What is Boxing Day?

26

26Dec

Boxing Day, celebrated on December 26th, is a public holiday observed in many countries that were once part of the British Empire, including the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The day traditionally follows Christmas Day and provides an opportunity for people to extend the holiday festivities. It is associated with the practice of giving gifts, often referred to as “Christmas boxes,” to service workers, tradespeople, and the less fortunate. These boxes, filled with money, food, or goods, were tokens of appreciation for services rendered throughout the year, reflecting the Victorian ideals of social responsibility and generosity.

According to the Oxford England Dictionary, the term “Christmas box” dates back to the 17th century. Historically, many servants worked on Christmas Day to ensure their employers’ celebrations ran smoothly, so they were often given Boxing Day off to spend time with their families. This day off was accompanied by the Christmas box, which might include bonuses, leftover food, or practical goods for the  worker’s household. Samuel Pepys, in his diary on 28 December 1668, records being “called up by drums and trumpets; these things and boxes having cost me much money this Christmas already, and will do more.”[1]

worker’s household. Samuel Pepys, in his diary on 28 December 1668, records being “called up by drums and trumpets; these things and boxes having cost me much money this Christmas already, and will do more.”[1]

The term “Boxing Day” also relates to the alms boxes placed in churches during the Advent season. Parishioners would donate money, which was then distributed to the less fortunate on December 26th, often in conjunction with the Feast of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr known for his acts of charity. This tradition of gathering alms for the poor may date back to the late Roman or early Christian ear.

But Boxing Day really became popular during England’s Victorian Era, when the rigid class structure meant that Boxing Day held particular importance in fostering a sense of obligation from the upper and middle classes toward the working class. It was a way to acknowledge the contributions of workers and maintain social harmony. For tradespeople such as milkmen, postmen, and butchers, who often had personal relationships with their customers, Boxing Day was an opportunity to receive tokens of gratitude for their year-round service.

It must be confessed that not everybody felt charitable and selfless about giving to the poor. In the Canterbury Journal from Saturday, December 25th, 1852, the following account was published:

We can hardly close these desultory sketches of Christmas-time without some brief allusion to the day after Christmas, which, through every nook and cranny of the great Babel, is known and recognized as “Boxing-day” – the day consecrated to baksheesh, when nobody, it would almost seem, is too proud to beg, and when everybody who does not beg is expected to pay the almoner. “Tie up the knocker – say you’re sick, you are dead,” is the best advice perhaps that could be given in such cases to any who has a street-door and a knocker upon it. Now is your time to make out a list of occupations, and to become acquainted with all the benefactors who good offices you have been enjoying all the year through without one thought to the gratitude you owe them.

Dab the first is the sweep, or course, who must be paid over again for sweeping your chimneys. Half fearing that if you refuse, you may get a smoky house for the year, you consent for the sake of your lungs, and he is off. You sit down to breakfast, and with the first slice of toast comes dab the second. You glance out of the window, and see a couple of long-coated varlets bearing battered French-horns, and you cheerfully bestow another shilling on the minstrels, as you suppose of the wet and dismal nights. They are off to the next door, and before you have drunk your second cup comes dab the third – the turncock wants his water-rate. You do as you like with him, but if you turn him off empty, he does the same with the water, and leaves you dependent on your neighbors for a supply….[And on and on, from fourth dab up to the ninth.]

…Until at length your patience being exhausted, and your small-change at the same low ebb, you rush desperately into a greatcoat and out of the house…and leaving the dabs to come as slowly as they choose to the unwilling conviction, that “it’s no use knocking at the door any more.”[2]

A scene is set in our minds of a miserly old Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, published in London in 1843. Scrooge is sitting in his counting house with his clerk, Bob Cratchit, when two portly gentlemen come to his door, asking Scrooge to contribute to their collection of alms for the poor. To this Scrooge responds with disgust and a vehement “Bah! Humbug!”

