LABOR DAY – A Thank You to American Workers!

3

3Sep

Those who get to take a day off work this Labor Day can thank the labor activists of the 19th century who succeeded in making it a federal holiday on 28 June 1894 in gratitude of the American Worker.[1] But change did not happen overnight. It was recognized by individual states before it was a federal holiday, as municipal ordinances were passed beginning in 1885 and 1886. There are varying accounts of who first suggested the holiday, but the idea was proposed around 1882. And later that year, the first Labor Day holiday was celebrated on 5 September 1882, supported by the Central Labor Union. They celebrated again the next year on the same day. This idea of a “workingmen’s holiday,” soon caught on in other industrial centers around the country.[2] New York City was the first to introduce a bill, but Oregon was the first state to pass a law recognizing Labor Day in 1887.

Getting the day off work is just one of the many benefits and protections afforded to the contemporary American worker. Workers now generally get a defined part-time or full-time schedule. Employers are required to pay time and a half for those who work over 40 hours in a week. Full-time jobs usually come with benefits, including healthcare and retirement. The minimum age a child can work is flexible in each state, but is generally 14 or older. But this was not always the case.

During the height of the Industrial Revolution, it was common for factory workers, miners, and mill workers to work 14-16 hour shifts six days a week. These hours were worked for very little pay. While a middle-class man could earn enough money to support his family, a working-class man made less than the minimum needed to survive. This necessitated having other means of income including the wife selling handmade goods, the family taking in boarders, and sending children to work. Deplorable working conditions often meant insufficient access to fresh air, sanitary facilities, or breaks. The children who worked long hours were often unable to attend school, so this perpetuated the poverty cycle.[3]

During the height of the Industrial Revolution, it was common for factory workers, miners, and mill workers to work 14-16 hour shifts six days a week. These hours were worked for very little pay. While a middle-class man could earn enough money to support his family, a working-class man made less than the minimum needed to survive. This necessitated having other means of income including the wife selling handmade goods, the family taking in boarders, and sending children to work. Deplorable working conditions often meant insufficient access to fresh air, sanitary facilities, or breaks. The children who worked long hours were often unable to attend school, so this perpetuated the poverty cycle.[3]

It was in the best interest of factory owners to employee children. Children were less likely to strike than adults and would accept lower wages.[4] There were no laws protecting them and working-class families needed the extra income. Before free public education, poor families could not afford to send their children to school. Additionally, children were more agile than adults for working the machinery.[5] One source says that children were working as young as 5 and another as young as 3.

It was in the best interest of factory owners to employee children. Children were less likely to strike than adults and would accept lower wages.[4] There were no laws protecting them and working-class families needed the extra income. Before free public education, poor families could not afford to send their children to school. Additionally, children were more agile than adults for working the machinery.[5] One source says that children were working as young as 5 and another as young as 3.

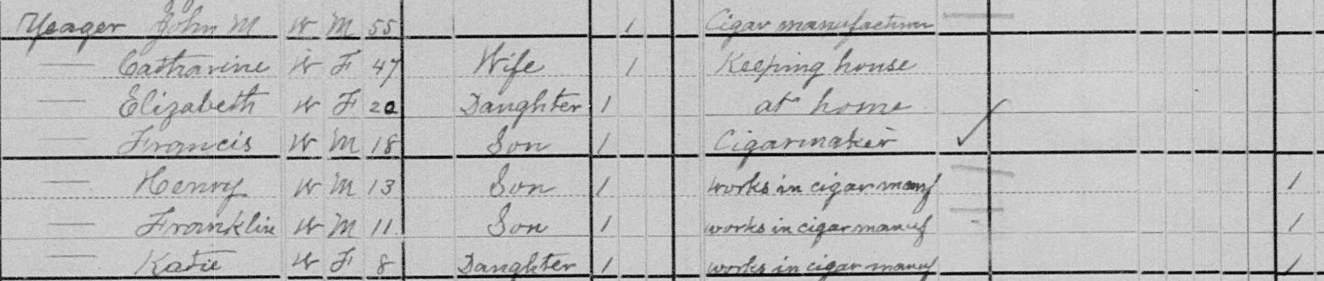

The German-American Yeager family in 1880 Manheim, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, had to send all four children to work in a cigar factory, including the youngest daughter, Katie, age eight.[6] The youngest three were also receiving some education since they “attended school” at some point in the year.

