Land Records Part 2

23

23Jul

Previously, we discussed background information about land records, including historical information and what our ancestors had to do to obtain land. We will continue the discussion by exploring what we can find in this paper trail our ancestors’ land ownership left behind.

Previously, we discussed background information about land records, including historical information and what our ancestors had to do to obtain land. We will continue the discussion by exploring what we can find in this paper trail our ancestors’ land ownership left behind.

What land records reveal

Land records are a treasure trove of information, with a history dating back to the early 1600s and spanning many ancestors. Before 1860, ninety percent of white adult males in America owned land. The ownership, acquisition, and disposal of land left a detailed paper trail about our ancestors. Therefore, locating an ancestor’s land can unveil a wealth of information about them.

Land records contain information about the land's buyer (grantee) and seller (grantor). They often mention family members and neighbors. They may also indicate the owner's heirs, including married daughters and their spouses. Sometimes, they indicate where the buyer moved from or where the seller moved to. Whenever land was sold, witnesses had to sign the deed. Sometimes, associates and neighbors witnessed each other’s land transactions.

Some land transactions involved parties of multiple people. Two or more men in a business partnership may have bought or sold land together. If multiple siblings inherited their father’s land, one of the sons sometimes bought out the other heirs. In either case, the index would state the first person's name with et al meaning and others. If a man and his wife were involved in a land transaction, the records may state his name with et ux meaning and wife.

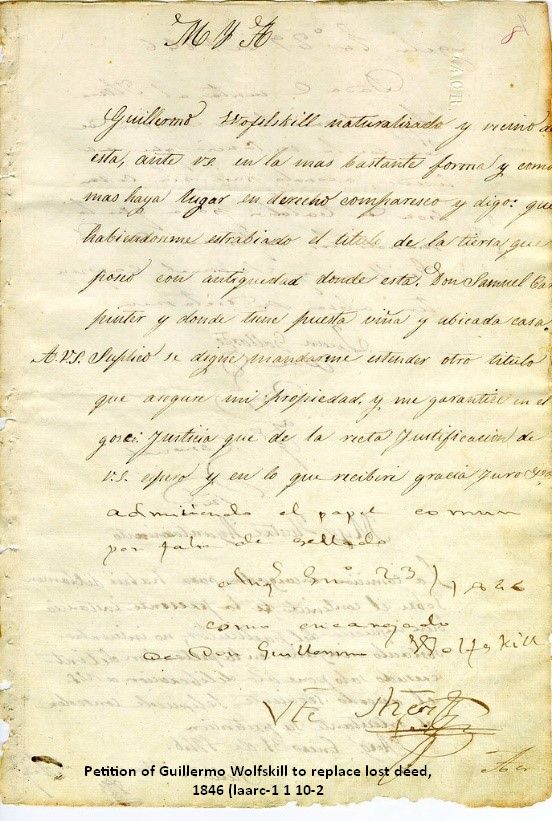

As mentioned previously, a widow was entitled to one-third of her late husband’s property—her dower right. If her husband sold land, she could sue the buyer for her portion back unless she had released her dower right when the land transaction occurred. When a wife released her dower right, her name was recorded on the land record, sometimes her maiden name.

Using land records (case study)

As mentioned, land records often reveal neighbors and relatives, a key aspect in the research of the FAN club (Friends Associates Neighbors). For instance, Consider Hastings bought and sold land throughout the 1790s and 1800s. The same individuals appeared as neighbors and witnesses in his multiple land records. Some of these men were Pages and Pierces/Pearces, the purported maiden names of his wife and mother-in-law. By finding the land records of these Pages and Pierces/Pearces, we can potentially establish relationships to Consider, thereby connecting multiple generations.

Consider Hastings’ deeds were checked for neighbors and witnesses. Had more time been taken with his land records research, the land plats could have been mapped out. This would have given a visual of where Consider and all his neighbors were and the surrounding area.

Comparing land plats with modern (including Google Maps) and historical maps gives a better visual of the lay of the land where your ancestors lived. It can be beneficial to find maps close to your ancestors' time. Topographic maps showing the land's geology, such as mountains and waterways, can increase your understanding of your ancestor’s land.

Comparing land plats with modern (including Google Maps) and historical maps gives a better visual of the lay of the land where your ancestors lived. It can be beneficial to find maps close to your ancestors' time. Topographic maps showing the land's geology, such as mountains and waterways, can increase your understanding of your ancestor’s land.

Platting land in the federal land states means finding the section within the range and township, following a grid. The legal land description gives numbers to indicate the range, township, section, and quarter. The state land states had odd-shaped land plats. The land descriptions can be quite lengthy, describing the perimeter of the land.

To draw out state land state plats, you will want paper and pencil, a protractor, and a ruler. Decide on a scale (such as 1 rod per millimeter), and choose a starting point on the paper. Use the protractor to measure the angles given in the land description and the ruler to measure the length of each side. If you do this with multiple neighbors’ land plats, you can piece them together like a puzzle. There is also land platting software that can do this for you once you enter in the numbers.

It is important to note the room for errors in the metes and bounds survey process. The surveyors would measure the length of the ground, not necessarily the straight-line distance. This would be different in rough or hilly areas. The township-range survey system measured straight lines in six-mile blocks, so states using that survey system don’t encounter those same errors. Additionally, clerks could make errors in copying. These errors are more easily caught and accounted for in hand platting than in the use of software.

Land plats have more uses than only comparing neighbors and community members. They can be used to correlate property records over time. This can help distinguish individuals with the same name or identify heirs when the land was partitioned. Matching up the land can indicate when the land was passed between family members without writing a deed.

