Land Records Part 1

11

11Jul

"Why, land is the only thing in the world worth workin’ for, worth fightin’ for, worth dyin’ for, because it’s the only thing that lasts.”

—Gerald O’Hara, Gone with the Wind

The above quote sums up the life and breath of America. The possibility of owning land attracted many Europeans who had no hope of owning land in their home countries. Land was awarded to military veterans. The Homestead Act granted free land to those migrating westward who would improve their new land. This drew immigrants as well as people from the eastern states.

Land ownership guaranteed wealth, so land transactions needed to be recorded. It was so important to have records of land transactions that they were rerecorded in the event any were destroyed, such as with burned courthouses.

Gerald O’Hara’s words resonate not only with our ancestors who migrated in pursuit of land but also with genealogists. Land records are a treasure trove of information about our ancestors, yet they are often overlooked in genealogical research. This blog series will delve into the uses of land records and guide you on how to unearth these invaluable resources.

History of land in the USA

When colonization efforts began in America, the crown granted proprietors land, which the proprietors then granted to colonists. This land was either sold or given as a reward to those bringing indentured servants. Indentured servants who finished their indentures also received land.

After the Revolutionary War, the new U.S. government did not have money to pay the veterans but it had land west of the Appalachians. As that land was being surveyed, certain sections would be reserved for the military and given to veterans as bounty land. Some veterans and their heirs moved to their bounty land, and others sold their bounty land warrants. Bounty land was awarded to both Revolutionary War and War of 1812 veterans.

An ordinance of 1785 provided a systematic process for surveying, planning, and selling townships west of the Appalachians. Land sales would generate revenue for the U.S. government. The new survey system, discussed shortly, was started in Ohio.

The Homestead Act was enacted in 1862 to draw people to the West. It provided free land to those who would inhabit it for five years and improve it by growing crops or raising stock. This gave women and formerly enslaved persons an opportunity to own land. Any head of household at least 21 years old was qualified, regardless of race or gender.

Railroad land grants were another way to promote settlement in the West. As the railroad companies built the railways, they purchased land from the federal government. They would then sell the land not needed for railways and train stations.

Surveying

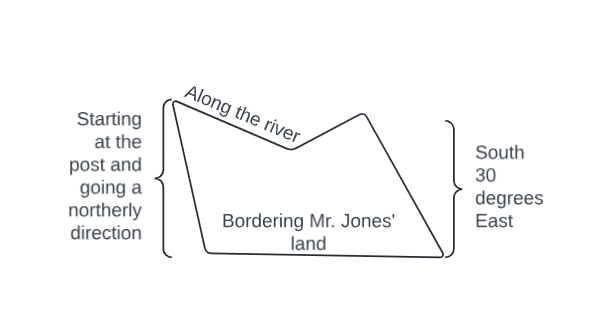

Two different surveying systems are used in the United States. The original thirteen colonies and several other states are state-land states using the metes and bounds surveying system. The metes and bounds surveying system starts with a landmark, indicates a direction and a distance, and then indicates another landmark with a new direction and distance. This continues until the original landmark is reached again, usually resulting in odd-shaped tracts of land. The diagram below exemplifies what you might see in a land description and plat.

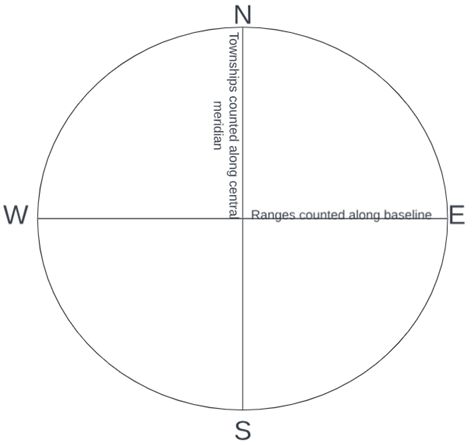

Federal-land states are those where the federal government (rather than the state or colony government) granted the land. These thirty states use the township-range survey system, which counts from a central meridian and baseline. Each township is numbered north and south at six-mile increments, and each range is numbered east and west at six-mile increments, as shown in the chart below.

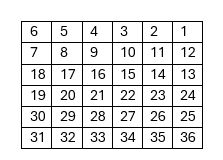

Each township-range square is divided into 36 square-mile sections, which are numbered, as shown in the chart below.

