Native American Ancestry: Tips and Resources, Part 2

30

30Nov

Part two of this series discusses two specialized topics: Native American Indians in the military, and the use of DNA for Native American ancestry determination.

U.S. Military Involvement

Many Americans remain unaware of the major contributions Native Americans have made to the United States Armed Forces. American Indians served in every United States war from the Revolutionary War to the present day. They even served on both sides of the Civil War.[1] Their courage, determination, and fighting spirit were recognized by American military leaders as early as the 18th century. They had a reputation of serving with distinction and some received the Medal of Honor.[2]

It is estimated that more than 12,000 American Indians served in the United States military in World War I. Approximately 600 Oklahoma Indians, mostly Chotaw and Cherokee, were assigned to the 142nd Infantry of the 36th Texas-Oklahoma National Guard Division. The 142nd saw action in France and its soldiers were widely recognized for their contributions in battle. Four men from this unit were awarded the Croix de Guerre, while others received the Church War Cross for gallantry.[3]

Several federal offices have historically kept Indian records, including the departments of War, Interior, State, and since 1947, the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Prior to 1947, was the Office of Indian Affairs.[4]

If you are researching a Native American ancestor, be sure to not overlook military records. Let’s take a look at a few types of Military records available and where to find them. They are service records, court case files, headstone records, and pension records.

Service records

Service Records may show when, where, and by whom a soldier was enlisted; period of enlistment; place of birth; age at time of enlistment; physical description; and possibly additional remarks such as discharge information, including date and place of discharge, rank at the time, and if the scout, or soldier, died in service.

Available with a subscription:

Compiled Military Service Records of Maj. McIntosh's Company of Creek Indians in the War of 1812

World War II Army Enlistment Records

Indian Wars Service Record Index

Cards Concerning Revolutionary War Service and Imprisonment

Applications for Enrollment and Allotment of Washington Indians, 1911-1919

Compiled Service Records of Confederate Generals and Staff Officers, and Nonregimental Enlisted Men

Consolidated Lists of Civil War Draft Registrations, 1863-1865

Available for Free:

Frost’s Pictorial History of Indian Wars and Captivities

Native Americans in the Revolutionary War

Indian Wars of Carolina – Previous to the Revolution

Medal of Honor Records

Several Indian Scouts received the Medal of Honor, the list of which is provided by the United States Army Center of Military History. It covers the Indian War, World War II and the Korean War.

Available for Free:

US Army Center of Military History

Headstone Records

Headstones were provided by the government to Native Americans who served as enlisted Indian Scouts and to those who served in the Regular Army Indian Companies.

Available with a subscription:

Card Records of Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, ca. 1879 - ca. 1903

Applications for Headstones for U.S. Military Veterans, 1925-1941

Indian Bounty Land Warrant Records

Warrants usually contain the following information: date of issuance, name and rank of veteran, state from which enlisted, name of heir or assignee (if applicable). It should be noted that warrants issued at this time were assignable and were often sold by the veteran on the open market. When this was done, a notation on the reverse of the warrant indicates subsequent transfers of ownership from the veteran to heirs or assignees.[5]

Available with a subscription:

US War Bounty Land Records 1789-1858

Bounty Land Warrant Applications

Available for Free:

Pension Files

Pension files are an excellent source of information on Indian Scouts, not only about the scout, but also about his family and others with whom he may have served or who knew him or his wife. Indian Scouts and their widows became eligible for pensions with the passage of an act on March 4, 1917, relating to Indian wars from 1859 to 1891.

Available with a subscription:

Index to Indian Wars Pension Files, 1892-1926

Index to Selected Final [Pension] Payment Vouchers, 1818-64

Available for Free:

Civil War Pension Index: General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934

Index of Indian War Pension Files, 1892-1926

For more information on Indian Scouts, Indian Companies and Code Talkers, please visit the National Archives.

DNA Testing

For some folks, researching their Native American family has been difficult. In traditional research, the next step is generally genetic testing. Genetic testing, otherwise known as DNA, has been gaining popularity in genealogical research.

