Metes and Bounds and Township and Range: American Land Records Part I: Land Platting

1

1Nov

Part I of this two-part series is adapted from a lecture given by the author at the 2019 Brigham Young University Conference on Family History and Genealogy.

Land records are an incredibly important resource when doing genealogy research in the United States. These records do more than simply record where an ancestor lived or what property they owned, they can be a wealth of information about relationships, economic status, and much more! Like any other record type, it is crucial to utilize every aspect of land records. This goes beyond just reading through the deed and recording names– you need to get land platting!

What is Land Platting?

Land Platting is defined as drawing out the boundary description of a piece of property as given in a land record, usually a land deed. Platting refers to land described using the Metes and Bounds (measures and boundaries) system. Alternately, land graphing refers to land described using the Township and Range (or Rectangular Survey) system. Part II of this Land Records series will focus on land graphing, so keep an eye out for that post.

I do need to state here that though a land deed is generally described using either the Metes and Bounds method or the Rectangular Survey method, I have come across deeds that are a combination of both. So, when stated in this post that one method includes x while the other includes y, know that in genealogy, there can be no absolutes! If you use this information as a general guide, you will be better prepared to handle an anomaly when (not if) you come across one.

State Land States vs. Federal Land States

Before getting into the ins-and-outs of how to plat land records, it is important to understand where the Metes and Bounds land survey system was used. Metes and Bounds was used in what are now called the “State Land States.” This group consists of the original 13 colonies, states created from those colonies, Hawai’i, and Texas:

- Connecticut (CT)

- Delaware (DE)

- Georgia (GA)

- Hawai’i (HI)

- Kentucky (KY)

- Maine (ME)

- Maryland (MD)

- Massachusetts (MA)

- New Hampshire (NH)

- New Jersey (NJ)

- New York (NY)

- North Carolina (NC)

- Pennsylvania (PA)

- Rhode Island (RI)

- South Carolina (SC)

- Tennessee (TN)

- Texas (TX)

- Vermont (VT)

- Virginia (VA)

- West Virginia (WV)

Because these states had an established land survey system when the Federal Government was formed, they were granted the right to retain their land after ceding it to the government. As a result, they were in charge of granting/selling their own land and the Metes and Bounds system stuck. When you are doing research in land records of these states, be prepared for some land platting.

The rest of the United States was acquired through various means after the formation of the Federal Government, and the land became public domain. These states (every state except those listed above), referred to collectively as the “Federal Land States,” generally use the Rectangular Survey system. In the next post of this series, we’ll talk through graphing land descriptions in these states.

Value of Land Platting

As mentioned previously, land records can be a treasure trove of information. Land platting is sometimes overlooked, but it shouldn’t be! Here are a few examples of some ways that land platting can be very valuable to your genealogy research:

- Track land ownership to gain clues about relationships: Land platting is an excellent way to visually track land exchanging hands. If you plat your ancestor’s land and then plat a deed showing them selling half of their land to someone you don’t know of, you should check into possible relationships.

- Distinguish between same-name individuals in the same area: If you find multiple deeds showing multiple William Smiths buying land in Lancaster County, platting those deeds can greatly help you distinguish between the two (or three, or four…) men.

- Family members often lived close: If you plat multiple deeds created by individuals with the same surname, you may find that they lived quite near to each other. This could be evidence of relationships.

- Neighbors are often mentioned in deeds: Often a deed includes neighbors names in boundary descriptions (e.g. running south along John Brown’s eastern line). Platting the neighbors land as well allows you to piece together the neighborhood and create a FAN (Friends, Associates, and Neighbors) network for your ancestor.

- Determine the size, shape, and location of the land, as well as learn what resources it was near: If your ancestor owned land near valuable resources in the area, that may give you a clue as to their economic status or way of life. Equally so if they appear to have owned land far away from water or wood sources.

- Track changes in land division, which may be indicative of relationships or changing economic status: This is similar to the first point. Visually tracking the purchase or sale of land through platting can clue you into relationships (who is getting the large chunk of this ancestor’s property?) as well as changing economic status (are they consistently selling off smaller portions of their property?).

Metes and Bounds Terminology

Learning the terminology associated with Metes and Bounds land surveys is helpful to 1) identify whether or not your deed can be platted, and 2) understand how to plat the deed on your own. You will know your deed is surveyed in Metes and Bounds when you see the words chain, link, rod, and/or pole. You will notice phrases such as “South 45° West” and geographical landmarks such as “the oak tree by the stream” or “a stake and stones.”

