German Jewish Research – Part One

10

10Jul

Are you ready for an adventure of discovery? Tracing your German Jewish genealogy can be a challenging and exciting adventure. Changes in laws and politics, persecutions and pogroms have affected Jewish life and types of records kept through the ages. Jews have migrated within Europe and dispersed throughout the world. This first of two articles about German Jewish Research will provide an introduction and some resources to help you get started. Part Two will go into more detail about specific record types and additional resources.

Are you ready for an adventure of discovery? Tracing your German Jewish genealogy can be a challenging and exciting adventure. Changes in laws and politics, persecutions and pogroms have affected Jewish life and types of records kept through the ages. Jews have migrated within Europe and dispersed throughout the world. This first of two articles about German Jewish Research will provide an introduction and some resources to help you get started. Part Two will go into more detail about specific record types and additional resources.

German Jewish Genealogy Research

Ashkenazi and Sephardi – a brief overview

Ashkenazi refers to the Jews who first arrived in Germany during the Middle Ages.[1] They settled along the Rhine river in what was then the Holy Roman  Empire. The Jewish communities in the cities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz, known as the ShUM cities, formed the center of Jewish life. Persecutions, especially during the Black Death (1346-53) caused the Ashkenazi population to shift eastward to what is now Poland and beyond. Poland then became the cultural center of Jewish life.

Empire. The Jewish communities in the cities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz, known as the ShUM cities, formed the center of Jewish life. Persecutions, especially during the Black Death (1346-53) caused the Ashkenazi population to shift eastward to what is now Poland and beyond. Poland then became the cultural center of Jewish life.

Groups of Ashkenazi refugees from eastern Europe returned to various parts of Germany after the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). Some German rulers, e.g. the electors of Brandenburg and the Palatinate, seeking the Jews’ financial and commercial skills, invited and welcomed Jewish settlers to help develop their devastated lands.[2] Traditionally, the choice of occupations for Jews in Germany was very limited. Not allowed to practice a trade or craft, they commonly worked as moneylenders and peddlers.

Sephardi Jews included those who had settled in Spain and Portugal in biblical times. The 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain drove Sephardi to other parts of Europe and North Africa.[3] By the late 16th century they had arrived in the German city of Hamburg via the Netherlands.[4]

Jews in Hamburg – an example of complexities

During the 17th century, both Sephardi and Ashkenazi had settled in the city of Hamburg and neighboring towns.[5] However, they had different experiences.

Sephardi Jews were the first to arrive in Hamburg. They were able to remain in the city when some inhabitants wanted to expel them, because the city council recognized their economic benefit to the city. While they lived and worked in Hamburg, they continued to speak and write in their native languages (Spanish and Portuguese) for two more centuries.

At the beginning of the 17th century Ashkenazi Jews started to settle in Wandsbek and Altona, two suburbs of Hamburg which were under Danish rule at the time, as well as in the city of Hamburg itself. Jews fleeing persecution in Poland and Ukraine arrived in 1648.

Both Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews lived in Hamburg and its surroundings. They spoke different languages and were subjects of different nationalities (Hamburg/German and Danish). While the Sephardi enjoyed rights of citizenship in Hamburg, the Ashkenazi were expelled.

Some laws affecting Jewish research

Registration laws

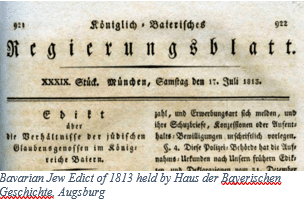

As Jews were granted varying degrees of civil rights and privileges, they started appearing in certain town records. For example, in Bavaria, Juden-Matrikel, civil registers of Jews within a given town, were created as a result of the Bavarian Jewish Edict of 1813.[6] This edict granted civil rights to Jews and allowed them to acquire property, on condition of being entered into a register. These Jewish registers included names and family relationships, as well as how they earned a living.

As Jews were granted varying degrees of civil rights and privileges, they started appearing in certain town records. For example, in Bavaria, Juden-Matrikel, civil registers of Jews within a given town, were created as a result of the Bavarian Jewish Edict of 1813.[6] This edict granted civil rights to Jews and allowed them to acquire property, on condition of being entered into a register. These Jewish registers included names and family relationships, as well as how they earned a living.

