Introduction to DNA

5

5May

It is common for siblings to look alike, for children to look like their parents, etc. My siblings and I look so similar, it is joked that my parents had the same baby ten times. [1] It was the bane of our existence that my sister and I were mistaken for each other. This resemblance goes beyond immediate family. My great aunt reports looking like her grandmother—my great-great grandmother. A photo of one family member could easily be mistaken for another. A WWII draft registration for my great-great-grandfather reported that he had hazel eyes, an eye color I share with some of my siblings.

It is common for siblings to look alike, for children to look like their parents, etc. My siblings and I look so similar, it is joked that my parents had the same baby ten times. [1] It was the bane of our existence that my sister and I were mistaken for each other. This resemblance goes beyond immediate family. My great aunt reports looking like her grandmother—my great-great grandmother. A photo of one family member could easily be mistaken for another. A WWII draft registration for my great-great-grandfather reported that he had hazel eyes, an eye color I share with some of my siblings.

Where does this resemblance come from? My family and I share a lot of DNA with each other. My siblings and I each inherited about fifty percent of our DNA from each parent, and therefore a lot of our DNA is identical to each other. If we were to compare the specific DNA of all ten of my parents’ offspring, each of us would share a different fifty percent— with each other and with our parents. That fifty percent shared DNA is enough for us to look strikingly similar.

What is DNA?

DNA is the genetic code found within each of our cells. This code influences everything from our physical appearance to our mental health, diseases we are susceptible to, and how we age. It is useful for genealogy research since we are made up of large and small segments of our ancestors’ DNA.

Humans have twenty-three chromosome pairs in our DNA. The twenty-third chromosome is the one that determines biological gender; males have XY and females have XX. When a child is conceived, the chromosome pairs are split and recombined in each parent. For each chromosome pair received by the child, half will come from the father and half from the mother. This process of recombination is random.

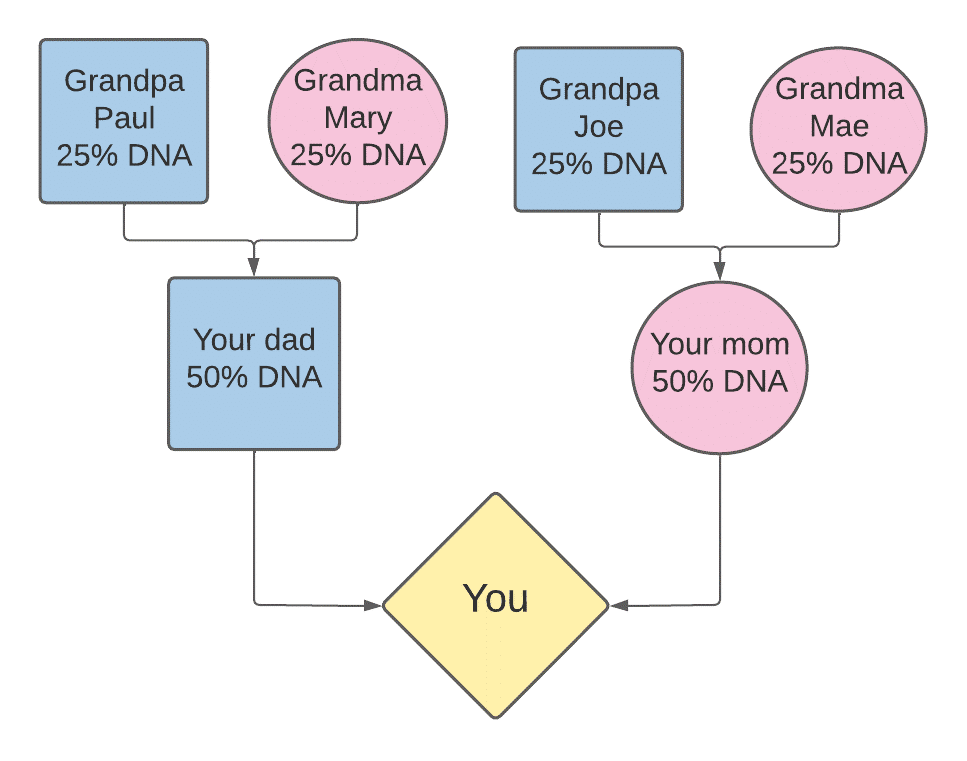

On average, an individual receives 50% of their DNA from each parent, about 25% from each grandparent, 12.5% from each great-grandparent, and 6.25% from each great-grandparent. These numbers are not exact due to the randomness of recombination.

