Find Your Irish Place of Origin

18

18Mar

Every March 17th it seems all of America is proud to proclaim their Irish heritage, with “Kiss Me, I’m Irish” shirts, a pint of beer with friends, parades, green food, and wee lads and lassies pinching schoolmates for not wearing green. Perhaps this year you want to find out more about your Irish ancestors. Be careful jumping into Irish records too soon if you only know a name. First you should try to discover any of the following: 1) the county of origin, and even perhaps a parish or townland; 2) names of family members; 3) neighbors or friends with whom they emigrated or settled near; 4) approximate time period of immigration; 5) any other identifying details such as birth date, marriage date, occupation, religion, or financial status. The more information you can learn about your immigrant ancestor, the greater chance of finding (and proving) them in Irish records.

Step 1: FAMILY RECORDS

Always start with what you know and work backwards from there. What family records or artifacts do you have that may tell you a place of origin? These might include journals, letters and envelopes, pictures, personal memories or histories, clothing, a Family Bible, and even oral tradition. Look through items you have inherited from older generations. Next, reach out to family members to ask them what family documents they have inherited. Make use of social media or DNA websites to connect with extended family members. And always check published family trees on websites like Ancestry and FamilySearch. Both websites allow documents to be uploaded to the tree, which may include family heirloom documents not inherited by your side of the family.

Step 2: HISTORICAL RECORDS

The next step is doing your own original research in the country of settlement. Start with records surrounding the ancestors DEATH. Obituaries may not only tell you place of origin but also include a life sketch. Death certificates should also be obtained, especially if your ancestor died after state certificates began to be issued, which recorded place of birth. Headstones may provide very little or a lot of information and should always be viewed when they exist.

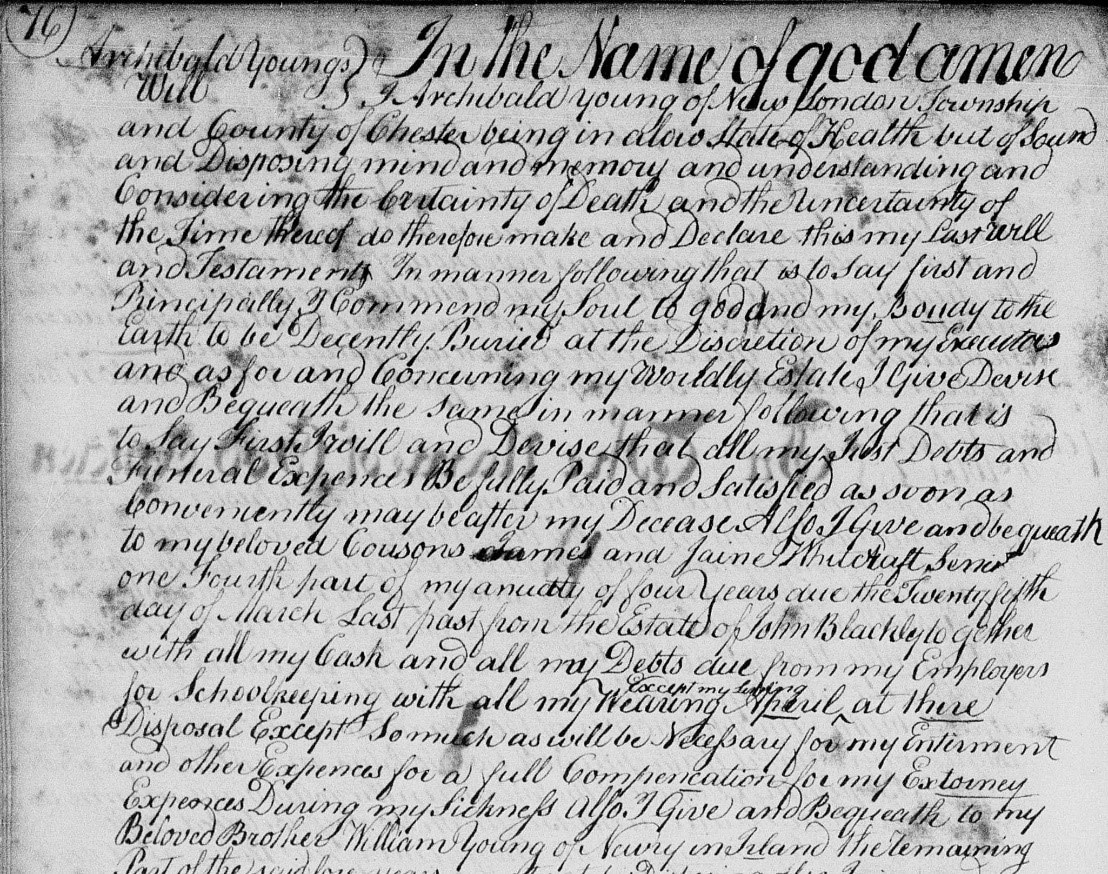

It is likely the immigrant ancestor still had family or close friends back in Ireland, and they may have mentioned them in their PROBATE RECORD if they left a will. Such was the case with Archibald Young, of New London Township in Chester County, Pennsylvania. His will was probated on June 13, 1782, in which he mentions his brother William Young of Newry in Ireland.