If you see phrases including halves, quarters, sections, townships, and ranges, your deed is not Metes and Bounds, it is Rectangular Survey. It is important to remember, however, that the term township was also used to indicate a small geographic area within a county. Your Metes and Bounds deed may say someone owned land in Washington Township of Beaufort County, but you likely won’t find a phrase similar to “Township 3 West” in a Metes and Bounds deed.

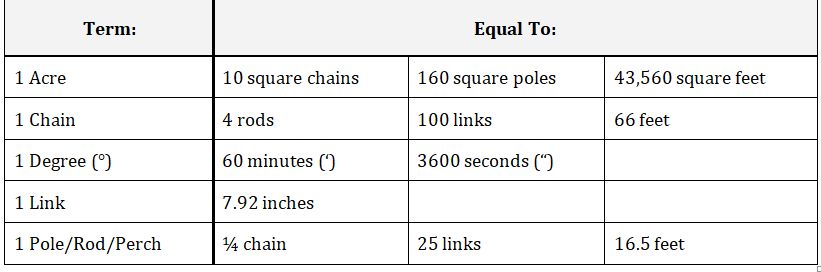

The following chart illustrates some of the equivalents for the various measurement terms used in a Metes and Bounds deed. It is important to know these equivalents for times when your deed includes phrases such as “56 chains and 25 links” or “north 80 degrees and 20 minutes west.” Understanding the ratios between the units is important for consistency.

