Irish Research, Part 2: Is it really too hard?

30

30Sep

Have you heard it said that Irish research is too hard, or that “all the records have been destroyed”? Well, we have to admit there is some truth to these statements. But not all of the records of genealogical value have been destroyed and there are some ways to try to get around the loss of records. Irish research has been made a lot easier in recent years by efforts to index existing records and to put those indexes and some images in searchable online databases. But first, let’s talk about the destruction of records.

Record destruction

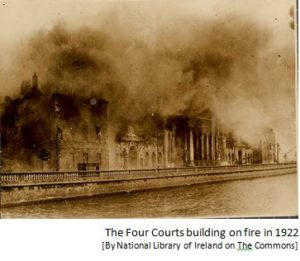

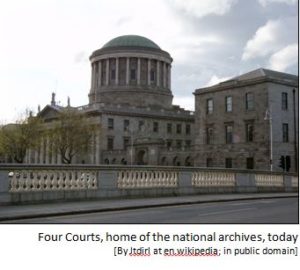

You no doubt have heard about the Irish Civil War of 1922-23 which resulted in the country being split into two parts—the independent Republic of Ireland encompassing about three-fourths of the island, and Northern Ireland, which is still part of the United Kingdom. During that civil war the Four Courts building in Dublin, which housed the public records office, was burned. Large collections of records of genealogical value were destroyed. These include:

- Pre-1861 census records

- Church of Ireland (Anglican Church) records

- Wills and other probate records

- Court records

(NOTE: Not all of these classes of records were destroyed. In some cases fragments or copies survive. We will discuss these in more detail later.)

Not all record destruction was the result of the war. Some was due to poor choices on the part of officials. The 1861-1891 censuses were purposely destroyed when the statistics had been compiled and it was believed they were no longer needed. So the only censuses available in full are 1901 and 1911.

You may be familiar with Bishop’s Transcripts kept by the Anglican Church. These were copies of the registers the ministers were required to make each year and send in to the Bishop of their Diocese. Unfortunately, these records no longer exist for the Church of Ireland. Probably, at some point in time, they were thought to be unnecessary duplicate records and were destroyed. If that is true, then that was another bad choice! Approximately two-thirds of Church of Ireland parishes have no surviving records.

A large proportion of all wills and probate records were destroyed, including those of the pre-1858 church and post-1857 civil district courts, as well as the records of the highest-level courts.

As one might assume from the name of the public records building in Dublin—Four Courts—the building was the home of Ireland’s four courts of Equity: the Exchequer, Chancery, Common Pleas, and the King’s/Queen’s Bench. Most of the records of these four courts were destroyed in the fire.

So what survives?

Let’s look at what records survive, what has been indexed and digitized, and how best to access them.

Civil Registration Records

Civil registration of births, deaths, and all marriages began in 1864. In addition, registration of Protestant marriages began in 1845. These records were not housed at Four Courts and were not destroyed. Perhaps the only draw-back is that not everyone complied with registration when it first began, but by the late 1870s most people did. The records are just like those of England and Wales, where the births give mothers’ maiden names, the marriages give the same information as the Church of Ireland records (including the names and occupations of the fathers of the bride and groom), and the deaths are inadequate—meaning they don’t give one’s birth date or place or the names of parents (except sometimes for children).

The records are well indexed and the indexes and record images are available through several websites including FamilySearch.org and IrishGenealogy.ie. Keep in mind that the indexes give the name of the district where an event took place rather than the actual place of the event. A good index to place names is found online at https://thecore.com/seanruad/. If you have a place name derived from your U.S. or Canadian sources, this database will identify the parish and the Poor Law Union, which later became the registration district. You can try spelling variations or just part of a place name.

Census Records and Substitutes

The 1901 and 1911 censuses, as well as the surviving fragments of the 1821-1851 censuses (along with a description of what survives), are indexed on the website of the National Archives of Ireland at: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie.

The Irish government began to provide pensions to its older citizens in 1908, but in order to qualify for the pension, individuals had to provide proof of their birth or age. But civil registration of births did not begin until 1864, and the earliest applicants were born before that time. Church records were the next best source, but they were often difficult to access. But one source that was deposited and readily accessible was census records, in particular, the informative 1841 and 1851 censuses. So searches were made for census records showing applicants as a child in their parents’ household, and extracts of the records were made and filed with the applications. These extracts serve as census substitutes. They are called ‘Census Search Forms’ and they are indexed on FamilySearch.org as well as the website of the National Archives of Ireland at http://censussearchforms.nationalarchives.ie/search/cs/home.jsp.

Tax records can be a good census substitute, especially for the years before censuses were taken, but for Ireland there are two great land-based taxes compiled during census years which are the best census substitutes: The Tithe Applotment Books compiled 1823-1837 and Griffith’s Primary Valuation compiled 1847-1864.

The Tithe Applotment Books were compiled for the purpose of determining how much tithe money agricultural land-holders or occupiers should pay to the Church of Ireland. Naturally, non-members of the Church were not happy about having to pay the tithe and sometimes resisted. In addition, the poorer sub-tenant classes did not pay the tax, and urban areas were not included. So the books do not include everyone in Ireland but they are still a very important source for their time period. In addition to names, they identify residences.

The Primary Valuation was Ireland’s first comprehensive property tax. It lists most people in Ireland and gives addresses, describes the property taxed, and gives the amount of tax. However, both the Applotment books and the Primary Valuation list the heads of households only. So while they can help you identify where your ancestral family lived, they will not supply the names of every family member as the census did. Still, they are far better than nothing, and they are well indexed online. For the Tithe Applotment Books, use FamilySearch.org or http://titheapplotmentbooks.nationalarchives.ie/search/tab/home.jsp. For Griffith’s Primary Valuation, use http://www.askaboutireland.ie/griffith-valuation/. The printed valuation books are also viewable on this free website.

There are a number of other records (many of them tax records) which serve as census substitutes, particularly for the pre-1821 years. You will find an explanation of these on FamilySearch.org in the Research Wiki. Search for the topics of ‘Ireland Census’ and ‘Ireland Census Substitutes.’

Church Records

Not all Church of Ireland records were destroyed. While most registers and other records had been sent to Dublin “for safe keeping,” not all were. In addition, some ministers made copies of their registers before they sent them in, so some Church of Ireland registers survive.

Roman Catholic records were not deposited at Four Courts and were not destroyed. The same is true of records of the Presbyterian Church and other religious denominations.

In Part 3 of this article, we will review church records in detail.

Barbara