Six Tips for Successful Archival Research

7

7Nov

It’s 2024 and the internet has been changing the entire landscape of genealogy research for over two decades. So many historical records are online—from the big genealogy sites like Ancestry and FamilySearch to volunteer-created databases at local genealogical and historical societies.

Even so, it would be a mistake to assume that everything you need is available digitally. It’s very common that the genealogical brick walls my clients bring to me are solved by tracking down a document that wasn’t available on the internet but instead had to be obtained from an archive or government office.

Archives come in all shapes and sizes. State archives and state- and historical societies might be the biggest institutions, while individual counties and cities often have their own more localized societies and libraries.

You will also find archives that cover specific topics or time periods. Last summer I visited the Drake Well Museum in rural Titusville, Pennsylvania. Their archive is very small and focuses on history of the petroleum industry, as the nation’s first oil well was drilled in northeastern Pennsylvania in 1859.

Philadelphia, where I live, is home to some remarkable religious archives, including the Presbyterian Historical Society and the Catholic Historical Research Center of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Each one of these has genealogically valuable collections that are not (yet) online.

Going for the first time to an archive can be a bit intimidating, but it is so much easier when you understand how things work and put in some prep work! Here are a few tips for getting the most out of an archival research trip.

Number 1: Do your homework ahead of time

Most archives have websites, and those websites usually have catalogs describing what records the archive has. As an employee of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, I regularly direct people to our catalog, which we call Discover (https://discover.hsp.org). We hold over 21 million items in our collection, so there’s a lot to explore for those with Pennsylvania ancestry or who have interest in broader Mid-Atlantic history.

Explore your preferred archive’s site and catalog to learn what makes the archive unique and what they have to offer that you can’t get elsewhere. I recommend searching the catalog by places (“Montgomery County”) and topics (“coal miners”) rather than ancestor names. For further assistance, many archives offer research guides that identify collections they have about popular subjects or for specific audiences, like genealogists. Here’s a great example from the Pennsylvania State Archives.

This homework process will also require an evaluation of where you are in your own research first. What research questions are you trying to answer and what kind of records are you hoping to find that you think could answer it? Be as specific as possible! And make sure your notes, files, and passwords are up-to-date and organized before you walk through the archive’s doors!

Number 2: Review the archive’s rules

Check the facility’s rules so you can arrange your schedule, supplies, and expectations accordingly before you visit. Each one is a little different.

Some allow you to take your own phone pictures of documents, while others don’t. Some have restrictions on how many documents you can look at per day. Many have very limited hours. And most require you to make an appointment ahead of time.

Consider costs as well; archives may be free or—especially in the case of nonprofit organizations—may charge a small fee to visit or for services like scanning.

I don’t know very many archives that are able to afford as much staff as they’d really like to have, which often drives the decisions they make regarding their hours and public offerings, as well as how many of their records they’re able to digitize. Be informed and also patient. Consider donating or becoming a dues-paying member. Many archives also welcome volunteers to help with everything from shelving to transcribing records.

Number 3: Understand how the process works

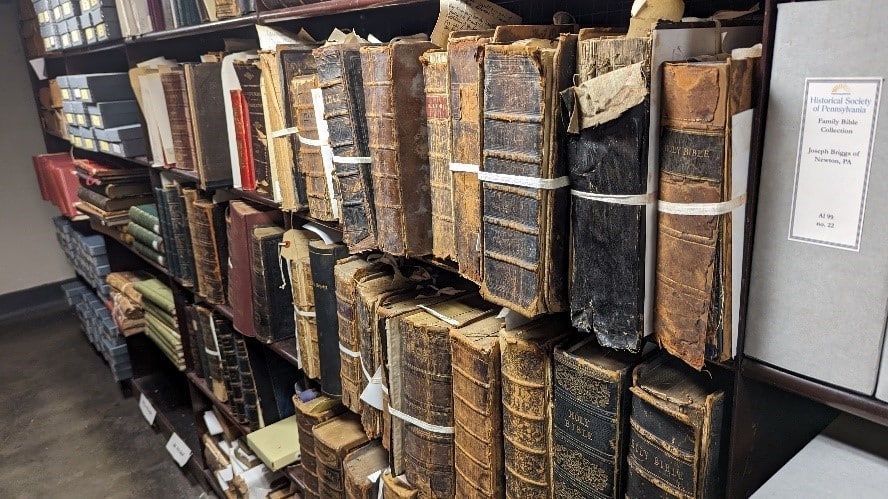

Remember visiting your hometown public library when you were a kid? Visiting an archive is kind of like that, at least in theory. An archive has materials ranging from books to photos to microfilm to boxes full of handwritten papers that they keep on shelves and in drawers. The major difference is that for many archives (unlike your local public library), those shelves are in back rooms and are not accessible to the public. This means that when you visit an archive, you can expect to submit a call slip requesting the item you need (some archives provide paper forms you manually turn in while others have digital systems that allow you to submit your request online while you’re waiting).

