Memorial Day—Lest We Forget

22

22May

With Memorial Day weekend upon us, may we remember the sacrifices made by those who paid the ultimate price so that we could live in a land of liberty. We appreciate our family members and ancestors who fought for and built up this country. Since many of us cannot name our great-grandparents, it is likely that our great-grandchildren won’t remember our names, unless we do something about it. Memorial Day is a great time to take steps to ensure that a worthy remembrance of our generation and of our ancestors shall not fade into oblivion.

Memorial Day Genealogy

On this day, we have the opportunity to remind ourselves of the intense devotions of those who died for us. It wasn’t until after World War II that Memorial Day was generally called Decoration Day. Putting flowers on graves of deceased family and soldiers was a common practice in the United States, well before the time of organized commemorations that developed during and following the Civil War of the 1860s. The experience of the horrific loss of life during this war affected everyone. Each person knew a close friend or family member who died or came back maimed for life.

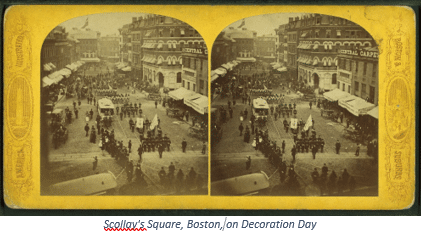

It was in the South during the war when the first commemorative activities arose. In the North, the movement was spearheaded by Union Gen. John A. Logan, who chose May 30, 1868 as the first Decoration Day. As the commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a veterans' organization of Union soldiers, he led efforts not just to recognize fallen heroes, but also to push the nation to expand the pensions that the survivors needed so much. Without publicity and pressure, people and their sacrifices will be forgotten by the rising generation. This is what was happening by the 1880s. By the early years of the 20th century, the surviving servicemen of the Civil War were growing old, and it was natural for them to want the young to not forget their “full measure of devotion,” as President Abraham Lincoln stated in his Gettysburg Address. The services, prayers, and parades all across America on Decoration Day were a great way to perpetuate the memories.

The collective memory of society is important. In the Price Genealogy blogs, we have talked about personal memories, journal keeping, interviewing older relatives, and writing memoirs. We are grateful for those who help us remember with soberness events like the Holocaust. It is said that history is written by the victors. Nowadays, however, we live in an age where we try not to squelch any voices. As genealogists, we want our own family stories to not be forgotten. We worry that our children will throw out our research and will not care about our stories. The Civil War generation was no different.

The following thought by a Civil War veteran in 1913 concerning young people illustrates the challenge. He said that they have a “tendency . . . to forget the purpose of Memorial Day and make it a day for games, races and revelry, instead of a day of memory and tears.”[1] Some writers point out that our failure to remember will doom us or our descendants to relive the horrors and injustices of the past, if we have to learn anew by sad experience.

Memorial Day is the time to remember the millions who died in other wars, including World War I and World War II. Closer to our own times, many can still feel the sacrifices of those who fought and died in Korea, Vietnam, in wars in the Middle East, and so many other conflicts. A history of this day follows.

Commemorations in the South

Women in the Confederate States of America placed flowers on the graves of their fathers, brothers and sons who fell in battle. Columbus, Georgia was one of the first places to host a formal memorial event. The Ladies’ Memorial Association of Columbus sent letters throughout the South encouraging others to establish their own events in April and May of 1866.

Following the Civil War, southern and northern states followed their own plans for commemorations. It was 1874 when Confederate Memorial Day became an official holiday in the South. As time went on, these events were not just about remembering individual soldiers who died, but the organizers expanded the scope of memory to include the whole Southern cause. They put up monuments and wrote their version of the history. The United Daughters of the Confederacy grew to 100,000 members by the beginning of World War I. Traditional white southern culture was promoted. By the time of the First World War, the theme of memorial speeches had become more nationalistic.

Memories are never quite static and true to the original events. People shape memories to edify different audiences or a new generation. They wanted their culture perpetuated, but we know today the importance of listening to the voices of others whose ancestors came from different channels of American life. The former slaves had their own stories to tell, and the interviews by the Federal Writers’ Project of former slaves in the 1930s have left us a treasure of insights.

The northern and southern states generally held separate memorial events. But by the 1880s and 1890s, there were more and more activities planned where Blue (Union) and Gray (Confederate) came together. At the 50-year commemorations of the battles of Gettysburg and Chickamauga, there was a large Blue-Gray Reunion in Washington, D.C. President Woodrow Wilson spoke at Gettysburg. It was a sign that the nation was slowly healing to have elected the first president from a southern state (Virginia) since the Civil War.

