France Genealogy Research – Part One

21

21Feb

If you have French ancestry, you may be a little nervous about starting research and unsure as to where to begin. Is the name you are researching even French? Will you have to go to France to find the records? Maybe it is the language that is stopping you. You do not know the French language, so how are you going to read the documents? What if you do not know where in France your ancestors lived? You have the name of the town, now what do you do? These are just a few questions that you might have when first starting France research. Worry no more, France has excellent genealogical records. Let’s calm your worries about French genealogy records and get you to a place where you feel that “you can do this!”

FRENCH GENEALOGY RECORDS

NAMES IN FRANCE

When doing research in France, it is useful to know the various changes that took place with regard to names, given and surname. Below is a partial list noting some of those changes.[1]

- Generally, before the 1200s, individuals had only one given name. As the population became larger, it became essential to differentiate between persons with the same name. Often family names developed from a variety of sources.

- Names of saints or persons from the Bible, such as Samuel or Luke.

- Occupational names based on the person’s trade, such as butcher (Boucher).

- Descriptive nicknames, such as LeBlanc (blonde hair or fair complexion).

- Geographical names based on a person’s residence, such as forêt (forest…Dubois).

- As of 1539, the surname was required to be written next to the baptismal name in the registers. In the 1700s, names were written various ways in the same document. By 1808, particularly in civil registration, the spelling of surnames became fixed, however, slight variations in spelling were still observed until 1877 when the first Livrets de famille [family record books] were issued.

- Throughout France, since about the sixteenth century and into the beginning of the nineteenth century, adult females have retained their birth names after marriage on all legal documents.

- Quite often, children were given more than one given name, which may be names of parents or relatives. Baptismal names may be different from the names given in civil registration or may have been omitted later in the child’s life. Others were changed to the most common way that it was spelled during the time period that was being written. Many given names were given dialectical variations and forms, for example, Daniel may also be found as Denic or Deniel.

- Compound given names, such as Jean-Luc, Jean-Paul, or Anne-Sophie are not uncommon. These are not considered to be two separate given names. The second part of a compound name may be a given name normally used by the opposite sex. However, the gender of the compound is determined by the first component.

If you are wondering if your ancestor’s surname is French, a quick way to check is to go to Geneanet.org and type in the name. If your name does not come up, chances are that it may not be French. This site is a paid site. Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints can receive a free membership by following the link https://www.familysearch.org/campaign/partneraccess/. You must be logged into FamilySearch to verify your Church Membership.

Another site to check for surnames is Géopatronyme.com. The site is free and if your ancestor was a person with a unique name, you may be able to find the department from which he or she probably came. It covers the surname distribution in France from 1891-1990.

Try to get the earliest form of your ancestor’s surname, before it was Anglicized. If there were many spellings, try to get them all. Variations can indicate the true pronunciation, which could lead to a location.

Find both the given names and surname, as well as any middle names they may have. Try to learn the name used in the country of origin and any variations of it. Nominis (https://nominis.cef.fr/) is a site that lists the names of Saints and gives definitions, origins of names, region of origin, etc.

WHERE TO START

Start here if you have the following: the name of your French ancestor and place and date of birth, marriage or death.

Depending on the date, your search will take you to three different types of archives: after 1900 or 1910, you will need to write to the town’s city hall (mairie); between 1793 and 1900s, you will be looking at civil registration (état civil) and should go online to the department (Archive Départementale) where your ancestor lived; before 1793, you will be seeking parish records (registres pariossiaux). Most of these can also be found online.

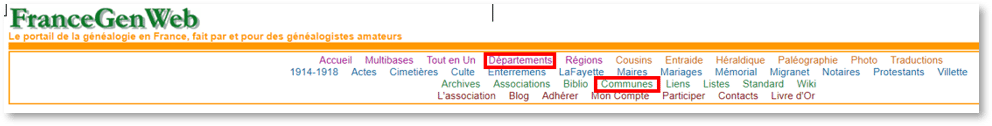

Knowing the place, you need to find which department the town is located in. A quick way to find the department is to just type the name of the town into Google or Wikipedia. From there, you can go to the department. If the town does not come up, you can type the name into the Commune section on FranceGenWeb and it will tell you which department(s) the town is located. Below is what the main page of FranceGenWeb looks like.

As you can see, there are many categories other than Commune to search. Once you find the town listed, you can find the department by clicking on Départements (on this same page). From there, you will find a map of France. Click on the department and follow the links to the online records (archives en ligne). If you do not know the number corresponding to the department, they are listed right below the map.

If you still cannot find the place, type your ancestor’s name and date of birth into Filae.com (also a paid site) and/or Geneanet. Both sites are quite useful in finding the name of the department for a specific town.

Once you are in the departmental archives, the records are organized by town. With a name, date and place, you can then access the records online for that specific time period.

Look here if you know the name of your French ancestor and place of birth, marriage, or death, but you do not have a date.

