How DNA Testing Has Made Genealogy “Necessary”

5

5Apr

DNA testing has increased the popularity of genealogy in the last few years. The recent media campaigns by AncestryDNA, MyHeritage and 23andMe have increased the public’s awareness of this tool. Its use in law enforcement has also captured headlines. From August 2015 to September 2018, AncestryDNA’s sales have increased by 1000%[1] (from less than million kits to over 10 million!), and 23andMe’s sales have increased by 500% (from less than 1 million to over 5 million). Among family members, colleagues at work, and in other social settings, more and more people want to compare DNA ethnicity results. It is big in social media and is trending so much that people often encourage others to test and discover their ethnic breakdown. People are giving DNA tests for Christmas, and friends are encouraging each other to test by word of mouth.

The Basics

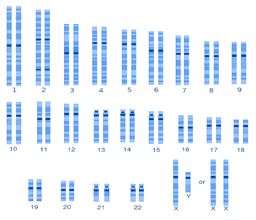

According to Webster’s Dictionary, DNA is “. . . the molecular base of heredity . . .”[2] and therefore forms the basis of who you are, at least physically. You received 50% of your DNA from your father and 50% from your mother. DNA takes different forms, with large amounts of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) powering cellular activity, and with autosomal DNA (atDNA), Y-DNA and X-DNA found in the nucleus of the cell.[3] A consumer can purchase separate mtDNA, Y-DNA and atDNA tests. X-DNA data often comes with atDNA tests, but not every company provides access to the full range of information. These tests can be used to show from which parent, grandparent, or even further back, each segment of your DNA originated. Your DNA matches or cousins share segments of DNA with you.

Understanding Ancestral Lineage Through Y and X Chromosome DNA Testing

In brief, a man’s Y-chromosome passes down from father to son, but not to daughters. Therefore, a Y-DNA tests would only look at paternal lineage. A woman may be interested in her father’s direct surname line, and if so, would want to test her brother or father. A woman has two X-chromosomes, one from her father and one from her mother. The inheritance pattern for women’s X-chromosomes is unique, and the relationship between two people’s matching X-chromosomes can often be determined by knowing this unique pattern of inheritance. Both the Y and X chromosomes help establish one’s ancient ancestral origins.

Men and women inherited their mtDNA from their mother. Women will pass it down to their offspring, but men’s mtDNA is not passed to his children. Therefore, it provides ancestral information strictly on the maternal line, or from one’s mother back through time.[4]

A person’s atDNA comes from both his parents, in the form of 23 pairs of chromosomes in each cell. Of these pairs, one comes from the father and the other from the mother. Autosomal DNA is a particularly useful tool, since these chromosomes are made of segments of DNA from not only your parents, but your grandparents, great-grandparents, and back for several more generations.

The Tests

In a Price Genealogy blog post[5] in January 2019, the five companies providing consumer DNA testing were reviewed. These are FamilyTreeDNA, MyHeritage DNA, 23andMe, LivingDNA and Ancestral DNA. In this post, the focus is on the atDNA or autosomal DNA test. It is the least expensive and offers the most on all your lines, not just the paternal or the maternal lineages. All of the companies offer this test, but LivingDNA has not yet provided their customers with cousin match lists. As of the end of March 2019, AncestryDNA’s client base is over 14 million kits, 23andMe’s is over 5 million, MyHeritage’s is above 2.5 million (and growing rapidly), and FamilyTreeDNA’s is about 1 million.[6]

In late 2015, Ancestral DNA and 23andMe started to mass market their product through various media channels. Television commercials gave their consumers a visual effect of what the test results look like. A print campaign also hit the weekly tabloid magazines and other print media. Each of the companies sold their product for around $100, which was finally affordable for many customers. New books, webinars, and blogs were explaining the concepts and processes of DNA testing in ways that made consumer genetics more understandable to average people, and they in turn promoted testing to their acquaintances. Blaine Bettinger was one of many experts dedicated to explaining the practical benefits of DNA testing. His book, The Family Tree Guide to DNA Testing and Genetic Genealogy immediately became a fundamental source for those who were interested in more than their ethnicity. For those interested in teaching themselves in a workbook format, he, along with Debbie Parker Wayne, published at about the same time, Genetic Genealogy in Practice. These publications thoroughly covered the basics of DNA testing, gave examples of how it can be used for genealogical research, and helped people of all experience levels gain a better understanding of the process.

Even with the emerging availability of guides on interpreting DNA results, the general public often finds it more efficient to consult an expert rather than obtain self-education through publications, classes, and many hours of experience. When DNA for genealogy and ethnicity came into the mainstream, firms like Price Genealogy were prepared to interpret and analyze the results for clients. Such firms would combine their expertise with traditional methods and sources with the newly available DNA test results to solve many types of complex genealogical problems. For their clients who were interested in DNA applications, DNA could now become much more than looking at pie charts or tables of ethnicity percentages.

The Growing Significance of Ancestral DNA in Genealogical Research

For the first time, DNA test results became a big motivation to pursue genealogical research, to find out who were all those matches. Traditionally, genealogists drove DNA sales as they sought another tool to break through ancestral brick walls. Now, casual DNA testers were seeking out genealogists who could make sense of their test results. Hence, DNA is sometimes driving more in-depth genealogical investigations. DNA has made genealogy “necessary” in order to explain their results.