Each community had a limited number of register numbers, thus limiting the number of Jewish families in a given location. Their choice of a place of residence and doing business was now regulated, as was the decision to be married, since an authorized marriage approval had to be obtained. If Jews did not meet or chose not to agree to the requirements associated with being registered, they were treated as foreigners. If all the register numbers were allotted, Jews seeking to establish a household in town were essentially forced to emigrate to another town with openings or to a different state or country.

Generally, in German research, when you locate records in the town of origin, you can easily trace several generations of a family, since they usually lived in the same place for several generations. However, German Jewish researchers may not have the same experience, depending on the time period. Understanding these types of laws will also help you understand why someone may not be found in an expected record.

Required surnames

Jewish hereditary surnames evolved over time, generally in response to the customs or laws of the area of residence. Sephardi hereditary surnames were influenced by Arab customs, dating back to the 1500s.[7] However, Ashkenazi did not begin to use hereditary surnames until the early 1800s, when they were required by law in individual German states and other European countries. Beginning in 1790, individual states in Germany started requiring fixed surnames. Learn more about Jewish Surnames in the FamilySearch wiki article “Jewish Names Personal.”

Getting started with German Jewish Genealogy Research

- Start with what you know. Review documents you have at home. Gather information from relatives.

- Determine ancestor’s town of origin. The research approach you take will depend on the country in which you will be conducting research, so in this case it would be Germany. Critical to German research is knowing the ancestor’s town of origin. The following previous blogs can help you identify a town of origin: Three steps in finding a European ancestor’s town of birth, Finding German Immigrant Town of Origin Parts I and II.

- See if others are researching the same line. With a known surname and town, check JewishGen Family Finder (JGFF) to find others who may be researching the same family line. JewishGen.org requires free registration. JGFF is one of many databases, including the JewishGen German Collection, offered by JewishGen.org to aid in Jewish genealogical research.

- Learn about local history and laws. Historically, the German region consisted of hundreds of principalities and states, each with their own independent laws. Understanding the history and local laws in your ancestor’s specific town and state will help you in your research.

- Wiki pages are great sources of information. One example, the FamilySearch wiki page “Jewish History” includes key dates and refers to some laws of interest to genealogists.

- The Jewish Virtual Library provides a general history in their Germany Virtual Jewish History Tour. It also includes links to information about individual states and cities in Germany Cities Virtual Jewish History Tour.

This concludes part one of the two-part series on German Jewish Genealogy Research. Part Two will go into more detail about specific record types and additional resources.

Researchers at Price Genealogy are available to help you along your adventure of discovery. We have professionals who can assist us with on-site research worldwide.

Gina

[1] Wikipedia (www.en.wikipedia.org), “History of the Jews in Germany,” rev. 20:37, 28 June 2020. Wikipedia, “Ashkenazi Jews,” rev. 00:44, 27 June 2020.

[2] Magda Teter, “Early Modern Jewish History: Overview,” Wesleyan University, Early Modern Jewish History (www.jewishhistory.research.wesleyan.edu : 2008), German Lands. Direct link: http://jewishhistory.research.wesleyan.edu/i-jewish-population/4-jews-of-the-holy-roman-empire/a-german-lands/

[3] FamilySearch Wiki (www.familysearch.org/wiki), “Jewish History,” rev. 08:14, 12 March 2018.

[4] Zvi Avneri and Stefan Rohrbacher, ed., “Germany: Hamburg,” American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise, Jewish Virtual Library (www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org : October 2014); citing Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd Edition. Direct link: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/hamburg

[5] Ibid.

[6] Wikipedia (www.de.wikipedia.org), “Bayerisches Judenedikt von 1813,” rev. 16:04, 2 December 2019.

[7] FamilySearch Wiki (www.familysearch.org/wiki), “Jewish Names Personal,” rev. 09:21, 5 May 2020.

Do you have any further questions about German Jewish genealogy work? Let us know in a comment below!