Overcoming Irish Brick Walls – Finding Places

31

31Mar

Finding places in Ireland can be difficult, even when you think you know the names. There are several problems—administrative divisions, name changes, pronunciation. Never mind misremembering.

Finding places in Ireland can be difficult, even when you think you know the names. There are several problems—administrative divisions, name changes, pronunciation. Never mind misremembering.

Let’s start with administrative divisions. Without getting too technical, there are townlands, civil parishes, ecclesiastical parishes, baronies (now obsolete), counties, provinces, electoral divisions, registration districts and Poor Law Unions. The last three overlap and have different names for different purposes and appear mainly in civil and census records.

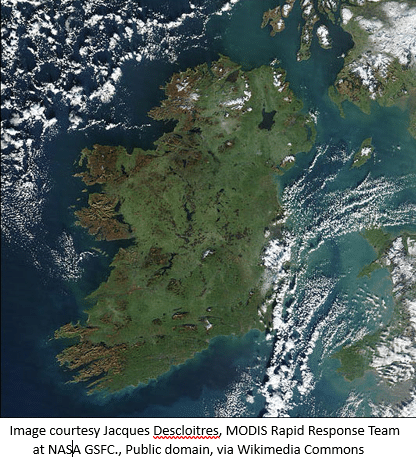

There are four provinces, Ulster, Leinster, Munster and Connacht, roughly north, east, south and west. There are 32 counties on the island of Ireland, 6 in Northern Ireland (part of the United Kingdom), the rest in the Republic of Ireland. Of the 9 counties in the province of Ulster, 6 are in Northern Ireland and the remaining 3 are with the South (the Republic). (The most northerly point in Ireland is in the South not the North! We do like to complicate things.)

Civil parishes are more or less the same as Church of Ireland parishes—though not always the same as Roman Catholic parishes, and they were the equivalent of the county council until 1899 when county councils were established. Any kind of parish can be split between two or more counties, even between the two political administrations. And the one placename can apply to a townland, parish, county and registration district or poor law union.

The smallest administrative unit is the townland which can vary from a quarter of an acre (in a town or city) to several thousand on the side of a mountain. The smaller the townland, the better quality the land, and the bigger it is the poorer the land. Very often, regardless of the number of roads in a townland, the only address will be the name of the townland even today. If you are looking for a townland or the people who lived in it, it helps to know the parish (civil or religious), barony, county or registration district but it’s not essential. That will come later. Townlands can be split between parishes and counties and registration districts. And when you start to search land records, they are always arranged by civil parish.

When looking for a townland, forget road maps, you need the ordnance survey map or www.logainm.ie, which will give alternative spellings, as well as maps and meanings of names and early forms, found under “More” and “Archives,” although some of the notes may be in Irish. Despite the name, the townland is strictly a rural entity, but may not have any houses, and should not to be confused with a township—there aren’t any townships in Ireland.

If people are trying to remember where they or someone else in the family lived many years ago, they might be vague about the name or get names mixed up. The pronunciation could get distorted, never mind the spelling which may confuse others later. Spelling and pronunciation can both change. Spelling is often simplified and pronunciation can be gentrified. When I was growing up, I had friends living a few miles away in Kinsalebeg, which was then pronounced Kin-salla-beg with four syllables. It is now pronounced Kinsale-beg with just three syllables, like the town of Kinsale about 40 miles away. Trying to find it by spelling it phonetically the old way would be very difficult.

Irish spelling and pronunciation can seem difficult to those not familiar with it. Usually, if a consonant is followed by an H, the H silences or changes the sound of the consonant. Drogheda is Droh’-hidda (unless you are a local and then it is Dthrawduh), and Cobh is Cove. (There are a few exceptions but we won’t go into them.) Names finishing in -ane are pronounced -aan, but Naas is Nase like mace.

Duplication of names is another problem. There are 33 places called Crumlin scattered around the country. The name means a crooked glen. There are 26 places called Dundrum. Dundrum means the fort on the ridge. As for names beginning with Bally- or Ballin-, there are thousands. Bally means a town or homestead. Ballynoe just means Newtown and there are 40 of them, nearly half of them in Co. Cork; Shanbally is old town, with only 27 of them. Ballybeg is the little town and Ballymore the big town.