Not everybody felt so miserly, as charity was widely practiced at Christmastime during the Victorian Era. Many of the poor did not beg from door-to-door, but received kindnesses through private organizations or local churches. In the Brighton Guardian in 1865, an article title Wishing the Poor a Merry Christmas “41 aged and deserving poor of the borough were presented by the magistrates from their poor box with a half sovereign each, to ‘keep Christmas.’ More than two-thirds of the recipients were widows. The oldest was 92 and the youngest 66…The recipients appeared very grateful for the seasonable gifts.”[3]

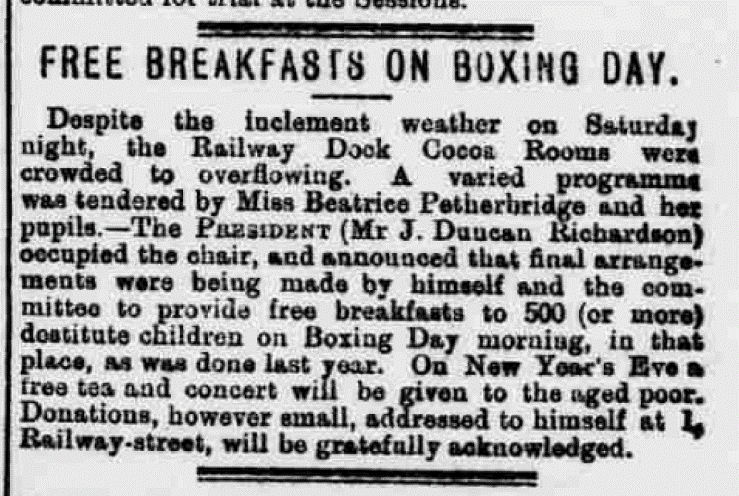

Calls to participate in feeding and clothing the poor can be found all throughout contemporary newspaper articles. For example, in Hull Daily Mail in 1895, an announcement detailed the final arrangements for a free breakfast to 500 or more destitute children being provided on Boxing Day, and asking the public for donations to that cause.

Calls to participate in feeding and clothing the poor can be found all throughout contemporary newspaper articles. For example, in Hull Daily Mail in 1895, an announcement detailed the final arrangements for a free breakfast to 500 or more destitute children being provided on Boxing Day, and asking the public for donations to that cause.

As the Victorian era progressed, Boxing Day also became a day for leisure and recreation. Families might use the day to attend sporting events, take a countryside walk, or visit friends. While the charitable aspects of the holiday were prominent, the combination of giving, rest, and enjoyment made Boxing Day a unique part of the Victorian Christmas season. This blend of traditions laid the foundation for how the holiday continues to be celebrated today. In 1871, Boxing Day was officially recognized as a bank holiday in the UK, cementing its status as a day of rest and celebration.

Modern Boxing Day customs vary by country, but often include shopping, as the day is associated with significant sales and discounts. In countries like the UK and Canada, it is comparable to Black Friday in the United States, with consumers flocking to stores and malls for post-Christmas bargains. Others use the day to volunteer or donate to those in need. Food drives, community outreach programs, and other acts of goodwill are common, reflecting the holiday’s original spirit of giving back to society.

However you decide to celebrate today, we wish you joy, happiness, peace, and comfort. If you would like to learn more about your Victorian ancestors, Price Genealogy can help!

Emily

[1] The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Daily entries from the 17th century London diary, Monday 28 December 1668 (https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1668/12/28/: accessed 26 December 2024).

[2] The British Newspaper Archive, Canterbury Journal, Saturday 25 December 1852, copyright The British Library Board (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001404/18521225/011/0002: accessed 23 December 2024).

[3] The British Newspaper Archives, Brighton Guardian, Wednesday 27 December 1865, copyright The British Library Board (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001641/18651227/125/0005: accessed 26 December 2024).

Images

- Creative Commons, “Alms box in All Saints’ parish church, Moulton, Lincolnshire,” 18 March 2008, Author: Richard Croft (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alms_Box_-_geograph.org.uk_-_734809.jpg: accessed 26 December 2024).

- The British Newspapers Archives, Hull Daily Mail, Monday 23 December 1895 (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000323/18951223/015/0003: accessed 26 December 2024).

- Creative Commons, “Keswick Boxing day hunt 1962,” Keswick Market Square, Cumbria, Lake District, England, Dec 1962, Author: Phillip Capper (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Keswick_Boxing_Day_hunt_1962.jpg: accessed 26 December 2024).