Norwegian Research – Part 2

9

9Oct

The first blog post on Norwegian research introduced some of the most useful records for Norwegian research. Have you successfully found your ancestors in any of them? If not, you may be facing one of the two common Norwegian genealogy research problems discussed below.

Norwegian Genealogy Part 2

Immigration/Finding the hometown

After immigrating, many Norwegians chose not to talk about their home country. They stopped speaking the language, they stopped participating in Norwegian traditions, and they did not pass on information about where they came from. Even if this is the case, all is not lost. There are many great resources for tracking down a Norwegian immigrant ancestor’s place of origin.

Citizenship in America

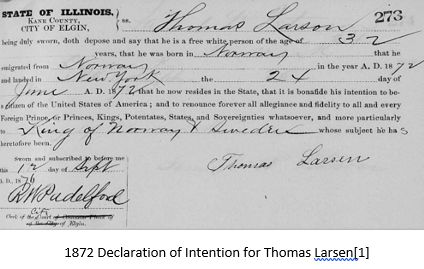

Once an immigrant settled in America, the next step for many was to become a citizen. The records associated with this process are called naturalization records. After arriving, the individual had to declare their intent to become a citizen; then, typically two to three years later, they could officially petition the government for citizenship. Before the Naturalization Act of 1906, less information was provided in the documents. It would contain their name, maybe their age, and the country to which they were renouncing their allegiance. These documents can still be valuable, however, because every so often they contain extra information. The example below shows the day that the immigrant landed in America.

After 1906, the individual had to provide much more information about themselves throughout the process. They would give detailed information about the ship that they arrived on, their close relations such as spouse and children, where they were from in their home country, and when they were born. Ancestry and FamilySearch have digitized a lot of these naturalization documents. On the FamilySearch wiki, there is an article about naturalization that can help you navigate to the right records.

See the article “United States Naturalization and Citizenship”

Traveling on the Ship

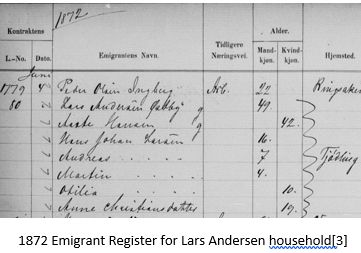

Beginning in the late 1860s, when a Norwegian decided to emigrate from the country, they had to find a shipping company agent and sign a contract to get a ticket. The local police verified the contract and then the emigrant could travel. The local police and some of the companies kept registers of these emigrants.[2] When the traveler finally arrived in a North American port, they were listed on the ship’s passenger records. When used together, these two sources can be invaluable for tracking an immigrant’s journey and finding their place of origin.

Ancestry and Digitalarkivet have some great tools for finding these records:

Indexed Passenger Lists:

Arrival to New York: “New York, Passenger and Crew Lists…, 1820-1957”

Arrival to Canada: “Canadian Passenger Lists, 1865-1935”

Indexed Emigrant Registers:

Police: “Emigrants from Oslo 1867-1930”

Police: “Bergen Police district,…: Emigrants via Bergen 1874-1930”

See all indexed police emigrant registers here

Scanned Collections:

White Star Line: Kristiania(Oslo) Office, Emigrant Protocols, nos. 1-5: 1883-1923

See all scanned police emigrant registers here

The partial image below shows Lars Andersen Østby and his family on the Oslo police emigrant registers. The register recorded the date of the contract, their name, their age, where they were from, what ship they were taking, and more.

No Farm Books for my Family

While farm books or bygdebøker are helpful shortcuts information on a family, they are based on sources and records that are available to the public. Authors of the farm book spend thousands of hours going through the church, probate, land, and tax records for every family in one area. It is not too difficult to find these records for one specific family, especially because most of these records are available through Digitalarkivet. Church records were already discussed in part one of this blog on Norwegian genealogy research.

Probate Records

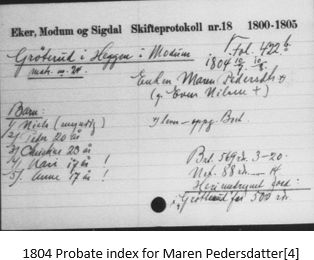

The most helpful records for extending ancestry past the 1800s are the probate registers or skifteprotokoller. They were kept by the judicial district or sorenskriveri. When an individual passed away, their property had to be passed on to somebody else. Unfortunately, not every transfer of property was documented. However, if it was documented and the probate exists, the documents accompanying the process often provide valuable information on the surviving relatives such as residence, age, and marriage. Sometimes, an index or skiftekort was created to accompany the probate records. The indexes are organized by location and can lead to the original documents. They often provide a summary of the information on the original documents. In the example below, the index lists the farm in the top left and the date and location of the original in the top right. The deceased person is listed beneath the date and has the cross next to them. The surviving relatives are listed on the left side.

