Are You Descended from English Gentry, Nobility, or Royalty – Part 2

15

15Feb

When people get into tracing English gentry and royal lines, they will see themselves as part of thousands of years of human history. It beckons you into another world . . . pedigrees of opulent aristocrats going back 1,000 years, many of whom lived on a grand scale in palatial houses; the names of people that fill the history books; men and women who set the social fabric and mores of their culture . . . a powerful ruling elite supported by layers and layers of people of lesser rank, right down to the agricultural laborers on their estates. Some pedigrees include descents from deities or gods themselves. It shows how our ancestors thought. It’s all truly amazing . . . but also so fanciful at the same time.

Many characteristics of landed gentry in the part 1 blog can also be applied to titled nobility, but for nobility, it was on a much grander scale. A major difference is that members of the peerage held their titles in hereditary perpetuity. Of course, there were penniless and wastrel aristocrats, but also, men of humble origins who rose to the top of society. Many topics that were discussed in relation to landed gentry also apply to the peerage: primogeniture, dynastic strategies, downward social mobility for younger sons and daughters, etc. Marriage settlements and family settlements, entailments, and marriage alliances were common among all landowning people, from the prosperous yeomanry and lesser gentry, right up to the aristocracy. Also, many of the sources mentioned in the landed gentry blog apply to the nobility. There are additional sources at the end of this article.

English Gentry

Who were the nobility? The Peerage, from highest to lowest rank, are dukes, marquess, earls, viscounts, and barons. A common title of nobility that is not considered to be part of the peerage is baronet. They are Commoners of the lesser nobility. King James I raised funds from those desirous of paying for the honor. About 2,000 English families comprise the Peerage and Baronetage. All of these are hereditary, though by the end of the 20th century, Life Peers were being created whose title was not passed down. Much of the land across England was controlled by the peerage, baronets and the upper gentry. If your ancestors were sub-tenants of these aristocrats, it is very likely that some of the documentary evidence on your family may only survive among the muniments still held by these families. The muniments were often at the principal “seat” or home of the nobleman, often far from the lands that your ancestor held by lease. To learn the name of the person that owned the land that your people farmed, search deed collections in record offices or read the various county histories. Tax records like Land Tax Assessments or the Tithe Apportionment also tell who owned the land.

Recognizing Noble Ancestors

Anthony Adolph’s book, Tracing Your Aristocratic Ancestors (2013) provides richness and depth to this topic and is well-worth reading.

Consider how stories may have come down in your family. Some ancestors come from an illegitimacy, and it is common to find stories explaining how it happened: an affair by the younger son of an earl with one of his servant girls, or an elopement between people of unequal status was common. Stories may have come down in your family of lost wealth, bankruptcy, or alienation of a son from his noble father, or his pursuit of a more adventurous lifestyle. Sometimes your ancestors may have worked in a nobleman’s household, so pay attention to the proximity of your people to those around them. If your ancestor is mentioned in a prominent person’s will, or was set up as the recipient of a trust, this is worth pursuing. Wealthy benefactors may have had their unstated reasons for bestowing legacies on someone.

The first place to look for noble antecedents are surnames that are known to be held by the nobility. But, sometimes the wealthiest of your ancestors don’t have lines that can be traced to people of ever-increasing status each generation. There were a lot of people that the French called the nouveaux riches or the newly rich. Because of commercial or industrial wealth, they perhaps had far more money than the old stock aristocrats that may have only had a title and very little money behind it. The fortunes of families were always rising and falling. Mr. Adolph tells the unlikely tale of how Kate Middleton’s (the Duchess of Cambridge, wife of Prince William) father’s prominent line cannot be proven back to royalty, but her mother’s coal mining ancestors can. It turns out that an eighteenth-century baronet wasted his wealth and ended up in a workhouse.

But, beware, there were lots of sycophants and wannabes who tried to emulate the rich and famous, but their pretensions and aristocratic airs and over-wrought lifestyle often masked more humble origins. Many a wannabe aristocratic or suddenly rich merchant altered his pedigree to show deep descent from prominent families. Coats of arms were often used illegally by people who had no right to display them as their own. There are many online purveyors of heraldic shields and crests that have no connection to your actual ancestors.