Tracing land forward in time can yield more details. In state land states, the language became more precise. Where an older deed said “northerly direction,” a more recent deed of the same land might give a specific angle with degree measurements.

The more deeds you look at, the more complete picture you have of your ancestor’s community. Even looking at the deed index can be helpful because it lists all the residents in a county. There may be ten deeds that solve your genealogical question when you compile the collective evidence, but you may need to go through a hundred to find those ten.

Knowing who your ancestors' neighbors were can help solve genealogical problems. New settlers of an area may have come from the same community back east, or immigrant neighbors may have come from the same homeland. People often lived near extended family. It was common to marry neighbors, as is the apparent case with Consider Hastings. Land records are an excellent way to gauge who the neighbors were.

Land records can be supplemented with gazetteers, county histories, family histories, migration records, and other records. Tax lists will indicate the value of the land and any other taxable property (such as livestock). Census records show where a family lived every ten years and show who the neighbors were. Cemetery records give an ancestor’s death information and may name relatives (heirs). Church records may reveal others with whom your ancestors worshipped.

Finding land records

Now that we know why land records are helpful in your genealogical research let’s discuss how to find them.

If you’re looking for original land patents from federal land states, those can be found on the BLM GLO website. The case files can be found at the National Archives.

If you’re looking for a deed, there are two steps you’ll need to take. The first step is to find the ancestor in the deed index. The courthouses housing the deeds have indexes of all the deeds. The names on the indexes are organized alphabetically, but there are different index systems. Some alphabetize only by the surname's first letter, and some by the first three. Some further divide their indexes chronologically. Determining how the index is organized is key to finding your ancestor or confidently determining he’s not listed.

If you’re looking for a deed, there are two steps you’ll need to take. The first step is to find the ancestor in the deed index. The courthouses housing the deeds have indexes of all the deeds. The names on the indexes are organized alphabetically, but there are different index systems. Some alphabetize only by the surname's first letter, and some by the first three. Some further divide their indexes chronologically. Determining how the index is organized is key to finding your ancestor or confidently determining he’s not listed.

When you find your ancestor in the index, there will be a corresponding deed book and page number for your ancestor. The second step is to find that book and turn to that page number. If you do this process in person, you will handle big deed books at the courthouse. Fortunately, many deed books have been digitized by FamilySearch. Many of them are unindexed, so they need to be browsed. It is easy to jump around the images in a digitized FamilySearch collection. You can type a number into the image number box in the top-right corner or scroll out until the images are all thumbnails and select a different one. It is recommended to make big jumps until you get to the letter section for the surname you’re searching for, then make smaller jumps. In some indexes, it may be necessary to find the beginning of a given letter section and browse its entirety. The same jumping trick can be used to find the deed within the deed book, but you’ll check the page number instead of the index section.

To find a land record collection in FamilySearch, either search in the Card Catalog or the Research Wiki. In the card catalog, enter the ancestor’s town or county into the Places box and “land records” into the Subject box. In the research wiki, navigate to the state or county in question and select Land Records from the list in the box.

If no deed was recorded for your ancestor’s land transaction, you may find it in a published book of unrecorded deeds. Such books and manuscripts can be found in historical societies.

The Library of Congress has land ownership maps, which can be found in the FamilySearch card catalog. Additionally, plats can be found in plat books, probate papers, and surveys. Additional resources can be found by doing a Google Search for “land records” + state.

Can land records help solve your genealogical problems? Price Genealogy would be happy to help.

By Katie

Resources

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/metes-bounds-land-plats-solve-genealogical-problems/?search=land

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/comparing-plats-of-land-with-deeds-and-grants/

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/land-records-solve-research-problems/

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/u-s-land-records-state-land-states/

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/lineage-of-land-tracing-property-without-recorded-deeds/?search=land

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/neighborhood-reconstruction-effective-use-of-land-records/?category=records&subcategory=land&sortby=newest

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/squatters-pre-emptioners-and-thieves-early-land-records/?category=records&subcategory=land&sortby=newest

- Daniel Shaw grantor, Consider Hastings grantee, 8 June 1803, “Volume 17,” 570; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465511, image #578.

- Varney Pearce grantor, Consider Hastings grantee, 8 June 1803, “Volume 18,” 306-307; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465512, image #168.

- Varney Pearce grantor, Consider Hastings grantee, 8 June 1803, “Volume 17,” 572; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465511, image #580.

- William Walter grantor, Consider Hastings and Joseph Putnam grantees, 8 June 1803, “Volume 18,” 307-308; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465512, image #168-169.

- Jacob Smith grantor, Consider Hastings and Joseph Houlton grantees, 16 July 1798, “Volume 11,” 516-517; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465506, image #530-531.

- Daniel Shaw grantor, Consider Hastings grantee, 8 June 1803, “Volume 17,” 573; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465511, image #581.

- James Shaw grantor, Consider Hastings grantee, 12 September 1805, “Volume 22,” 197; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465514 , image #459.

- Consider Hastings grantor, Warren Peirce grantee, 18 July 1807, “Volume 25,” 16; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465516, image #15.

- Consider Hastings grantor, Samuel Rice grantee, 14 February 1809, “Volume 25,” 658; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465516, image #346.

- Consider Hastings grantor, James Freeman grantee, 18 October 1809, “Volume 26,” 401-402; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465517, image #220.

- Consider Hastings grantor, Hannah Pearce grantee, 14 October 1809, “Volume 26,” 411; Franklin County, Massachusetts Franklin County Court House Registry of Deeds Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org, Film #007465517, image #225.

Photos from D Rogers