flemish (Flemings) with them. They conquered the island of Britain and came to Ireland in several waves, followed by Scots in the Northern counties, Huguenots (French Protestants), Germans from the Rhineland (Palatines), Moravians from Moravia (now the Czech Republic), Italian craftsmen, and many others. They all brought their own names which were added to the mix of names to be found in Ireland and given a local twist like Shinkwin for Jennings.

The Normans, who were the forerunners of the English, were not the only invaders and they brought Welsh and Flemish (Flemings) with them. They conquered the island of Britain and came to Ireland in several waves, followed by Scots in the Northern counties, Huguenots (French Protestants), Germans from the Rhineland (Palatines), Moravians from Moravia (now the Czech Republic), Italian craftsmen, and many others. They all brought their own names which were added to the mix of names to be found in Ireland and given a local twist like Shinkwin for Jennings.

The Penal Laws in the 18th century banned the O’ and Mac, but this happened in written records not everyday speech. As the Penal Laws were relaxed towards the end of the century, O’ and Mac crept back in, especially with the rise of nationalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some names never dropped the Mac such as McGuire (also Maguire) and McGrath (Magrath). Other names became more common without the Mac like Wade for McQuaid although Wade can also be English.

In early parish records or those in areas that were mainly Irish-speaking, it may be possible to see names evolving from the original Irish to their modern form, as with Foley, from O Foghla [pron. O Fowloo] via O Fowlue and similar spellings, a robber or plunderer, or Broderick or Brothers from O Bruadar via Broder or Bruder. Bruadar was the Viking warrior who killed Brian Boru at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014 although some Brodericks may have been ap-Roderic of Welsh descent.

Researching my grandfather’s family in Co. Monaghan I could find nothing until I discovered that the Ls and Ns were interchangeable there, just as they were in East Galway, the Bristol area in England, and probably other places as well. Once I found that my McConnells were actually McConnon (different origins and unrelated) a whole new world opened up. Blundell and Blunden are also interchangeable as are Whelan and Phelan (O Faoláin pron. O Fwaylawn meaning a wolf), the only difference being local pronunciation which can also change Mullins to Mullane [pron. Mullaan], and Gilroy to Kilroy.

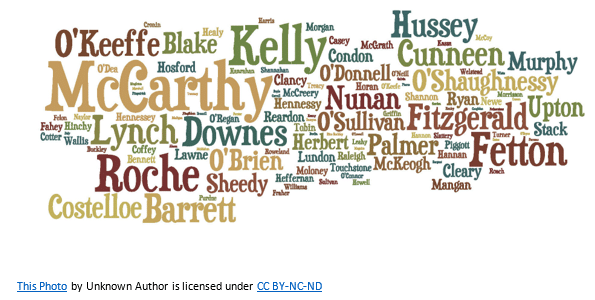

Names that are interchangeable are called synonyms and there are lots of them in Ireland, often names that are not related and have different origins but looked similar in the parish records. So you have Farr and Phair, Mangan, Manning and Mannion, and in certain areas Kelly having taken over minor names like Kealy and Queally and Kiely—with loads of variant spellings for each. Hurley can be Murrily or Herlihy, and McKenna can be Ginnaw, Gina [pron. Ginna] and Gna in Cork and Kerry, Cashman for Kissane, Clifford for Cournane. There are lots of others.

There are many other synonyms: Spain for Kavanagh (a branch of the family returned from exile in Spain); Silke for McNamara in the south-west because that family loved fine clothes although it is also found in East Galway where it is a substitute for Sheedy which comes from Síoda [pron. Shee-adda] meaning silk; Garde for Uniacke in East Cork, McGillicuddy and many others for O’Sullivan in Cork and Kerry. And there are very many others.

Some names are a nightmare with all the spelling variations, like McDonald / McDonnell / McDaniel all interchangeable with many variations. Searching parish records manually (always best if you have the time, energy and patience) watch for anything and everything that might be relevant. Using online indexes and databases, use wildcards if possible. Go through each variant individually and you will find many variations in each family.

Two websites that are very good for surname variations are www.irishgenealogy.ie (free) and www.rootsireland.ie (subscription) as the databases were compiled by local people familiar with the names, handwriting and variations. For church records, check to see what is available on both websites as they are complementary and do not overlap. Enter the parents’ surnames or just the father’s (the mother’s name might not have been recorded) and see all the variations that appear. If the parents’ names are correct, and for the right time frame and area, they are probably for the same family (depending on how many families of the same names were in the area). O’Leary can appear as Oleary in some indexes due to the handwriting being misinterpreted. There are other websites but you will probably find more on Irish Genealogy and Roots Ireland. One of the good things about Irish Genealogy, like the National Archives website (www.nationalarchives.ie), is that they accept wildcards so if they do not work the first time, try putting them in a different place in the name. And both are free to use. Irish Genealogy also includes civil records.