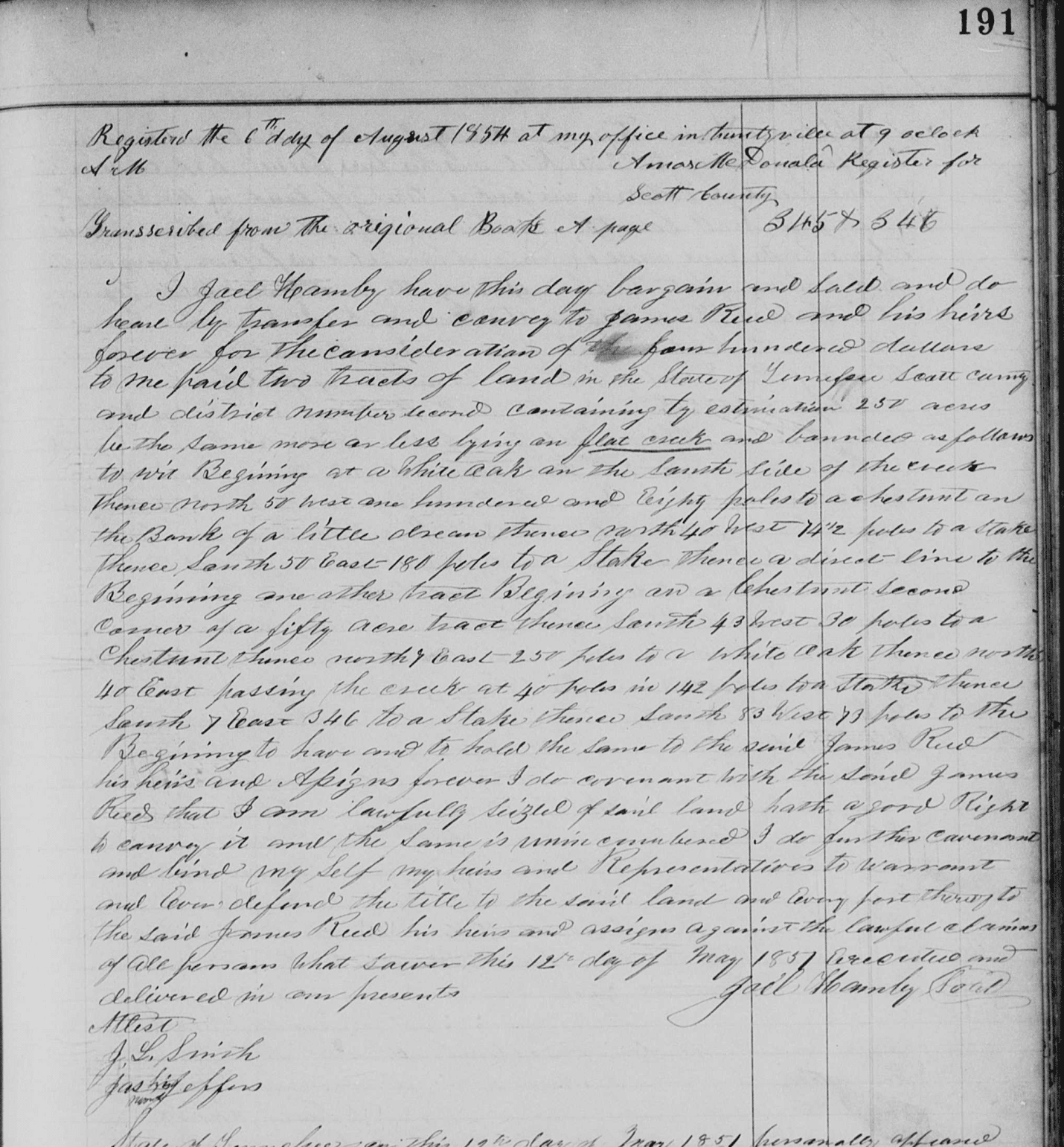

Now that we’ve laid down some of the basics of Metes and Bounds survey, where it was used and how to recognize its value, let’s get into some how-to’s of land platting! The deed[1] used in the example can be found on FamilySearch at this link: https://bit.ly/2IeLUHk. The slides walk you through one of the descriptions in the deed on page 191, but you can use the second one for practice!

Land Platting Step-by-Step:

Land Platting Steps:

- Read through your land deed and locate where the description begins. Often, you will find a phrase similar to “bounded as follows:” followed by “beginning at…”

- On a separate piece of paper or word document (not required, but very helpful), transcribe the description. Place each measurement description on its own line (e.g. N38°W 45 rods, or North 38° West 45 rods), and place each corner description on its own line as well (e.g. “...to a stake and stones,” or “...to the large pine on John William’s southern line”).

- Determine which is the primary length measurement in your deed. Usually, a description uses mainly rods, poles, or chains. Assign 1 millimeter = 1 primary unit, and be wary of measurement changes while platting.

- Mark a dot for your starting point on your graph paper. Begin in the center of the paper until you gain more experience and can sense where the description will go.

- Draw a basic compass rose on the paper (North on top), and a key indicating which measurement = 1 millimeter.

- Read through your first direction (let’s use North 38° West 45 rods as our example).

- If the first direction is North or South, the flat edge of your protractor will be vertical. If East or West, it will be horizontal.

- If the second direction is North, the curve of the protractor will be on the top. If South, on the bottom; if East, on the right; if West, on the left.

- Beginning at your first dot, place your protractor in the correct position (for our example, vertical with the curve on the left). The first direction will indicate which end of the protractor you will measure the degrees from (e.g. N = top, S = bottom, E = right, W = left).

- From there, move the number of degrees indicated towards the center of the protractor from the correct end. Mark a dot at that point. For our example, I would move to the left, following the curve, and mark a dot at 38°.

- Remove the protractor, and draw a line from your starting dot in the direction of your second dot the length indicated in the deed. Do not just connect the dots!! Following the example, I would draw a line 45 millimeters (for 45 rods).

- Cross off the directions for the line you just drew (e.g. North 38° West 45 rods) from your transcription so that you know you have completed that instruction.

- Erase the guide dot from the previous measurement, and create a dot at the end of the line you drew. Label the end of the line with the corner instruction from your transcription that immediately follows that line (e.g. a stake and stones).

- Continue from that point with the next direction, and continue through the end of the land description. DO NOT ROTATE YOUR GRAPH PAPER; keep North at the top.

Some tips to remember while platting:

- Round up or down any fractions of degrees or lengths that are too small to distinguish in the smaller scale.

- Label ALL CORNERS AND LINES at the end with all information in the deed.

- If you reach a point where the deed is not descriptive enough (e.g. continue southerly along the river bank) RETURN to the beginning dot, drop to the FINAL INSTRUCTION, REVERSE the cardinal directions (N38°W 45 rods = S38°E 45 rods), and work backwards until you can draw the “southerly” line.

The researchers at Price Genealogy are experienced with land documents and land platting and can help you use them to discover critical relationships. Many clues come from these records. Not only do they help build family trees, but land platting will help you understand the world in which your ancestors lived by visually seeing the lay-out of the land and by identifying the neighbors.

Amy

[1] “Deeds, 1850-1885; index to deed and mortgage records, 1850-1915,” Scott County, Tennessee, Register of Deeds, vol. A, pg. 191, Family History Library microfilm 926296, viewed digitally, http://familysearch.org, accessed June 2019.