Heraldry, Visitations, and Improving Standards

A genuine coat of arms in your family could be indicative of noble connections. The College of Arms in London regulated the granting and updating of arms and pedigrees. Arms were granted to individuals, not to families, so each younger son had to go to the Herald’s office to register his arms with a distinct mark of cadency that would distinguish him from his father. In the case of heiresses, or co-heiresses, the arms of a man and woman might be impaled together on the shield. There are lots of ways to research arms, crests, mottos, or the blazons (description in words) of arms, and it is a near-science that can require much study. You can write the College of Arms to see if they can help you, but don’t expect it to be cheap.

Some of the material held by the College of Arms has been published, particularly by the Harleian Society. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Heralds toured England checking on those who claimed a right to bear arms. They would record the armiger’s arms and pedigree. These so-called Visitations have largely been published, and sometimes manuscript copies can be found at the British Library. But it is important to remember that the visitation pedigrees and arms were not intended for the titled nobility, who had to register every change directly with the Herald’s office. The visitations are, however, one of the best ways to discover how a gentry family may be related to nobility and ultimately to royalty.

Many titles have not survived in the male line and have become either dormant, abeyant or extinct. Some people go to great effort to try to establish their claim to a dormant or abeyant title.

A few years after the end of the Herald’s Visitations in the 1680s, early peerage publications appeared, and not only were they a place for prominent families to be featured, but it was a means for people who were interested in making claims to old titles to do so. Within a few decades, many of these publications arose, but Burke’s ultimately became the best known. Early editions of Burke’s were full of mythical origins of families. Many noble and gentry families claimed descent from Companions of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. By the nineteenth century, the great genealogist Horace Round demonstrated how fanciful these claims to 1066 and other heroic origins were, and he inaugurated a new era of scholarly genealogical studies. In the later twentieth century, Anthony Camp continued with this exacting scholarship and documented the origins of many early lineages. He wrote My Ancestors Came With the Conqueror: Those Who Did and Those Who Probably Did Not (1990).

Medieval Noble lines and Royal Pedigrees

Once you have connected with the upper gentry and with the titled nobility, a large number of those pedigrees ultimately connect with royal lines, often through a female line. One cannot assume that their direct male line can be traced right back to the Norman invaders of 1066 or to the earlier English or Anglo-Saxons, as was believed for so long. Much scholarship has gone into these early lines. Sir Anthony Wagner, Garter King of Arms, in this regard achieved seminal works with his English Genealogy (1983) and Pedigree and Progress (1975), and Anthony Adolph in Tracing Your Aristocratic Ancestors (2013) has summarized so much of this in a popular form.

Probably the quickest way to see some of the surnames that descend from Anglo-Norman and Anglo-Saxon lines is on the FamilySearch Wiki, “England Pre-Norman Conquest Surnames (National Institute).” Wagner quoted earlier scholars from the 1950s who said that there were about 300 surnames that could be traced back to their place of origin in Normandy, France. There were of course many others from this early period that were French but for which no specific place has been found. The Wiki page lists only the nineteen men who were proven to be with William at Hasting, out of what must have been an army of thousands. Prominent surnames included Mowbray, Montfort, Beaumont, Mortian, Giffard, Warrenne, Malet, etc. William Mallet is the only 1066 Companion for whom there is a lineal descent in the male line to nowadays. There are numerous descendants from later Norman invaders through junior or cadet lines and through daughters.

Probably the quickest way to see some of the surnames that descend from Anglo-Norman and Anglo-Saxon lines is on the FamilySearch Wiki, “England Pre-Norman Conquest Surnames (National Institute).” Wagner quoted earlier scholars from the 1950s who said that there were about 300 surnames that could be traced back to their place of origin in Normandy, France. There were of course many others from this early period that were French but for which no specific place has been found. The Wiki page lists only the nineteen men who were proven to be with William at Hasting, out of what must have been an army of thousands. Prominent surnames included Mowbray, Montfort, Beaumont, Mortian, Giffard, Warrenne, Malet, etc. William Mallet is the only 1066 Companion for whom there is a lineal descent in the male line to nowadays. There are numerous descendants from later Norman invaders through junior or cadet lines and through daughters.