Land and Tax Records

Land books or pantebøker and tax records or regnskap/skatt can also be useful after exhausting the probate records. Land books were kept by the judicial district or sorenskriveri and many of the tax records were kept by the bailiff’s district or fogderi. They typically contain far less genealogical information but go further back in time and can be useful when land stayed in the family.

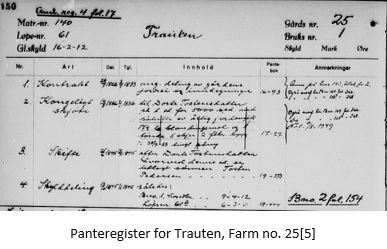

The example below is the panteregister or land registry for a farm in Nord-Odal parish. This index lists every transaction that occurred on the farm beginning in 1830 and going forward. Older indexes exist, but there is a lot of variety in how these indexes are organized over time.

Various taxes were collected by the local bailiff. Most of the time the bailiff simply recorded an amount, a place, and a name. However, this can be helpful when few other records exist.

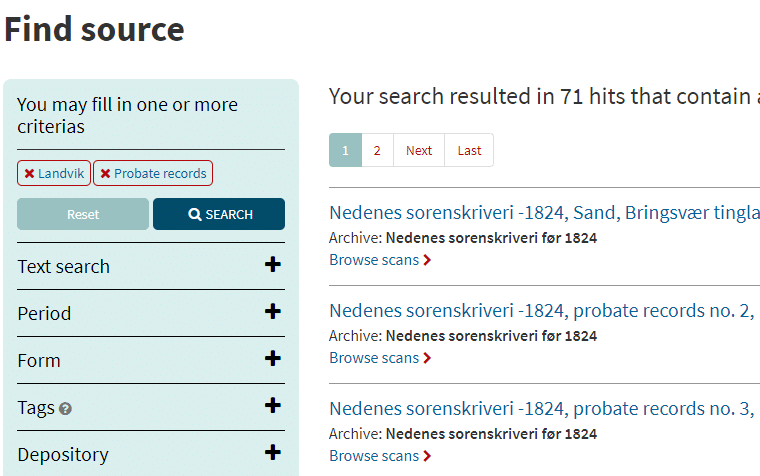

If you know the parish in which your ancestors lived, finding the probate, land, and tax record collections is fairly easy. Digitalarkivet’s find source tool allows one to locate probate records, land records, etc. for a specific parish. Then the records can be browsed for information on a specific family.

See the find source tool: https://www.digitalarkivet.no/en/search/sources

Conclusion

If you are having trouble extending your Norwegian genealogy, try out these record types based on the type of problem you are having. If it is a place of origin problem, look at the immigration and emigration records. If the problem is extending the Norwegian lines as far as they will go use the more advanced probate, land, and tax records to aid in your search.

As always, our researchers at Price can help at any point along the research path. We can help you extend your Norwegian family history as far as it will go.

-Forrest

[1] Elgin, Cook, Illinois, Naturalization records, images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS97-P9JG-4?i=349&cc=1989159 : accessed 8 October 2020), Thomas Larsen; citing “Elgin City Court Declarations, 30 Oct 1858-21 Nov 1882,” Book 2, p. 273; FHL Microfilm 1481624.

[2] Børge Solem, “Agent's authorization,” Norway Heritage, 2000-2006, http://www.norwayheritage.com/articles/templates/historic_documents.asp?articleid=26&zoneid=18.

[3] Oslo politidistrikt, Emigrantprotokoll, 1871-1876, images, Digitalarkivet (https://www.digitalarkivet.no/em20110222620704 : accessed 8 October 2020), Lars Andersen household, p. 113; Archive reference SAO/A-10085/E/Ee/Eef/L0005.

[4] Eiker, Modum og Sigdal sorenskriveri, skiftekort, 1676-1828, images, Digitalarkivet (https://www.digitalarkivet.no/sk20100224631611 : accessed 8 October 2020), index card for Maren Pedersdatter, p. 1609; Archive reference SAKO/A-123/H.

[5] Vinger og Odal sorenskriveri, Panteregister nr. 3.4, 1935, images, Digitalarkivet (https://www.digitalarkivet.no/tl20071106370859 : accessed 8 October 2020), Trauten Farm no. 25, p. 150; Archive reference SAH/TING-022/H/Ha/Hac/Hacb/L0004.

Do you have any Norwegian genealogy work that you're doing? Let us know in a comment below!