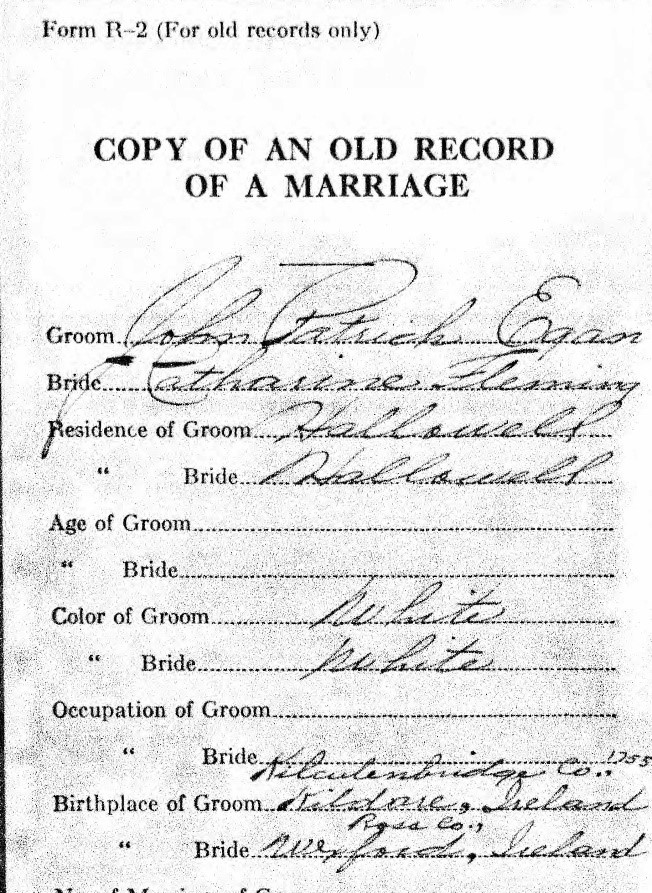

MARRIAGE RECORDS may occasionally list a place of origin, such as in the 1779 marriage record for John Patrick Egan and Catharine Fleming in Hallowell, Maine. The groom is listed as being from Kilculenbridge in County Kildaire, Ireland, and the bride is from Ross in County Wexford, Ireland.

PASSENGER LISTS may list more than just a country of origin. Mary Doherty, a housewife, and her daughter, Delia, who was only a few months old, are recorded on a 1925 passenger list from Londonderry, Ireland, on the ship Cameronian. Delia’s last permanent residence is recorded as Donegal, Ireland. Her nearest relative in Ireland was her grandmother, Mrs. Madge Gallagher of Meenarain, Dungloe, in County Donegal.

NATURALIZATION was the process in which an immigrant officially renounced their allegiance to a prior government and officially became a citizen of the United States. It was a court process that took a number of years. In 1842, Peter Conroy petitioned to become a naturalized citizen in the circuit court of New Orleans. He testified that he immigrated to New Orleans on November 25th 1826, and that he filed his Declaration of Intention in 1838, proving he had resided in the state for at least five years, which was the law at the time. When asked for his birthplace, he listed “the town of Carrick on Shannon, Ireland,” which was in County Leitrim.

CENSUS RECORDS generally only give the country of origin; however, sometimes more information is provided. Make sure you locate your ancestor, and all their known family members, in every census year in which they were alive. One of them may have listed a specific place within Ireland.