The lands of about 4,000 Anglo-Saxon thegns were assumed by about two hundred barons who William the Conqueror divided England among. Wagner has identified only two ancient English families that can trace their male line back to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms before 1066. These are Arden and Berkeley.

If you are related to a titled family by 1500, you are probably descended from most of the earlier noble land-owning families going back to Anglo-Saxon England and to Normandy. The conquerors often married the daughters of the vanquished to give their rule greater authority. The male heirs of the defeated families would usually be killed off to prevent uprisings.

Kings of the Plantagenet dynasty ruled England from 1154 to 1485, and most of the prominent noble families of the later Middle Ages descended from them. Once you connect to the royal dynasties, you will quickly find yourself related to just about every important ruler back for at least another thousand years. The royalty of England were intermarried with the princely and noble families across Europe. In a sense, the history of Europe flows through your veins from the mythological past right up to you!

Wagner, Adolph, and others like Sir Iain Moncrieffe in his Royal Highness: Ancestry of the Royal Child (1982), were particularly interested in the widespread connections that medieval English royalty had across the European continent, and into deep antiquity. Christian Settipani has shown that there was continuity, even genealogical links, between the rulers of the late Roman Empire and the “barbarian” Germanic tribes that supplanted Roman rule in western Europe.

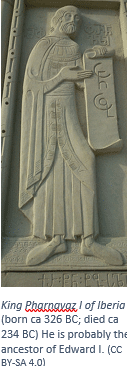

It is a huge subject, but if you are interested in the maximum extent that kingly pedigrees can be traced back into antiquity, Anthony Wagner’s chapter “Bridges to Antiquity” in his Pedigree and Progress book is very tantalizing. His accompanying charts show descent from various counts, dukes and barons of a thousand years ago, to the Viking dynasties and Frankish, Germanic, and Saxon tribes. Also, the charts include your distant ancestors Alfred the Great, Charlemagne, the Carolingians, Merovingians, Byzantine emperors, and then back through Georgian and Armenian rulers of 2,000 years ago to the earliest likely ancestors of King Edward I (1239-1307) of England. It is very likely that all people of English descent would find King Edward I among their ancestors, probably in many places due to extensive intermarriage. This powerful king, sometimes called the “Hammer of the Scots,” has had his princely lineage traced through contemporary records and with the prosopography method back through Byzantine emperors, to kings of Armenia, all the way to King Pharnavaz I, King of Iberia (in what is now eastern Georgia), who ruled from about 299 B.C. to 234 B.C. Wagner’s charts include ancient genealogies of Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Roman emperors of the A.D. 300s, Angles, Saxon, Jutes, the Caesars, Macedonia, the Ptolemies of Egypt, Judaea, and the kings of Syria, Lydia, Babylon, and Persia. It is all rather magnificent!

traced back into antiquity, Anthony Wagner’s chapter “Bridges to Antiquity” in his Pedigree and Progress book is very tantalizing. His accompanying charts show descent from various counts, dukes and barons of a thousand years ago, to the Viking dynasties and Frankish, Germanic, and Saxon tribes. Also, the charts include your distant ancestors Alfred the Great, Charlemagne, the Carolingians, Merovingians, Byzantine emperors, and then back through Georgian and Armenian rulers of 2,000 years ago to the earliest likely ancestors of King Edward I (1239-1307) of England. It is very likely that all people of English descent would find King Edward I among their ancestors, probably in many places due to extensive intermarriage. This powerful king, sometimes called the “Hammer of the Scots,” has had his princely lineage traced through contemporary records and with the prosopography method back through Byzantine emperors, to kings of Armenia, all the way to King Pharnavaz I, King of Iberia (in what is now eastern Georgia), who ruled from about 299 B.C. to 234 B.C. Wagner’s charts include ancient genealogies of Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Roman emperors of the A.D. 300s, Angles, Saxon, Jutes, the Caesars, Macedonia, the Ptolemies of Egypt, Judaea, and the kings of Syria, Lydia, Babylon, and Persia. It is all rather magnificent!