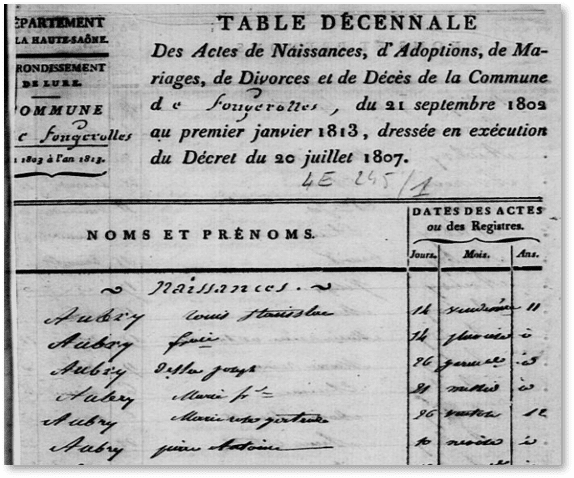

To find the date, you can check the 10-year tables (tables décennales) where the town was located. So, for example, say your ancestor was born in Fougerolles, France. The town of Fougerolles is located in the Department of Haute-Saône, so you will look for the record(s) in the archives of Haute-Saône (http://archives.haute-saone.fr/).

The 10-year tables list all births, deaths, and marriages in alphabetical order for a 10-year period for each town. They will be located in the civil registration records and began in 1792. Use them to determine if your ancestor’s record is in a commune or town before you try and find the actual record. Looking up names in the tables will also give you clues for relatives living in the same commune. Below is an example of what a 10-year table for births looks like.

Your research should start here if you have the name of your French ancestor and date of birth, marriage, or death, but you do not know where they were born.

When you do not know the place where your ancestor was born, you should do as much research in the country where they immigrated to. Sources most likely to indicate the place of birth or last residence before immigration include living relatives, family stories, papers, photos, vital records, passenger lists, naturalization records and newspapers (obituaries), county histories, and compiled biographies. You may also find that church records are especially helpful. France is an overwhelmingly Catholic country, and U.S. Roman Catholic records may refer to the immigrant’s parish in France.

You may also look on the site Géopatronyme to find a location. It lists the departments and communes where a surname is most prevalent. People do not move around, so your ancestor’s surname may be there.

Filae has been indexing 19th century records from all departments, so if you are looking for a record for which you do not know the exact place and date, it is a good place to look. The indexed records can be very helpful; however, they are not complete.

Also, a good place to find a location is Geneanet. It has a huge database of family trees, and various indexed records, uploaded by users. It is, by far, the most popular genealogy website in France.

Now that you have some ideas on how to get started researching your French ancestors, you see that it is not so scary. Remember, the more research you do, the better you will be at it, and in time you will see how much fun research really is.

This is part one of a two-part series on France genealogy research. Part two is a listing of many online resources that can help you with France research. As you go through the various sites and guides you will gain a better understanding and become more comfortable with French documents.

The researchers at Price Genealogy can help you discover your French ancestors.

Stacy

[1] "France Names, Personal," FamilySearch Wiki, accessed February 2020, https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/France_Names,_Personal; Heather Rose Jones, "Given Names from Brittany, 1384-1600," The Academy of Saint Gabriel, 2001, accessed February 2020, https://www.sgabriel.org/names/tangwystyl/latebreton/#articlecite; "French Name," Wikipedia, accessed February 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_name.

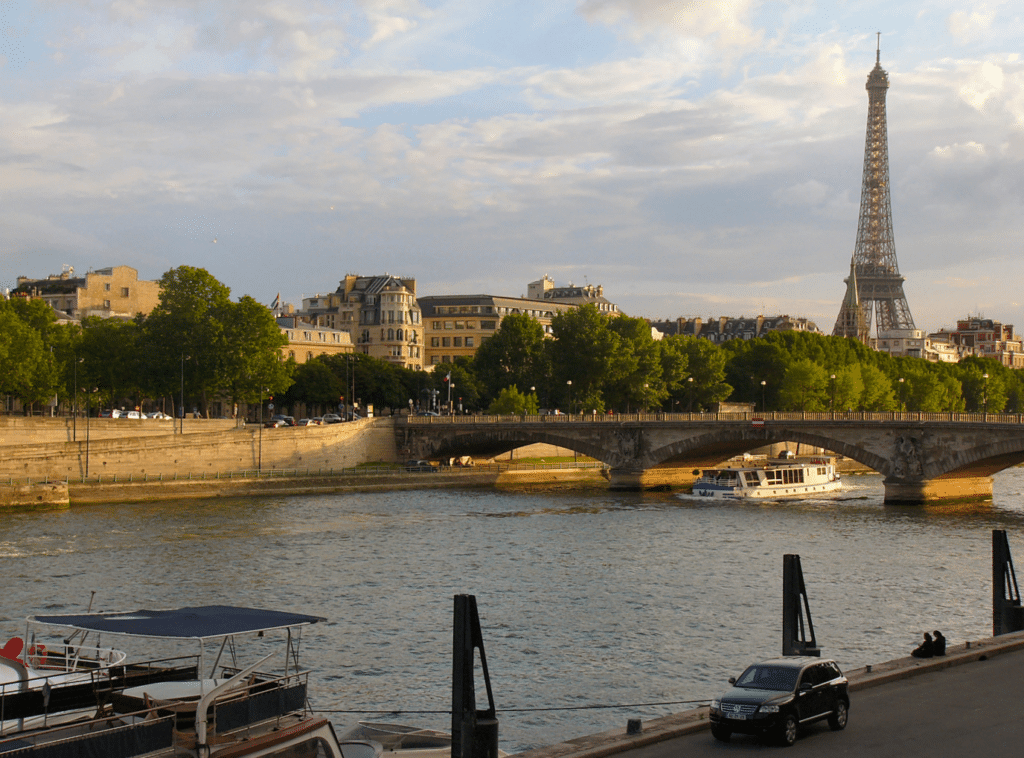

Photo: Skyguy414 at English Wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Have you had to search for ancestry information in French genealogy records? What was your experience like? Let us know in a comment below!