Many clerics never wrote anything in full if they could avoid it. Some names were abbreviated so often that the abbreviations became accepted as surnames themselves like Cuddy from Cuddihy, Hutch from Hutchinson and Pender and Prender from Prendergast.

Some English surnames in Ireland are so long established that it is a surprise to find they are not Irish. The Scottish name Cunningham replaces many local names in Co. Cork such as Cunniam and Cunnegan, Conaghan in Donegal and Derry, and Counihan in Kerry. Buckley (from the English Bulkley) has replaced Buhilly and Boughla and other similar names in Cork. Harris and Harrison replace Harrihy, Henry and Horohoe; Harrington O’Hingerdell and O’Harroughten especially on the Beara Peninsula in the south-west. In Kilkenny, Kirby replaces Kerwick and Kervick. And there are many others.

Byrne / O’Byrne, an Irish name, one of the most numerous names in Ireland and found everywhere, is often a substitute for Burns which is Scottish and Beirne which is of Norse (Viking) origin. Searching for such names on an Irish website it is not necessary to put in the O or Mc but on other websites each form of the name must be a separate search.

The name Clark (with or without an E) can be Irish, English, or French in origin often depending on where it is found. If it is of Irish origin, it is probably one of the oldest names in the country, coming from O Cléirigh and means a clerk in each of those languages.

Like most places, surnames in Ireland were derived from patronymics (O’Brien, the grandsons or descendants of king Brian Boru and McCormack, the sons of Cormac); nicknames (Durkan the pessimist); occupations (Lee from Mac an Leagha, the son of the physician—there are at least 12 different spellings of the name or Ward from Mac an Bhaird, the son of the Bard or poet;); but only a few from places (McNulty, Mac an Ultaigh, son of the Ulsterman). In Ireland, places were called after people rather than people being called after places.

If you can’t find a family in the 1901 or 1911 census, it could be because they filled out the forms in Irish. If you know where to look for them, you may still be able to identify them. For the names O’Connell or McConnell in Irish, type in C*onaill so that it will bring in both names as well as the female forms of the names which are different. Some families registered their births, deaths, and marriages in Irish in the 20th century making them harder to find.

Just to confuse you, the names Abraham (Judge), Cohen (Coyne) and Levy (Mountain) are all of Irish origin in Ireland not Jewish, and Keller is not German but a contraction of Kelleher, all with many variations. Doris is a surname, a variant of Doorish, not a girl’s name.

With so many variations of nearly every name you can think of, what is the best way to find them? Online indexes, www.irishgenealogy.ie (free) and www.rootsireland.ie (subscription)[1] are very good for variants and will probably come up with many that you would never even think of. On Irish Genealogy, you can use wildcards and you can also use them on the website of the National Archives of Ireland,[2] so play around, even putting them in different places to see what you can come up with. John Grenham’s website[3] (partly free) lets you search Roman Catholic church records by parish according to county, and provides lists of all possible spelling and surname variants found in the records, some due to misspelling and misinterpretation of the handwriting. Images of the records are also provided on this website. John also does a drily entertaining and useful blog on Irish records.

The best books on surnames are still those by Edward MacLysaght,[4] Patrick Woulfe[5] and Seán de Bhulbh.[6] MacLysaght’s books were written in the 1980s, Patrick Woulfe’s in 1923 and his nephew Sean de Bhulbh’s in 1997. When using Woulfe and de Bhulbh’s books, don’t be put off by the first half of their books being in Irish and the second part is in English; they list names with their prefix, all the O’s together and all the Mc’s together. All of them give variations and explain the origin of most names. MacLysaght’s books list names without the prefixes O’ and Mac, although they are also included, as in Connell, McConnell and O’Connell.

Think laterally, outside the box, and be flexible, very flexible.

Happy hunting.

At Price Genealogy we have a team of professional genealogists who conduct ancestry research in Ireland and around the world. We use the latest methods of family history research, including DNA genealogy. We are happy to help you learn more about your family’s heritage and ancestry.

By Rosaleen

[1] These two websites complement each other and do not overlap so check to see what they hold before using them.

[4] The Surnames of Ireland, Irish Families, More Irish Families

[5] Sloinnte Gael is Gall [Surnames Irish & Foreign]

[6] Sloinnte Uile Eireann [All Ireland Surnames]