In most cases, you’ll be seated at a table in the archive’s Reading Room and a librarian will process your request and bring you the book, box, or file you need. Be aware that this is NOT like searching for a record on Ancestry. Most records are not individually indexed, which means that you’ll likely be spending time looking manually through books and folders for your ancestor.

Here’s an example: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania holds the records of the Children’s Aid Society, which was a foster care society formed in Philadelphia in the 1880s. If you know your ancestor was orphaned in 1895, the librarian could bring you the book of handwritten case histories for children that covers the years 1893 to 1897. For now, there isn’t an index to each individual name for every volume, but we can get you close.

Number 4: Make a plan for your comfort and convenience

Nothing throws off your mood and focus more than an unexpected hiccup in your process. Pre-planning logistics can help! For example, bring a jacket. Most archives are chilly. Figure out how you’re getting there. If the archive doesn’t have parking (as is often the case at urban repositories), be sure you wear comfortable shoes and budget the fees for parking meters or garages into your travel.

If you’re planning to be onsite all day, review what kinds of food storage options the place has. Larger archives are likely to offer patron access to refrigerators and microwaves, saving you the trouble of having to leave for lunch and come back.

Number 5: Ask a librarian (reasonable questions)!

Reference librarians are there to help, so don’t be shy! Any employee sitting at a desk in the public area is fair game to ask questions of, whether about specific collections or logistics. My favorite personal experience was visiting the Library of Congress and asking an employee where the bathroom was. “Over there, behind the Gutenberg Bible” was the response. Not exactly something you hear every day!

But keep your expectations measured and appropriate, too. Remember that librarians are usually not universal subject matter experts, and they can’t know about every topic or every person covered in every record in their library. (Going to a Pennsylvania archive and asking very specific questions of the staff about how to research your Louisiana Civil War ancestor is not likely to yield the answers you need!) Likewise, librarians are not usually trained genealogists, so while they can point you to helpful records, they may not be able to answer in-depth questions about research strategies.

Number 6: Don’t assume you (always) have to go in person yourself

Budgetary or physical limitations can sometimes prevent us from visiting an archive in person, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t access its collections. Archives commonly offer lookup services for a fee and can send you a copy of the record you need. This works best if you have a pretty specific idea of what you need, including the name of the collection or its call number.

You might also consider hiring a local genealogist to visit on your behalf. Paying someone for a couple hours of their labor is likely still cheaper than a plane ticket and hotel night.

That said, there are occasions when going in person is worth your own time and effort if you can swing it. I will often prioritize visiting the place myself where possible if I want to be able to browse through a large collection that I’m not sure has what I need. Time constraints might matter, too. I recently contacted a county archive in Pennsylvania to request a lookup of some estate files, but the staff told me there was a very long waitlist for remote requests. My deadline did not permit me to wait the two or three months they quoted, so I made the drive and was permitted to look at the record I needed that very week.

If you’re still feeling nervous, consider joining group archive tours and trips. This year, the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania hosted in-person tours of both the Pennsylvania State Archives and the Mercer Museum and Library in Doylestown. Do any of your local societies or genealogists offer these services?

Conclusion

One of the principles of the Genealogical Proof Standard is the need to conduct “reasonably exhaustive research.” In order to do this, it’s critical to look for every record that exists that might answer your research question—not just the ones that are easily accessible online.

Archives around the world hold treasures not found anywhere else, and one could contain the document that finally blows your genealogical brick wall wide open. Consider making a visit.

And if you need help along the way with any of your genealogical questions, reach out to Price Genealogy. One our dozens of research experts is sure to be able to help.

By Katy

PHOTO ATTRIBUTIONS:

- Photo of HSP reading room: taken by author.

- Photo of family Bibles at HSP: taken by author.

- Photo of the card catalog from the University Library of Graz: from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schlagwortkatalog.jpg.

SOURCES:

“Ethics and Standards,” Board for the Certification of Genealogists (BCG), https://bcgcertification.org/ethics-and-standards#genealogical-proof-standard-gps