Adding Branches with Church Records

2

2Aug

Church records can give the researcher a wealth of previously unknown information. The names and dates that were captured on a church document may be the key to locating something or someone. A baptismal certificate, a marriage document, or a burial record may include the name of a person listed as a witness, and it may not have been someone that the researcher has ever heard of before. A date listed on one of these items could be useful to pinpoint a relevant date in the life of the subject, which was unclear previously. This “revelation” can be used to locate an aunt, a cousin, or even a parent of the person mentioned on the document. A new branch of the family tree can be added.

The new republic of the United States, where “freedom of religion” was a basic tenet, became a beacon to millions of immigrant settlers who were escaping prosecution in their home country. From the beginning, the Pilgrims, Puritans, and Quakers, came from England to this land to escape the persecution that the Anglican and civil authorities inflicted on them. When they arrived, among the first things that they did was build churches where they could exercise their own beliefs and worship without oppression. In keeping with the custom of their native lands, these congregations kept track of the vital records of their members. The person’s name, date, place, and sometimes parents and witnesses were recorded.

Moving forward a few centuries, immigrant people often lived near each other in ethnic neighborhoods with people who shared their general place of origin, religion and language. This was common in coastal seaport cities, which saw throngs of hopeful immigrants looking for a better life. There was a Chinatown in San Francisco and New York City. Little Italy, Little Germany (Kleindeutschland, or “Dutchtown”), and many Dutch and Irish neighborhoods were also in NYC. The Midwestern states had a huge amount of Scandinavian and Slavic settlers, and their influence is seen in those areas today. Each of these groups established churches in their new-found homes that reflected the faith traditions from their old homelands. In the church books, the priests often recorded the exact town of origin of members of his flock. This vital information is often found on baptismal, marriage and even burial records. This was especially common for Catholic churches, but also occurred with Protestant congregations.

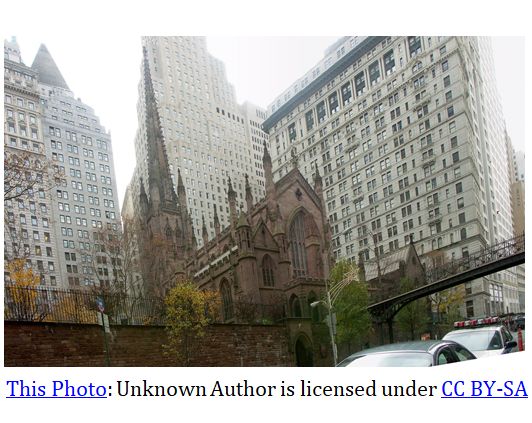

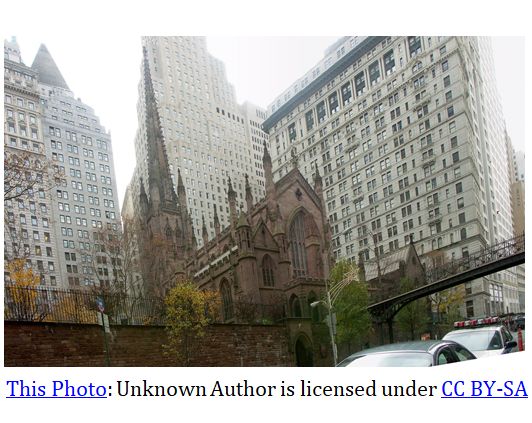

New York City, whose original settlers were Dutch, still has quite a strong presence of Dutch Reformed churches. The English settlers, who started with the Pilgrims and Puritans in New England brought what became the Congregational church to America. The Quakers, Anglicans/Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Methodists did the same. The Lutheran religion came to the United States with the German and Scandinavian settlers, and the Catholic church was common with the Irish, Italian, Slavic, French, and Spanish settlers.

Sometimes church records were kept so meticulously that it is easy to connect one generation to another, as well as siblings and cousins. But, these records can also be quite intimidating, since finding them often requires first learning the religious denomination, and also the exact city neighborhood where the ancestor lived. Fortunately, census records can help pinpoint addresses where these people lived. Finding that address on old maps and locating nearby historic churches and cemeteries can narrow the search for church records. Some cemeteries cater to particular religious groups. One of the authors of this post, Paul, found success with his ancestor’s church records on a recent research trip to his original home in the New York City area.

This excursion focused on finding the baptism record for his father. It started in College Point, Queens, New York where Paul lived as an infant. The location was confirmed by his father’s entry in the 1940 United States census. At this time, the Catholic Church that served this area was St. Fidelis, and a telephone call to the Diocese of Brooklyn’s office confirmed it. A visit to St. Fidelis introduced Paul to Deacon Jack, the parish’s historian. Jack opened the original record book and found an entry referring to the father’s baptism, but the event had occurred elsewhere. Paul’s father was baptized at Flushing Hospital in 1941, when he was five, which was unconventional for Catholics. Deacon Jack went on to explain that the child was probably very sick at the time and was baptized there because he was in jeopardy. The boy did not die. The record of this baptism was found in the Roman Catholic parish of Mary’s Nativity - St. Ann church of Flushing, Queens, New York. A visit to Mary’s Nativity-St. Ann parish led to the baptismal record. On the back of the certificate was the date and place of his confirmation.

Another case study is Paul’s grandmother, who was born in Manhattan, New York in 1909. Her parents were immigrants from France, and they were Catholic. Paul started his research at the Diocese of New York’s website, where it stated: “Each individual parish keeps records of baptism, first communions, confirmations, marriages and funerals.”[1] This is true for many individual churches of various denominations who still hold the only copy of their own registers, often dating back hundreds of years. However, in many instances the records have been copied or moved to a denominational archive. On the New York Diocese’s webpage, there is also a link to a historical list of parishes within the diocese, and where the records are held. The original records would have been moved if the church closed or merged into another. Paul used his knowledge of New York Catholic records to locate an index that mentioned his grandmother’s baptism, and it told him that she was baptized at the St. Vincent de Paul church in 1915, where French immigrants largely comprised its congregation. He used the index to locate the record’s location, and then requested a copy. It listed two witnesses whose names Paul had not previously heard: Francis Chevalier and Marie Chevalier. With a little research, he was able to ascertain that they were her father’s parents.

While the research for this case was done using Catholic record in New York City, this type of research can be successful with the records of most churches. The records of each religion, or even each church, often noted different kinds of information about the baptism, confirmation, marriage or burial. While just sacramental registers have been discussed in their article, there are many other kinds of church records, including membership listings. The records of Catholics, Protestants, Quakers, Jews, and others each require different approaches and methodologies to learn everything that may be available. Even within the same denomination, different communities may record useful information not included elsewhere. For example, immigrant communities may take more care to list places of origin for their members. Information varies even from entry to entry, such as the unusual instance mentioned above of witnesses who were the baptized child’s grandparents. Some of the records are online, but a majority of church records are still only accessible at the parish or at the denominational archive. Like the researcher in these case studies, all our researchers are well versed with using church records to help grow your family tree. Professional genealogists are specifically trained and experienced to glean all valuable information from church records, and Price Genealogy can assist you in your quest for answers.

Paul, KayLynne, and Michael

[1]Archdiocese of New York, https://archny.org (https://archny.org/records : accessed 6 June 2019).