Anthony Adolph and others have written about the crossover from historical to legendary lineages that go back to Achilles, deep Welsh roots, Brutus of Troy, Hercules, Zeus, pedigrees leading to Old King Cole, and legends that Joseph of Arimathea (possible great-uncle of Jesus) settled in Glastonbury, Somerset, and was a keeper of the Holy Grail. The spread of Christianity in Europe can be traced through the decrees of kings, whereby all their subjects had to fall in line. Norse lines went back to the gods Odin (or Woden, from which Woden’s day or Wednesday came from) and Freya. Once Christianity became dominant, the Dark Ages kings made sure the Norse gods were removed from their pedigrees, and Adam and Eve took their place at the top of the lineages. Mankind has such a desire to ultimately connect himself to the gods and deities, and genealogy has always been a favored way to do so!

Some Key Sources

See part 1 of this blog on the landed gentry for more sources. This is a very limited list.

-

Douglas Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial & Medieval Families (2011 edition: 4 volumes); Royal Ancestry: A Study in Colonial & Medieval Families (2013 edition: 5 volumes); Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families 2011 edition: 3 volumes).

-

Gary Boyd Roberts, The Royal Descents of 900 Immigrants to the American Colonies, Quebec, or the United States (Genealogical Publishing Company, 2018).

- Douglas Richardson, Royal Ancestry, 5 volumes (self-published, 2013); and Magna Carta Ancestry, 4 volumes (2011); and Plantagenet Ancestry, 3 volumes (2011).

- Anthony Camp, Royal Mistresses and Bastards: Fact and Fiction, 1714-1936 (2007).

- William Henry Turton, The Plantagenet Ancestry, Being Tables Showing Over 7,000 of the Ancestors of Elizabeth (Daughter of Edward IV, and wife of Henry VII) (Clearfield, 1993).

- Gary Boyd Roberts, Ancestors of American Presidents, Washington – Obama (NEHGS, 2009)

- Charles Mosley, Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage: 107th Edition (Burke’s Peerage, 2003). This includes knights, Scottish and Irish Chiefs, as well as Feudal Barons of Scotland.

- Burke’s Peerage, Burke’s Family Index (Arco Publishing Company, 1976). Pedigrees from all of Burke’s publications are indexed here.

- John Horace Round & William Page, Family Origins and Other Studies (Genealogy Publishing Company, 1998).

- Anthony Wagner, The Records and Collections of the College of Arms (Burke’s Peerage, 1952).

- Louise Campbell and Francis Steer, et al., A Catalogue of Manuscripts in the College of Arms. Collection, 1 (College of Arms, 1988).

- Paul Chambers, Medieval Genealogy (Sutton Publishing Ltd., 2005).

- “Heralds’ Visitations and the College of Arms,” Some Notes on Medieval English Genealogy (http://www.medievalgenealogy.org.uk/sources/visitations.shtml).

- R. Humphery-Smith, Armigerous Ancestors: a catalogue of sources for the study of the visitations of heralds in the 16th and 17th centuries with referenced lists of names (Canterbury: Family History Books, 1997).

- The Peerage (http://thepeerage.com/).

- Burke’s Peerage (https://www.burkespeerage.com/).

- Bernard Burke, The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales (London: Harrison, 1884); and C. R. Humphery-Smith, General Armory Two, Alfred Morants’ Additions & Correction to Burke’s General Armory (Genealogy Publishing Company, 1973).

- H. Reaney and R. M. Wilson, A Dictionary of English Surnames (Routledge, 1991).

Call Price Genealogy at (801) 531-0920 for a free consultation. Our experienced researchers are ready to assist you with your research into your gentry, noble and royal ancestors, or other ancestral lines worldwide.

Are you a descendant of English gentry? Let us know in a comment below!

Greg