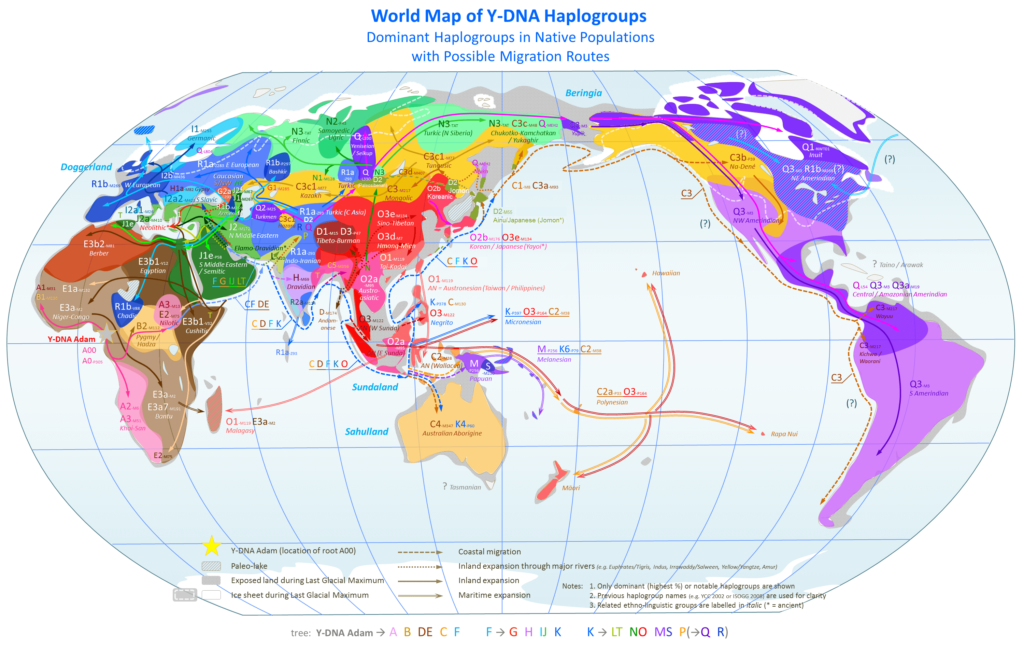

DNA is your genetic code. It determines traits from eye color to aspects of our personalities. This type of testing is becoming more of a discussion topic in Native American Communities.[6] However, using DNA testing to “prove” Native American Heritage has limitations. For several years, the most popular genetic ancestry testing services only categorized Native American ancestry into one broadly north, central, and south American region. Ground was broken in March 2017 when Ancestry.com’s DNA service added “Genetic Communities” to their ethnicity estimate service. These communities have since proven to at least accurately pinpoint regions in Mexico, and even specific Mexican states, where those of Mexican descent have ancestry. Overall, Native American DNA continues to be lumped into a broadly Native American category for both continents.

Many Caucasian and African American Americans take DNA tests with the hope to validate a long-cherished family rumor of Native American ancestry. It is generally believed among genealogists that the failure of such a test to recognize any Native American ancestry disproves such a family rumor. Unfortunately, one cannot rely on ethnicity estimates completely for proof of any ethnic origin. Genetic genealogist Roberta Estes explains in her blog DNAeXplained that due to the way DNA is passed from generation to generation, a Native American ancestor—even one who was 100% Native American at 5, 6, or 7 generations back may not appear at all on your ethnicity estimate percentages.[7] It logically follows, for example, that perhaps an ancestor who was half Native American at 4 generations back would still possibly not show Native American DNA in their ethnicity estimate. The problem is further complicated in that very few samples from the American Native population exist in the current databases being used for DNA tests. In addition, Kim TallBear, an anthropologist at the University of Texas in Austin, and a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, part of the Santee Dakota people in South Dakota, explains that a person with Native American ancestry may not show up on a genetic test as Native American, or may be told they are of East Asian or other descent. She even says that “there is no DNA test to “prove” you are Native American.”[8]

Being Native American is a question of politics and culture, not biology: one is Native American if one is recognized by a tribe as being a member. And one is not necessarily a member of a tribe simply because one has Native American ancestors. Another problem is that genetic analysis, and some of the processes involved, can be problematic for indigenous people in terms of their own cultural knowledge. Put simply, there are things involved in genetic analysis that some indigenous cultures consider violations of their principles or values.[9]

Tribes do not differ from one another in ways that genetics can detect. There is a widespread belief that genetics can help determine specific tribal affinities of either living or ancient people. This is simply false. Neighboring tribes have long-standing, complex relationships involving intermarriage, raiding, adoption, splitting, and joining. These social-historical forces insure that there cannot be any clear-cut genetic variants differentiating all the members of one tribe from those of nearby tribes. At most, slight differences in the proportions of certain genetic variations are identifiable in each group, but those do not permit specific individuals to be assigned to particular groups.[10] In conclusion, the best way to determine your Native American ancestry is to use the traditional genealogical methods, and records, to locate the tribes your family belongs to and then contact the tribe directly.

Billie and Mike

[1] Wikipedia contributors, "Native Americans in the American Civil War," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Native_Americans_in_the_American_Civil_War&oldid=865094552 (accessed November 16, 2018).

[2] FamilySearch Wiki contributors, "American Indian Genealogy," FamilySearch Wiki, (http://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/index.php?title=American_Indian_Genealogy&oldid=3251906 : accessed 16 November 2018).

[3] Naval History and Heritage Command, “20th Century Warriors: Native American Participation in the United States Military,” U.S. Navy, (https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/t/american-indians-us-military.html : accessed 16 November 2018)

[4] FamilySearch Wiki contributors, "American Indian Genealogy," FamilySearch Wiki, (http://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/index.php?title=American_Indian_Genealogy&oldid=3251906 : accessed 16 November 2018).

[5] Ancestry.com. U.S. War Bounty Land Warrants, 1789-1858 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

[6] American Indian and Alaska Native Genetics Resource Center, “Tribal Enrollment and Genetic Testing”, National Congress of American Indians, (http://genetics.ncai.org/tribal-enrollment-and-genetic-testing.cfm : Accessed 16 November 2018)

[7] Roberta Estes, “Ancestral DNA Percentages – How Much of Them is in You?,” DNAeXplained (https://dna-explained.com/2017/06/27/ancestral-dna-percentages-how-much-of-them-is-in-you/ : Accessed 16 November 2018).

[8] Geddes, Linda, “There’s No DNA Test to “Prove” your Native American”, NewScientist.com, Magazine Issue 2955, 8 February 2014, (https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22129554-400-there-is-no-dna-test-to-prove-youre-native-american/ : Accessed 16 November 2018)

[9] Brett Lee Shelton, J.D. and Jonathan Marks, PhD., “Genetic Markers Not a Valid Test of Native Identity”, CRG, Council for Responsible Genetics (http://www.councilforresponsiblegenetics.org/ViewPage.aspx?pageId=163 : Accessed 16 November 2018)

[10] Brett Lee Shelton, J.D. and Jonathan Marks, PhD., “Genetic Markers Not a Valid Test of Native Identity”, CRG, Council for Responsible Genetics (http://www.councilforresponsiblegenetics.org/ViewPage.aspx?pageId=163 : Accessed 16 November 2018)