Commemorations in the North

There were a lot of commemorations near the end of the Civil War, especially as people learned of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Ten thousand freedmen, many having served with the U.S. Colored Troops, joined in a procession of people who had participated with the reburial of 250 Union soldiers. The dead had initially been buried in a mass grave at the Charleston, South Carolina race track that had been used as a prisoner of war camp. The marchers put flowers on graves and sang songs.

While the war raged on, the United State government established the first national cemeteries. There were seventy-three of these national cemeteries by 1870. Gen. John A. Logan, leader of the veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) mobilized his organization. He set May 30th as the date to honor those who had died, and this date continued from 1868 to 1970. Flowers were in full bloom by then.

With each passing year, the ceremonies became more organized as the GAR tried to standardize some of the practices by distributing a handbook. Since one of the goals of the celebrations was to lobby for pensions, the 1884 handbook admonished families to help their soldier husbands or fathers to keep from drinking too much at the events. Good appearances certainly could help the cause.

Historians have studied the changing nature of the speeches that were given. At first, talks often rehearsed the evils of the vanquished enemy. Later, they mixed themes of sacrifice and rebirth with religion and nationalism. The tens of thousands of immigrant Catholic Germans and Irish who fought for the Union had come through the crucible of war side by side with other Americans, and could now feel greater acceptance in American society. The commemorations helped heal some old wounds.

By 1890, all of the northern states had made Decoration Day an official state holiday. The ceremonies on May 30th each year were planned by the Women’s Relief Corps, the female auxiliary of the GAR, which had grown to 100,000 members. Whole communities came out to march from their town to their cemetery, where they placed flowers on graves, cleaned it up, sang songs, read poems, and recited verses from the Bible. The services in the cemeteries were often somber and reflective.

The term “Memorial Day” was first used in 1882, but would not predominate until after World War II. As new generations were born who had no recollection of the bloodshed of the Civil War, activities on Decoration Day became more recreational. The new Indianapolis Motor Speedway race was scheduled for Memorial Day in 1911, but it brought the ire of the now elderly veterans of the GAR. As seen in the quotation above, some felt the day had become too much about games and general festivities. The GAR thought they had succeeded in diverting the popular Indy 500 with some legislation passed in 1923 by the Indiana 1923 legislature, but the governor vetoed the bill. The newly created American Legion, for the veterans of World War I, took the side of those wanting the big race on Decoration Day.

After World War I, Decoration Day commemorated those who made the ultimate sacrifice from all of America’s wars. A new tradition came out of the First World War, as the red poppy became a symbol of remembrance. In 1915, Lt. Col. John McCrae penned the famous lines to his poem, In Flanders Field, which mentioned the poppies that grew around soldiers’ graves. Three years later, an American professor and YWCA volunteer composed her poem, We Shall Keep the Faith, which again referred to the poppies growing around soldiers’ graves. She became The Poppy Lady and by 1920 or 1921 the flower was proclaimed by some groups as the symbol of remembrance. She promoted the sale of silk poppies to raise funds to assist wounded veterans.

Confederate Memorial Day remains an official state holiday in several southern states. In 1967, federal law legally changed the name of the national commemoration from Decoration Day to Memorial Day. Another law went into effect in 1971, which officially made Memorial Day the last Monday in May, thereby giving people a three-day weekend. Groups like the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War have lobbied for Memorial Day to be moved back to May 30th in order to help people see it more meaningfully. Unfortunately, some people see the day as simply a day off from work or a recreation day marking the unofficial first day of summer.

Discovering our place in American history

What can we do to “keep faith” with those who died for us, as Moina Michael wrote? Do you know who your ancestors were and where they are buried? Were they soldiers? Did any of them die in the service of their country?

Our ancestors have come from very diverse backgrounds and historical traditions. Some families have a tradition of visiting cemeteries and others do not. Some have family members who died serving in the military, and others do not.

People need to learn their own family history and find meaning in the sacrifices that so many have made for this great nation. As you discover your ancestors’ journeys through history, it will help you feel a part of the great events of the past.

Our researchers at Price Genealogy can help you find your military ancestors. We can help you join hereditary societies such as the Daughters of the American Revolutions and many others. If you would like to start investigating on your own, Fold3 (www.fold3.com) and Ancestry (www.ancestry.com) are great places to begin. This weekend, until May 26th, the genealogy website MyHeritage (www.myheritage.com) is offering all of their military records for free. Best wishes to you as you contemplate the meaning of Memorial Day and seek to see yourself and your family in the annals of American history.

Greg

[1] “Memorial Day” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memorial_Day); citing Nicholas W. Sacco, “The Grand Army of the Republic, the Indianapolis 500, and the Struggle for Memorial Day in Indiana, 1868-1923,” Indiana Magazine of History 111.4 (2015): 349-380, p. 362.

Do you have any other questions about Memorial Day genealogy that we didn't answer in this post? Let us know in a comment below!