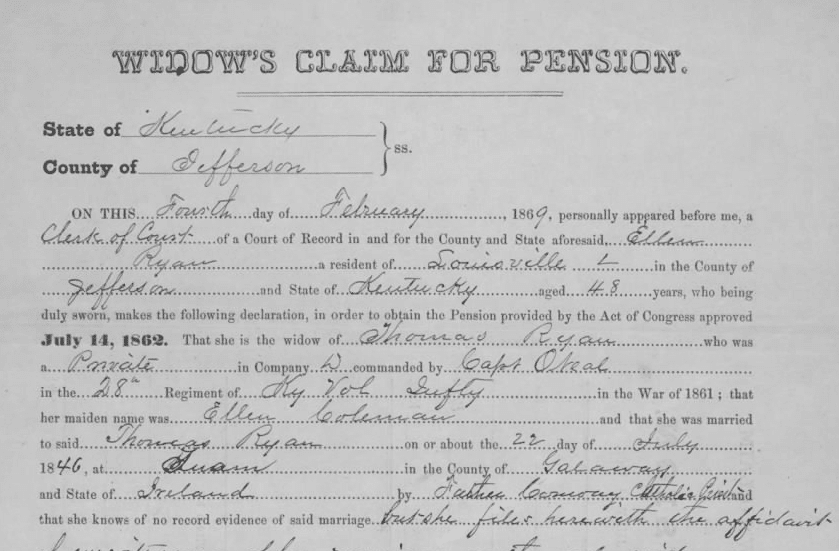

Don’t overlook MILITARY RECORDS. If you’re looking at 20th century ancestors, most men had to fill out a draft registration card, like the World War II Draft Registration for Michael Gormelly of Louisville, Kentucky, age 60, who was born in County Galway, Ireland, on Oct 12th 1881. You may also be surprised to find a Civil War Widow’s Pension. On February 4th, 1869, Ellen Ryan, the widow of Thomas Ryan, appeared before the court to obtain a pension. To qualify, she had to prove she was married to the soldier, so marriage information was requested. We learn that Ellen, maiden name Coleman, was married to Thomas Ryan on or about the 22 day of July 1846 at Tuam in the County of Galway, and State of Ireland, by Father Conway, Catholic Priest. With a date, county, and religion, a marriage record could then be sought for this couple in County Galway.

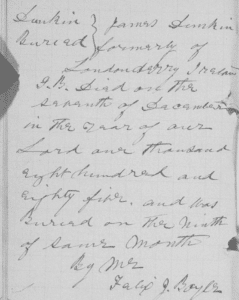

If you find a reference to a religion, you should check CHURCH REGISTERS where they settled.  An Anglican church burial record in 1885 for one of my ancestors in Frampton, Quebec, stated that James Dunkin was formerly of Londonderry, Ireland. Gillespie McLaughlin, George Dunkin, and Thomas Smyth were witnesses, and also ancestral family members. Don’t ever dismiss the names of witnesses. If you have early Latter-day Saint ancestry, check Branch records, Patriarchal Blessing index, and the LDS Missionary Registers. In this last source, we learned that John Tobin, son of Thomas and Ellen McGrath Tobin, was born 24 Oct 1835 in Dungarvan, Waterford, Ireland, and baptized into the church in March 1854. He was called to serve his mission to England, was set apart 25 Apr 1860 by Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt, but in the column recording his return date it says he was “cut off for adultery.” If you were researching John Tobin, you would want to check for illegitimate children in England!

An Anglican church burial record in 1885 for one of my ancestors in Frampton, Quebec, stated that James Dunkin was formerly of Londonderry, Ireland. Gillespie McLaughlin, George Dunkin, and Thomas Smyth were witnesses, and also ancestral family members. Don’t ever dismiss the names of witnesses. If you have early Latter-day Saint ancestry, check Branch records, Patriarchal Blessing index, and the LDS Missionary Registers. In this last source, we learned that John Tobin, son of Thomas and Ellen McGrath Tobin, was born 24 Oct 1835 in Dungarvan, Waterford, Ireland, and baptized into the church in March 1854. He was called to serve his mission to England, was set apart 25 Apr 1860 by Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt, but in the column recording his return date it says he was “cut off for adultery.” If you were researching John Tobin, you would want to check for illegitimate children in England!

Step 3: MIGRATION PATTERNS

By narrowing down the time period your Irish ancestor immigrated to their country of settlement, you can research common migration patterns of the period. In America, between 1820 and 1860, over one third of all immigrants were Irish, and in the 1840s – during the Famine years – it may have been nearly half! Another large wave of Irish immigration was the Scots-Irish in the late 18th century. Much of Eastern Canada, the lower Mid-west, and Southern United States was settled by the Irish and Scots-Irish. Scots-Irish and Germans were the first to use the Wilderness Road in large numbers. Others came down the Ohio River. Large settlements crept up along these migratory routes, so learn the navigation routes and trails being used when your ancestor traveled.

Step 4: CAST A WIDER NET

When you’ve done all you can on your immigrant ancestor, refocus your efforts on his or her non-direct line children and their children. It may also be necessary to branch out to neighbors. Some immigrants migrated with neighbors or a religious community. Read church, town and county histories, including biographies of prominent settlers. Determine if the majority of settlers in one area came from the same county or town in Ireland. Make note of witnesses or probate executors, administrators, or bondsmen. Be aware of who your ancestor is buying land from and selling it to. Check court records for interactions they had with neighbors. Look at place names – do they share a common placename with the early settlers’ origins? For example, the city of Limerick outside of Louisville, Kentucky, was settled by Irish emigrants, almost all of whom were from the Irish county of Limerick.

Finding that place of origin is one of the hardest walls to break and some take years of research to figure out, so you may need to settle in and get comfortable! May you have the Luck o’ the Irish with you as you endeavor to uncover your Irish immigrant origins.

If you need help researching your Irish immigrant ancestors Price Genealogy can help.

By Emily

[Works Cited]

Library of Congress, Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: Irish-Catholic Immigration to America (https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/irish/irish-catholic-immigration-to-america/#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%20as,all%20immigrants%20to%20this%20nation.: accessed 17 January 2022).

FamilySearch Wiki contributors, “Ireland Finding Town of Origin,” FamilySearch Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Ireland_Finding_Town_of_Origin: accessed 17 January 2022).

Photo: National Library of Ireland on The Commons, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quintin_Castle,_County_Down,_Ireland_-_Up_in_Down%3F.jpg