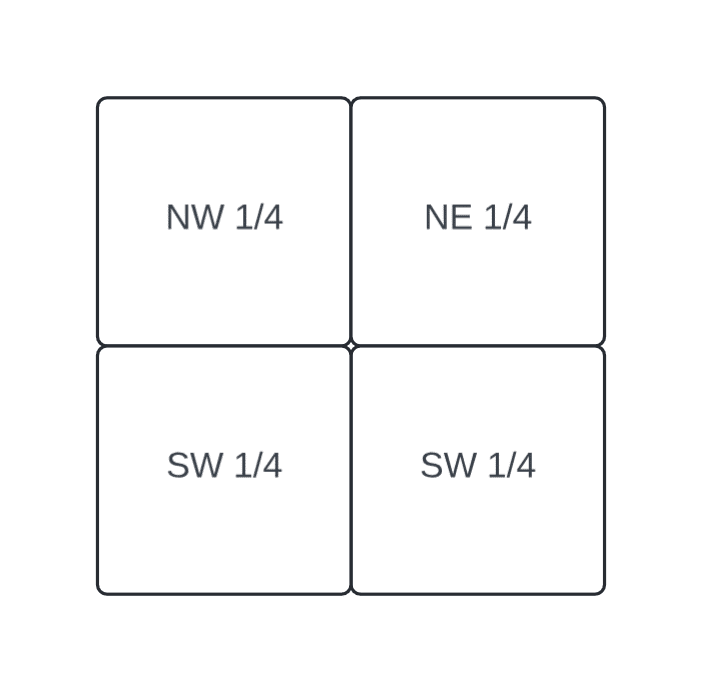

Each of these sections is further divided. One square mile is 640 acres. A homestead plot was 160 acres or one-quarter of a section. This survey system resulted in square and rectangular tracts of land with systematic legal descriptions, such as Township 3N Range 4W section 18 NW ¼. The chart below shows the quarter sections.

Obtaining land

Ancestors who owned land had to complete paperwork, which is valuable to genealogists today. The original settlers in an area would receive the land from the proprietors or the government.

A settler in a state-land state (or colony) would make a claim on a piece of land and pay to have it surveyed. The surveyor would use a chain to measure distance and a compass to measure angles and provide a written description of the land. This description often indicated landmarks such as trees, stones, rivers, and roads and indicated who owned the bordering land tracts.

In a federal land state, the settler would apply for a land grant at the local land office. A land entry case file was then created. Homesteaders would then settle on the land and begin improving it. Other settlers would purchase the land, usually for a cheap price. The final step, whether for homesteaders or purchasers, was to issue a patent, indicating land ownership.

In some cases, the person who began the process was different from the person who finished the process. Some veterans (or widows) who obtained bounty land would sell their warrants rather than move. Many homesteaders abandoned their claims, and another would take over the claim.

Sometimes, squatters (AKA vagabonds or land pirates) would settle the land before making any legal claims. Squatters usually began building on the land and growing crops. Living this way had risks, such as the possibility of the land being sold out from under them. This was especially risky for those too poor to buy the land themselves.

Some states passed preemption acts, which gave squatters first dibs on purchasing the land if they could prove their settlement on or improvement of the land. These preemption rights even applied in military districts. On the other hand, if landowners petitioned for it, the government could forcibly remove squatters.

Types of land records

The paper trail left by land ownership, acquisition, and disposal is valuable to genealogists today. The process described above created entries, warrants, surveys, plats, and patents. When the land was sold from owner to owner, a deed was created. The landowner kept the original deed, and a copy was transcribed into a deed book at the recorder’s office. In the event of a burned courthouse, landowners were encouraged to reregister their deeds, so this record type was largely protected from record destruction.

Land ownership affected other records besides land records. Land sales were sometimes announced in local newspapers. Many places kept marriage records earlier than other vital records because of dower rights laws (the widow’s right to a third of her late husband’s property). Probate records indicate when land was passed down to heirs, as a new deed may not have been created in these cases. Land disputes were settled in court, so they can be found in court records.

Understanding the laws of your ancestors' time and place is important. Deeds were not required in the early days. When deeds were required, each time and place had different regulations on what made a deed legal. If a land-owning ancestor left no will, the intestate law would have determined how the land was divided among heirs. What rights did women have? What were the laws regarding guardianship? These would affect who had control over the land. Were there entails on the land? These limits limited future property transfers, and some states did away with them. Not every ancestor understood the laws of their own time, so it’s possible for an ancestor to have tried selling land that they rightfully couldn’t sell.

This article reviewed the background information of land records. The next article will focus on their genealogical value, including how to find them and use them in research.

By Katie

Resources

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/metes-bounds-land-plats-solve-genealogical-problems/?search=land

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/comparing-plats-of-land-with-deeds-and-grants/

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/land-records-solve-research-problems/

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/u-s-land-records-state-land-states/

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/lineage-of-land-tracing-property-without-recorded-deeds/?search=land

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/neighborhood-reconstruction-effective-use-of-land-records/?category=records&subcategory=land&sortby=newest

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/squatters-pre-emptioners-and-thieves-early-land-records/?category=records&subcategory=land&sortby=newest

- Photo taken by Diane Rogers 2019

- All images were created by author