Examining the following charts help us visualize the process. The first chart shows a three- generation pedigree, where you receive 50% of DNA from each parent and approximately 25% from each grandparent. [2] Each of your parents receives fifty percent of DNA from their parents, which they pass onto you.

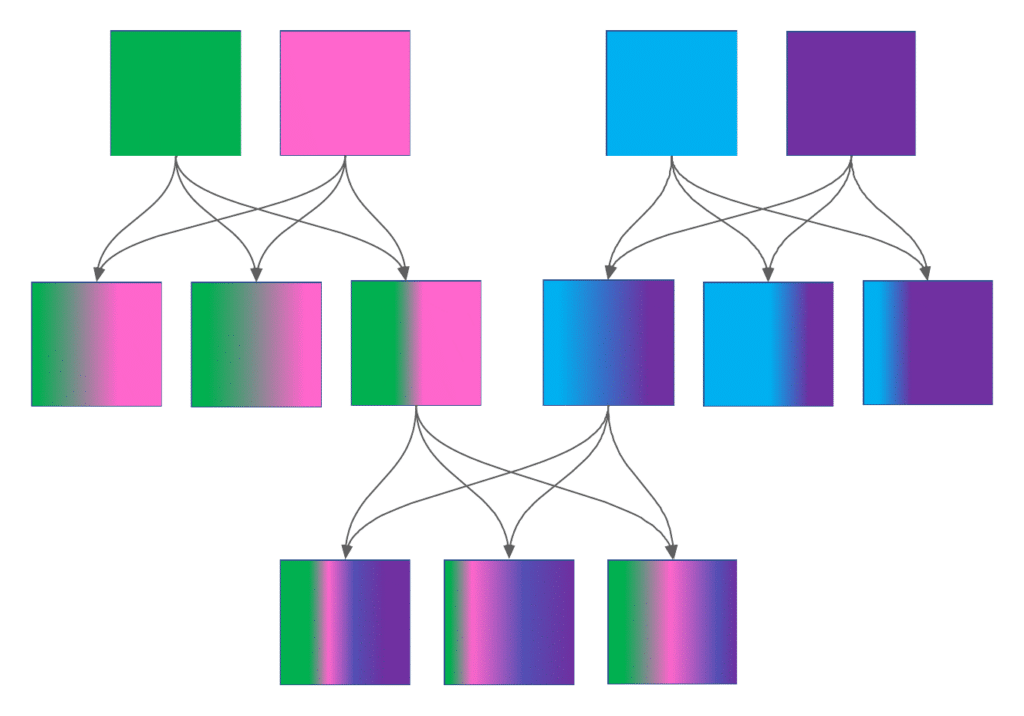

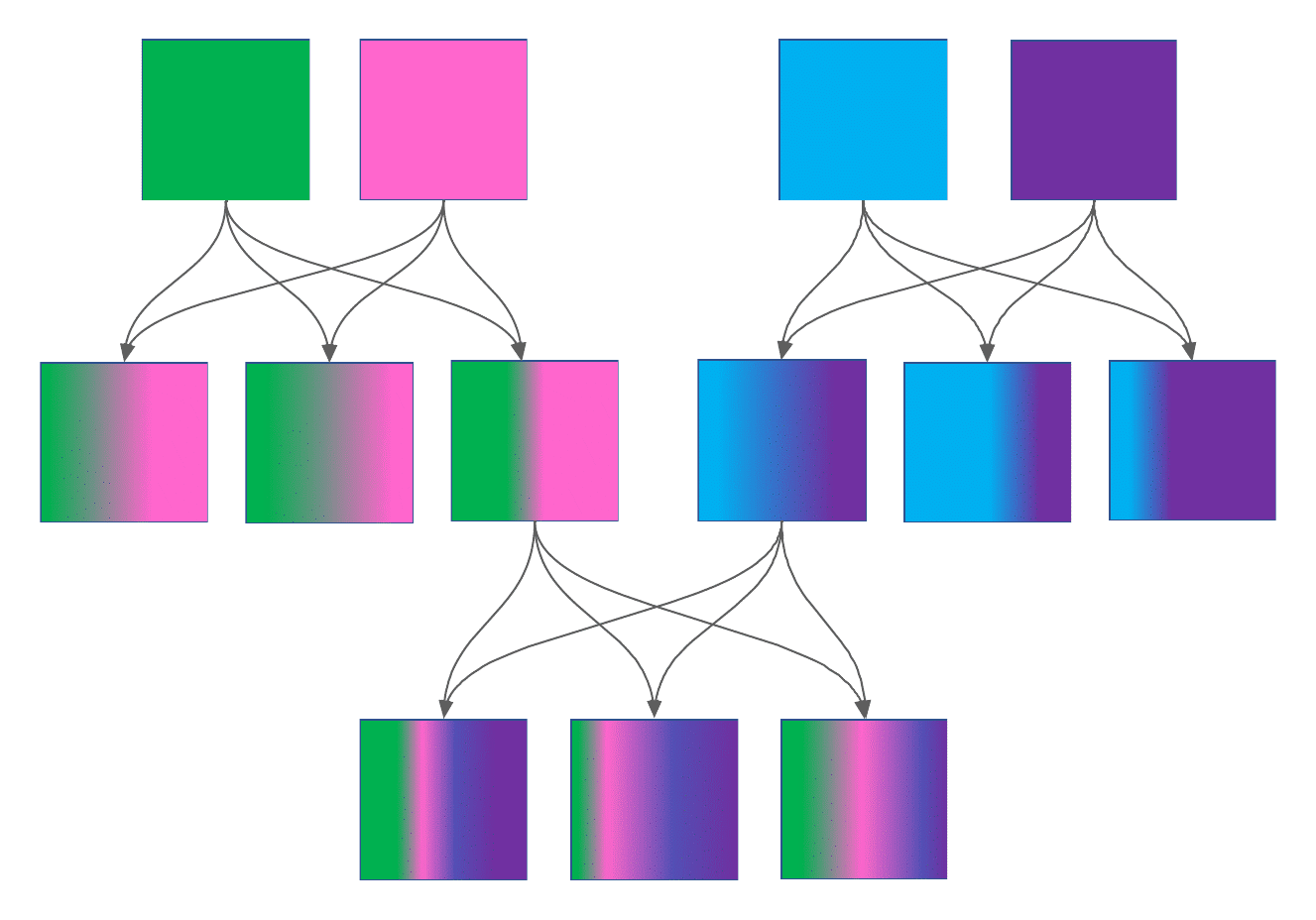

The next chart shows Mr. Green and Miss Pink having three children together.[3] Gradients are used to illustrate each child receiving different DNA from each parent. Mr. Blue and Miss Purple also married and had three children together. One of the Green-Pink children marries one of the Blue-Purple children, and they have three children together. By examining the chart, you can see how each of the offspring of the two couples inherited different DNA yet have a lot of similarities.

What does this mean for genealogy? The further back an ancestor is from you, the less DNA you have from them. For this reason, it is wise to test older relatives. Additionally, not all your third cousins will share DNA with you. The further back the most recent common ancestor, the less DNA you and your cousin each share with that ancestor. This means there is a lower possibility that you and said cousin inherited the same DNA from that ancestor. Because siblings inherited different portions of their parents’ DNA, they would have inherited DNA from different ancestors and have different sets of genetic cousins.

Types of tests

There are various DNA tests that can be used in genetic genealogy. Autosomal DNA (atDNA) tests the first 22 chromosomes, which are recombined as discussed above. This is the DNA you inherit from all your ancestors, more so from recent generations than from distant generations. Because half the DNA is lost at every recombination (every generation), this is helpful only as far back as 5-7 generations. This kind of DNA test also provides data of ethnic origins.