Working conditions were dangerous as there were no safety features. It was common for children to be injured on the job.[7] Some were even killed. Sadly, the factory owners saw their workers as easily replaceable. They only cared about cleaning up the mess.[8] In 1860 in Hebron, Tolland, Connecticut, the Silk-mill Boarding House (probably the Turner Silk Mill) employed children as young as 10.[9] In the same year, in Cumberland, Cumberland, North Carolina, eight-year-old Barney Powell worked in the cotton mill along with his siblings (age 10, 15, 17, and 19).[10]

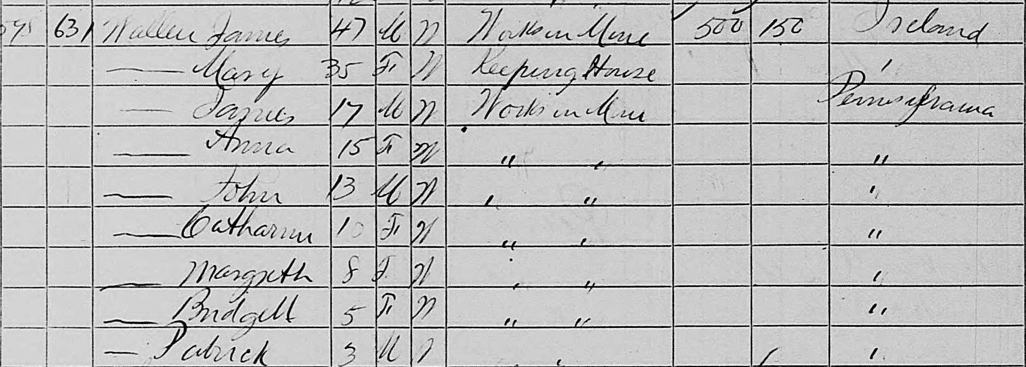

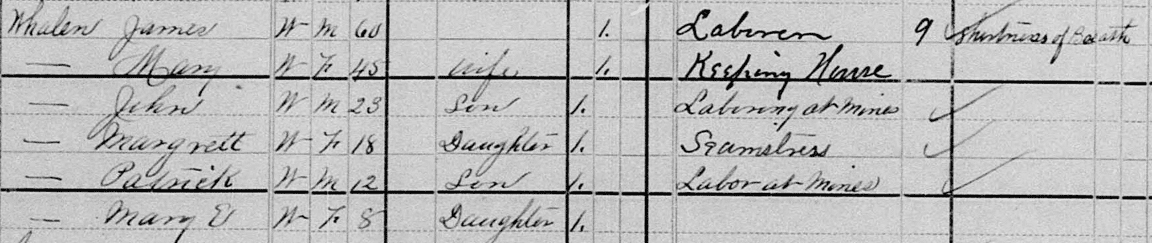

Before the federal child labor laws were passed in the 1930s, many states passed child labor laws but were then unable to enforce them.[11] In the 19th century, Pennsylvania had been reported as one of the worst offenders of exploiting child labor. Surely this must have seemed the case to Irish-born James Wallen and his family who lived in Butler, Schuylkill, Pennsylvania, in 1870. He and his wife Mary had seven children and all seven were working in the mines, even down to their youngest child, Patrick, age three![12]

In 1880, poor James was largely unemployed, having not worked 9 of the last 12 months because he was sick with “shortness of breath,” no doubt due to the working conditions in the mine.[13] Three of his four children were still working, including his 12-year-old son, Patrick, who worked as “labor at mines.”

The Pennsylvania Child Labor Committee was formed in 1904 to promote labor reform. This organization worked for years lobbying for reform and investigating child labor. Their investigations led to the dismissal in 1912 of the Pennsylvania factory inspector who had been dismissive of child labor law violations. The following year, the Pennsylvania Governor created the Department of Labor and Industry. A new child labor act was passed in 1915, which restricted how many hours a child could work, placed age restrictions on employment in various industries, and mandated educational requirements for working children.[14]

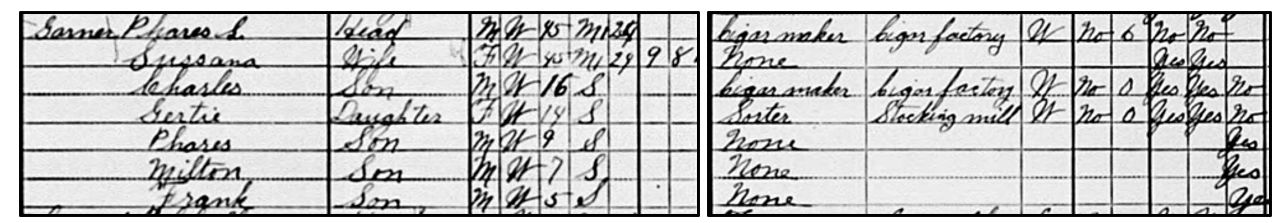

Even though the new child labor act was not passed until 1915, most families by this time did send their youngest children to school if they could. This can be seen in the Garner family, who lived in Warwick Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in the early 20th century. In 1910, Phares Garner was a cigar maker in a cigar factory. His wife, Susan, did not work but his teenage children did. Sixteen-year-old Charles was a cigar maker and fourteen-year-old Gertie was a sorter at a stocking mill. His three younger children, however, were in school and not working.[15]

In 1920, everyone in the household was working except the mother. Children Charles, Phares, and Frank, ranging in age from sixteen to twenty-six, worked as cigar makers at the cigar factory with their father. Son Milton Garner, age seventeen, worked as a laborer in a chocolate factory. [16] He most likely worked at Wilbur’s chocolate factory, which was in Lititz, Pennsylvania, which borders Warwick Township. Henry Oscar Wilbur and Samuel Croft formed a business partnership in 1865, making and selling candies in Philadelphia. [17] As their business continued to grow, they decided to build a separate factory for chocolates. In 1884, they divided the business into separate operations, forming the company H.O. Wilbur and Sons to manufacture chocolate. The business was passed onto Wilbur’s sons and grandsons and continued to grow and expand. In 1913, a building was added in Lititz. It is most likely here that Milton Garner worked.

