Irish Research, Part 1: Identifying your Irish immigrant ancestor and their place of origin

30

30Aug

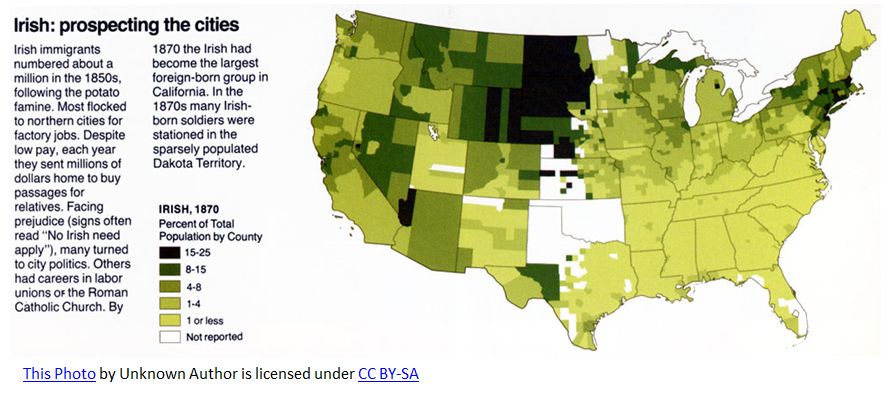

If you claim Irish ancestry, you certainly are not alone. According to the 2017 American Community Survey[1], conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, about 33 million Americans (10.1 % of the total population) self-identified as having Irish ancestry and another 3 million self-identified as having Scots-Irish (Northern Ireland) ancestry. Ireland is second only to Germany as the European place of ancestral origin claimed by respondents to the survey. So, a large portion of the U.S. population could have a desire to know more about their Irish origins and they may wonder, where do I start? The answer is the same for family history researchers the world-over: start with what you know.

What do you know and what do you want to learn?

When beginning any family history project, you start by determining what you know about your family and what you want to learn. When your project includes an emphasis on tracing the family back to their country of origin, you need to answer these important questions:

- Who was my immigrant ancestor?

- When did he or she immigrate?

- Did he or she immigrate in the company of others?

- Did he or she settle in an area where other people of their ethnic origin settled?

- Did he or she become a naturalized citizen?

- Did the family leave any clue as to where they came from?

When it comes to researching your immigrant Irish ancestors, knowing the answers to these questions will help increase your chances of success.

Obviously, you have to identify your immigrant ancestor before you can have any hope of success in tracing him or her back to their place of origin. Knowing just the family surname is of little help.

Knowing when your ancestor immigrated will make a huge difference. If he or she immigrated in the mid-1800s they will be much easier to trace than if they came in the mid-1700s.

Immigrants often came in family groups, or along with neighbors, especially early immigrants. Knowing whether your ancestor immigrated along with others, and taking the time to do a little research on those others, may help you solve your research problems.

If your immigrant ancestor settled in an area where other people of their ethnic origin had previously settled, they may have some relationship or connection to those earlier settlers. Perhaps they settled where other family members, former neighbors, or associates were established. Learning more about those other family members, neighbors, etc, may help you solve your research problem.

If you can find a clue, any clue, as to where your immigrant ancestor came from in their country of origin, you will be way ahead of the research game.

U.S. Sources

There are a number of U.S. sources that can help you identify your Irish immigrant ancestor and his or her place of origin. Here are a few suggestions.

- Printed county histories. In the years following the Civil War, many U.S. counties published histories which included biographical sketches of their residents. These sketches may include the names and historical information on the parents and even grandparents of the people profiled, and may mention where they came from. If their place of origin is given as another, more eastern, U.S. locality, look for histories of that area too. Eventually you may find mention of a locality in Ireland.

- Census records. Pre-1850 U.S. census records give the name of the head of household only and do not give birthplace, but the 1820 and 1830 censuses include something that can be overlooked—a column to indicate whether the person was a foreigner or alien not naturalized. If marked, then the person was likely a recent immigrant. The 1870 census asked whether males were citizens and also whether one’s mother or father was of foreign birth. The 1900-1930 censuses asked for year of immigration and whether naturalized. Post-1840 Censuses usually give only the country of birth but sometimes they will give more.

- Naturalization records. The U.S. started keeping naturalization records in 1790, but the records rarely give place of origin, other than the name of the country, until the late 1800s or even early 1900s. Nonetheless, you should look for naturalization records for your immigrant ancestor. Naturalization could be granted by county, state, and federal courts, so you may need to check on each level. Start your search with databases on Ancestry.com or FamilySearch.org. Canada has never required naturalization.