An Example

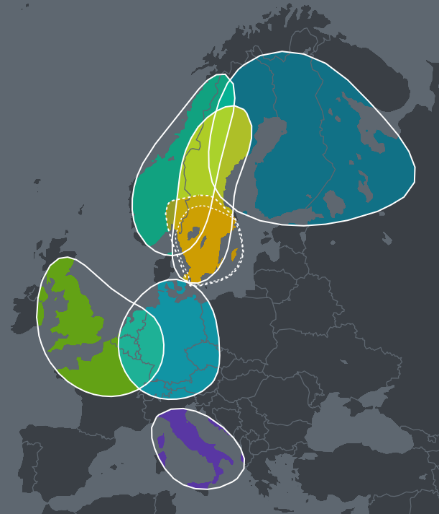

In 2017, my sixteen-year-old daughter took an Ancestral DNA test, following the example of her half-sister who had just done so. Knowing that her father worked in the family history field, she asked me to interpret the results. She wanted to know why I was not showing as a match to her. The answer to that question was simple enough—I had not yet taken a DNA test, which surprised her. Once I took the AncestryDNA test, she and I appeared as a father/daughter relationship match. I looked at her test results and I saw that she had cousin matches with a few of my known relatives. The names of some of the matches were with her mother’s family. The map that displayed her ethnicity estimate was, as expected, comparable to our prior understanding, which does not always occur. Her results overall turned out to be pretty much what would be expected. This was a good start, however, much more could be done to analyze those unknown cousin matches to discover previously unknown genealogical relationships.

In a previous blog post by Price Genealogy, the concept of shared centiMorgan segments (cMs) was discussed.[7] The amount of centiMorgans could be plugged into Blaine’s Relationship Chart which showed averages and ranges of cMs for each relationships or level of cousinship.[8] Therefore, if my daughter had a 339 shared cMs with a person, the chart would indicate that this was indicative of a match with a great-aunt or uncle. There is actually a range of people that could fit for 339 cMs, so it was important to know the age of the other test taker, if possible. We checked these suggested relationships by comparing my daughter’s cMs with several known relationships, and the cMs were consistently correct. Understanding centiMorgans can help you interpret your matches and recognize the variance of potential relationship degrees and types.

Since 2017, this process has become much simpler. Jonny Perl’s DNAPainter was developed in 2017 and then won Rootstech’s DNA Innovaton Contest in February 2018. Subsequently, he took Blaine’s Shared cM Project chart and made it interactive. Perl’s latest online version is called the “Shared cM Project 3.0 tool v4”[9] and it breaks down the percentages of each likely cluster of relationships. He used statistics from Leah Larkin, The DNA Geek.

Conclusion

Genealogy and family history research has become more popular in American culture in recent years. The advent of affordable DNA testing has a lot to do with this. Prices have dropped dramatically, and now for $100 or less, an autosomal DNA test can provide you with an ethnicity estimate and with DNA cousin matches. DNA testing and genealogy now build on each other, drawing energy and insight from each other’s domain. DNA results without genealogy are usually not particularly useful, so genealogy becomes a necessary part of the investigation.

Many people have done these tests but are not quite sure what to do with the great quantity of genealogical and DNA data generated. As with traditional genealogy using paper or digital records, a professional can often discern more from your data than meets the eye. The experts at Price Genealogy can help you solve long-standing problems by analyzing your DNA and the traditional sources.

Mike and Paul

[1] Leah Larkin, The DNA Geek blog, 2018 (www.theDNAgeek.com/dna-tests).

[2] “DNA,” The Merriam-Webster Dictionary (New Edition, 2004).

[3] Blaine T. Bettinger & Debbie Parker Wayne, Genetic Genealogy in Practice (Arlington, Virginia: National Genealogical Society, 2016), 3.

[4] Ibid., 7.

[5] Michael McCormick, “Comparing the Offerings of the Five Big DNA Testing Companies,” Price Genealogy blog, 4 January 2019 (https://www.pricegen.com/comparing-offerings-big-dna-testing-companies/ : accessed 30 March 2019).

[6] Leah Larkin, “Autosomal DNA Test Prices (as of 27 March 2019),” The DNA Geek (https://thednageek.com/dna-tests : accessed 30 March 2019). This also includes database size and processing time information.

[7] Michael McCormick, “DNA Inheritance and The Power of Matching,” Price Genealogy blog, 25 January 2019 (https://www.pricegen.com/dna-inheritance-power-matching/ : accessed 30 March 2019).

[8] Blaine T. Bettinger, “August 2017 Update to the Shared cM Project,” The Genetic Genealogist, 26 August 2017 (https://thegeneticgenealogist.com/2017/08/26/august-2017-update-to-the-shared-cm-project/ : accessed 30 March 2019).

[9] Jonny Perl, “The Shared cM Project 3.0 tool v4,” (interactive version of Blaine Bettinger’s “The Shared cM Project”), last updated 20 April 2018 (https://dnapainter.com/tools/sharedcmv4 : accessed 30 March 2019).