Y-DNA examines only the Y chromosome, which is passed from father to son. Because of this inheritance pattern, only biological males can take a Y-DNA test, and it will give information about the DNA inherited from the patrilineal line (father’s father’s father’s father, etc.). When using this test to test a particular ancestral line, you will need to trace the male line descendants of the ancestor in question. If one of the sons or grandsons only had daughters, that Y chromosome ended with him or daughtered out. Therefore, another line of descent must be traced. If every line daughtered out, go up a generation or two from the ancestor in question and trace a male line of descent from him.

In cultures where the surnames are passed down along the paternal line, the Y-DNA and surname are usually closely related. The surname along the patrilineal line usually changes in cases of adoption or illegitimacy.

Mitochondrial DNA (mDNA or mtDNA) is a ring of DNA separate from the chromosomes which is passed down unchanged from mother to child. Anyone can take this test to learn of their matrilineal line (mother’s mother’s mother’s mother, etc.). Even though sons inherit their mother’s mtDNA, they do not pass it on to their children. When finding a candidate for an mtDNA test, trace the female line down of the ancestor in question to a living descendant. The mtDNA ends when a mother only had sons.

Y-DNA and mitochondrial DNA are both passed down without recombination, so the only changes are mutations. Because they are virtually unchanged, they can be traced much further back than atDNA. Test results for both will indicate the genetic distance between cousin matches, or the number of mutations between the test taker and their DNA match. Test types will be further discussed in a future blog post.

How does DNA help in genealogy?

DNA research can help with solving brick walls and with confirming paper trail evidence. Sometimes the informant on a record was mistaken about our ancestors, and sometimes our ancestors themselves were mistaken about their families. In other cases, our ancestors may have intentionally falsified information on records. In essence, the paper trail can lie. But DNA does not lie. By correlating the paper trail and DNA evidence, we can gain a fuller picture of our ancestors’ lives. There are various ways that DNA can help in research, each of which deserves its own blog article, so we will be brief here.

First, we can make the most of DNA research by having our known living relatives test, especially the older generations as mentioned previously. Encourage your friends, associates, and neighbors to test as well. The more people who take DNA tests, the more people there are in the databases, the better the results. Once you have taken a DNA test, transfer your results to every database that will let you import results. This will also increase your pool of DNA matches.

DNA testing can be used to confirm relationships between ancestors. If you suspect two people are related, whether or not you have paper trail evidence of their relationship, trace descendants of each ancestor until you’ve identified candidates for DNA testing. Whether you are testing atDNA, Y-DNA, or mtDNA will determine who is eligible. When you get the test results, evaluate them, and see if the candidates share the expected amount of DNA.

DNA testing can also expose misattributed parentage, also known as non-paternal events (NPEs). This can result in not seeing the relatives you expected and seeing others who you may not know instead. By investigating, you can find out who the real parents were.

If one of your ancestors was an illegitimate child, DNA research can be conducted to find their father. By evaluating your matches to determine which common ancestor you inherited your shared DNA from, you can narrow down your matches to the ones whose common ancestor is the unknown father. Future blog posts will show this process in action.

Adoptees can use DNA testing to find their biological family. A male adoptee taking a Y-DNA test can get clues on what his birth surname was. An mtDNA test can help identify the maternal line. An atDNA test can be used to match cousins on both sides of the family. The adoptee can identify candidates for their parents through the common ancestors of their matches.

If you have not taken a DNA test, check out the different companies and purchase one. If you have taken one, start exploring the DNA results. What brick wall in your family tree would you like to apply DNA to? Whatever your research challenge needing DNA is, Price Genealogy can help you.

By Katie

Resources

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/dna-basics

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/foundations-in-dna-1-of-5-genealogy-and-dna/?category=dna&subcategory=dna1

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/foundations-in-dna-2-of-5-dna-overview/?category=dna&subcategory=dna1

- https://www.americanancestors.org/video-library/dna-consultations-american-ancestors

[1] Garner family photo, taken 2019 in Montgomery, AL; used with permission.

[2] Chart created by author

[3] Chart created by author