Whether working in a silk factory, cigar factory, in the mines, or a chocolate factory, our working-class ancestors had long hours of toil to bring in barely enough money to survive. We can thank many who championed for reform and better regulations so that our modern-day working conditions are much improved from those of our ancestors.

If you would like to learn more about your working-class ancestors, reach out to Price Genealogy. We would love to help!

By Emily & Katie

All Images are in the Public Domain

[1] US Department of Labor, “History of Labor Day” (https://www.dol.gov/general/laborday/history: accessed 2 September 2024).

[2] History.com, Labor Day 2024, updated 6 August, 2024, original 13 Apr 2010 (https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/labor-day-1: accessed 2 September 2024).

[3] Historylia, “A Day In The Life Of A Working In The Industrial Revolution,” video, uploaded 19 October 2022; YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0I4TNYTw4k4 : accessed 29 August 2024).

[4] Vox, “These photos ended child labor in the US,” video, uploaded 28 June 2019; YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ddiOJLuu2mo : accessed 29 August 2024).

[5] History Crunch, “Child Labor in the Industrial Revolution - Video Infographic,” video, uploaded 24 April 2022; YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nN-mmQuyU_8 : accessed 29 August 2024).

[6] 1880 U.S. Census, population schedule, Manheim, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, John M. Yeager household; index with images, image 32 of 34, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/50258929:6742?tid=&pid=&queryid=86b82fa9-69ab-4969-8694-29dc2f6e1b57&_phsrc=Ccc389&_phstart=successSource: accessed 2 September 2024).

[7] Vox, “These photos ended child labor in the US,” video, uploaded 28 June 2019; YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ddiOJLuu2mo : accessed 29 August 2024).

[8] Nutty Productions, “The Cruel Life of Children During the Industrial Revolution,” video, uploaded 30 October 2021; YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cloO-2d1xJg : accessed 29 August 2024).

[9] 1860 U.S. Census, population schedule, Hebron, Tolland, Connecticut, Silk-mill Boarding House; index with images, image 21 of 39, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/16715073:7667?tid=&pid=&queryid=17dc607e-56d4-45a8-9778-e9cf5febca1d&_phsrc=Ccc395&_phstart=successSource: accessed 2 September 2024).

[10] 1860 U.S. Census, population schedule, Cumberland, Cumberland, North Carolina, Benjamin Powell household; index with images, image 101 of 111, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/41172703:7667?tid=&pid=&queryid=6f7de579-7d52-44f4-afec-3f0e454fa31d&_phsrc=Ccc405&_phstart=successSource: accessed 2 September 2024).

[11] Reid Maki, Timeline of Child Labor Developments in the United States, Stop Child Labor, 2010, viewed 30 August 2024, <https://stopchildlabor.org/timeline-of-child-labor-developments-in-the-united-states/>.

[12] 1870 U.S. Census, population schedule, Butler, Schuylkill, Pennsylvania, James Wallen household; index with images, image 84 of 150, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/11273231:7163?tid=&pid=&queryid=a9bebc31-1425-49b3-a78b-0d6f61cea064&_phsrc=Ccc382&_phstart=successSource: accessed 2 September 2024).

[13] 1880 U.S. Census, population schedule, Girardville, Schuylkill, Pennsylvania, James Whalen household; index with images, image 10 of 55, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/595335:6742: accessed 2 September 2024).

[14] Jessica Markey Locklear, The Rise of the PCLA: Child Labor Reform in Pennsylvania, In Her Own Right, after 2015, viewed 30 August 2024, <http://inherownright.org/spotlight/featured-exhibits/feature/the-rise-of-the-pcla-child-labor-reform-in-pennsylvania>.

[15] 1910 U.S. Census, population schedule, Warwick Township, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, E.D. 147, sheet 8B, household of Phares L Garner; FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/: accessed 29 August 2024).

[16] 1920 U.S. Census, population schedule, Warwick Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, E.D. 135, sheet 6B, household of Phares Garner; FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/: accessed 27 August 2024), image 260.

[17] The History of Wilbur Chocolate, Wilbur Chocolate, 2015-2024, viewed 30 August 2024, <https://www.wilburbuds.com/wilbur-history>.