In Ireland, places are called after people, while in other countries, people are called after places. Sometimes places have two names, one in English and another an approximation of the original Irish, the two usually unrelated to each other. Names like Newtown don’t bear thinking about because there are so many, and if a name begins with Castle- you need to know which castle or you have no hope. In your search, you may find who the town or castle was called after.

I had a case where one branch of the family was from Millstreet in North Cork but they thought that the other side of the family was from the North (meaning Northern Ireland). I eventually proved that they were from Newmarket, a town 15 miles north of Millstreet, not 250 miles north at the other end of the country. So North was relative in that case.

Another problem can be working out which county a family came from, especially if they give different information in the 1901 and 1911 censuses (the only two censuses currently available in Ireland,[1] although the 1926 census is due to be released in 2027). In one census they might say that they were born in Mayo and in the other they might say that they were born in Galway. When these are adjoining counties, as Galway and Mayo are, it usually means that the family lived on the border of the two and moved frequently as people did then. It might seem strange that people didn’t know which county they lived in but the county meant little to people at that stage. It was the parish that mattered. It was only with the rise of the GAA (the Gaelic Athletic Association, founded in 1884 to promote Gaelic culture and games such as Gaelic football or hurling) and county games that people began to identify with their county.

When people emigrated, if they were asked where they were from, they would usually give the name of the nearest large town as it would be better known than their townland. So, if they said that they were from Bray, they might not have been from the town of Bray but from outside the town, maybe several miles away. If they said that they were from Cork or Galway, that is more complicated as that could mean either the city or the county. But it is still a starting point. Church records are arranged by parish and diocese, not town or county.

Very often a couple who married were from different parts of the country. Then one has to think how and where they would have met. Due to the distance involved, it might be very unlikely that they could have met in Ireland, and one needs to look elsewhere for the marriage, maybe in England or Scotland before they emigrated to America, Canada or elsewhere. Unfortunately, when that happens, one doesn’t get any Irish placenames. But it is important to remember that the Irish never emigrated in isolation but always with others or went to others who were always related or from the same parish. This is also known as chain migration. Because of this networking, a good place to start is The Search for Missing Friends (immigrants’ advertisements in the Boston Pilot from 1831 to 1860, published by the New England Historic Genealogical Society and is searchable on Ancestry). Researching the friends and neighbours of your ancestors can lead back to your own family.

If you have managed to identify the townland—congratulations! There are two good websites you can use for more information. A goldmine of information about civil parishes (search by county) is found at www.johngrenham.com (partly free). It lists all townlands in the parish, and all available records for each, and provides maps for civil parishes, Roman Catholic parishes, and Poor Law Unions (Registration Districts). John also does a very entertaining and useful blog on Irish records.

The Ordnance Survey website is www.osi.ie. Scroll down to Map Viewer, then after selecting an area on the map of Ireland, click GeoHive Map Viewer, and the icon for Basemap Gallery (top left) to access old and modern maps, as well as aerial views. If you want the ground view you will have to use Google Maps.

Although there have been many works on the subject published more recently, one of the best works on Irish placenames remains Patrick Weston Joyce’s Irish Local Names Explained, first published in 1884. A facsimile of the 1923 edition was published in 1996,[2] a small book with a vocabulary of Irish root words found after the placenames at the back. It’s still my go-to source for meanings and locations, although many names have been simplified (in both Irish and English) since it was originally published. Occasionally, places with an English name have had a plebiscite to restore the original Irish name such as Dingle in Co. Kerry (near where Star Wars was filmed), now called Daingean [pron. Dangin], another word for a fortress.

At Price Genealogy we have a team of professional genealogists who conduct ancestry research in Ireland and around the world. We use the latest methods of family history research, including DNA genealogy. We are happy to help you learn more about your family’s heritage and ancestry.

By Rosaleen

[1] Apart from a few “fragments,” the only two censuses available are those for 1901 and 1911. Those for 1821 to 1851 were lost in the destruction of the Four Courts complex, which then housed the Public Record Office, during the Civil War in 1922. Those for 1861 to 1891 were pulped to recycle paper during World War 1 without realising that the information they contained had not been abstracted as it was in the rest of Britain.

[2] ISBN 0713465182