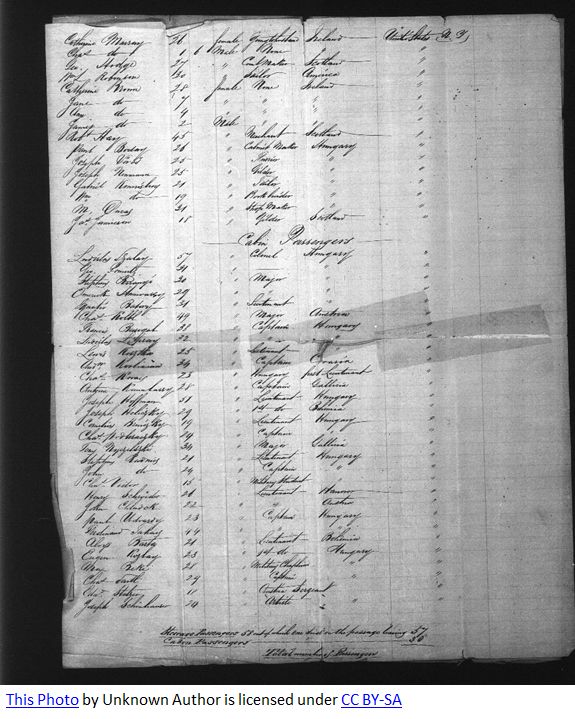

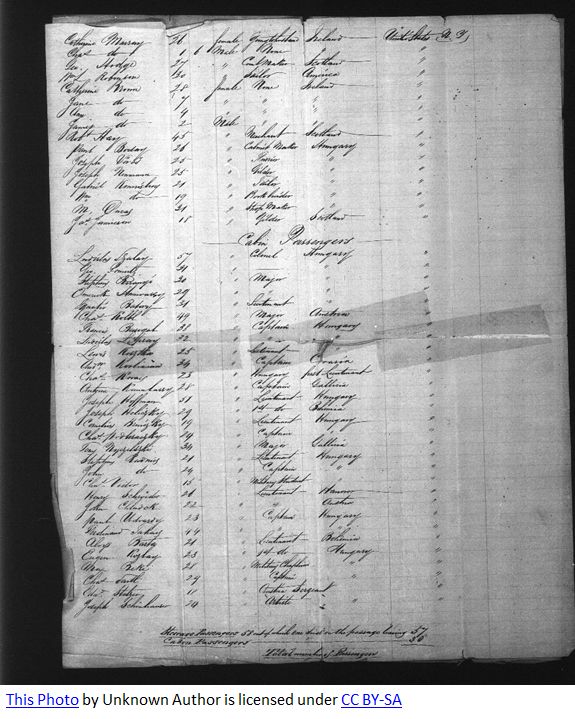

- Passenger lists. Official U.S. passenger lists date from the 1800s. Those for Canada date from 1865. You might think they would be an important source for finding a place of origin, but not necessarily. They may give only Ireland and the port of departure, such as Cork or Londonderry, but not the actual residence in Ireland. Nonetheless, there are important reasons to search them. For one, they are well indexed. For another, they will show whether your immigrant ancestor came alone or with someone else. Both websites Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org have indexes to U.S. passenger lists. There is more than one way to approach a search on both websites, but here is one suggestion for each.

- On Ancestry.com, click on ‘Search’ and select ‘Immigration & Travel.’ You can narrow the search to just ‘Passenger Lists,’ then search for your ancestor by name. To filter the list of results, add a range of years for the arrival date. Select a particular database title to see just those results.

- On FamilySearch.org, go to ‘Search,’ then ‘Records’ and type in your ancestor’s name. Restrict the search by selecting the filter ‘Type’ and ‘Immigration and naturalization,’ then do the search. In the left-hand column, scroll down and click on ‘Other Year’ then select the century, either 1800 or 1900. Narrow the search to the likely decade of immigration.

- Pre-1800 immigrant lists. There are numerous sources which may list early immigrants, such as the signers of a colonial town charter. A man named of P. William Filby, and his army of volunteers, trolled for years through such sources, printed and otherwise, and compiled a list of people named. The list was published in a series of printed volumes which have been transcribed and turned into a searchable database on Ancestry.com titled “U.S. and Canada, Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s.” The indexed sources may not give a place of origin for your named ancestor, but they may give places of origin for the leaders of your ancestor’s community, and researching those people may lead you to the place of origin of your ancestor.

- Newspapers. Newspapers, and particularly obituaries, may identify your immigrant ancestor’s place of origin in Ireland. The more recent the death date, the greater chance the obituary will include this kind of detail. If your ancestor died early but their contemporary relative lived to an old age, check for an obituary for the relative. Newspapers are becoming well indexed on multiple websites (most accessed by subscription) including:

- Genealogybank.com

- Newspapers.com

- Newspaperarchive.com

- Gravestones. Gravestone inscriptions sometimes give the place of birth of a person born in Ireland who died in the U.S. or Canada. Look for your ancestor’s gravestone and see if such information is given. Start with the website www.findagrave.com. In addition to the actual gravestone inscription, the memorials often include more details that family members have researched and added. Again, look not just for your immigrant ancestor. Look for relatives also. Sources are rarely given so you may need to verify the information for yourself.

These are just a few suggestions for sources to help you identify the place of origin of your Irish immigrant ancestor. You can look in the Research Wiki on FamilySearch.org or elsewhere on the Internet for other suggestions, or you can let a professional genealogist search these and other sources for you.

In next month’s blog we will discuss Irish sources and how to access many of them through online databases.

Barbara

[1] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs