Using Deeds in Hawaiian Research

16

16Feb

Tracing Hawaiian ancestors poses a unique challenge for researchers. Among them are an almost non-existent written language before the 1820s, unique naming practices, and a lack of consistent record keeping. One of the richest records in Hawaiian genealogy are deeds.

The Great Māhele

Prior to 1848, Hawaiian commoners were not allowed to own land. Instead, all of the lands in the Hawaiian Islands were owned by the monarchy. The 1840 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii laid the foundation for private land ownership in Hawaii. The Māhele took effect in 1848, and the crown divided the land into three parts:

- 1/3 Crown lands, which was to be reserved for the monarchy and their family.

- 1/3 Government lands, which could be sold by the monarchy for profit.

- 1/3 Konohiki land, which was reserved for the Hawaiian people.

The Kuleana Act of 1850 gave Hawaiian commoners two years to petition the crown to obtain title for the land that they farmed and lived on. This was the birth of private land ownership in Hawaii.

Hawaiian Deeds

How can deeds help with Hawaiian genealogy research? With Hawaiians now able to privately own land, they had the opportunity to buy and sell their properties. This means that they would often sell to family members and close friends. Many Hawaiian deeds note if there is a familial relationship between buyer and seller, and the seller will often note where he got his land from. If he inherited the land from a family member, it was noted on the deed. Many times, descendants of Kuleana Act land recipients inherited land from their deceased family members. This relationship between the Kuleana land recipient and the descendant is almost always noted.

Even adoptions can be recorded in deeds.

Because of a lack of consistent vital records in Hawaii, sometimes the only way you can prove a relationship between two people is through deeds.

Finding the Records

We are lucky to live in a digital age, and thanks to FamilySearch we can access Hawaiian deed books from 1844 to 1900 online for free. If you are looking for copies of deeds after 1900, you will have to obtain them from the Bureau of Conveyances.

The deed books can be found through the FamilySearch catalog. Once you register for a free account, you will be able to access the digital images. You can access the collection through Search>Catalog>type in “United States, Hawaii” and hit search>click the heading “Land and property”>Deeds and other records (Hawaii), 1844-1900; index, 1845-1917.

There are two search boxes – one for the Registrar of Bureau of Conveyances, and one for the Grantor and Grantee Index. It is important to note that only a portion of the deed books are indexed – however, the index books are completely searchable by clicking on the “Grantor and Grantee Index” search box. This is the database that you are going to want to search first.

Researching

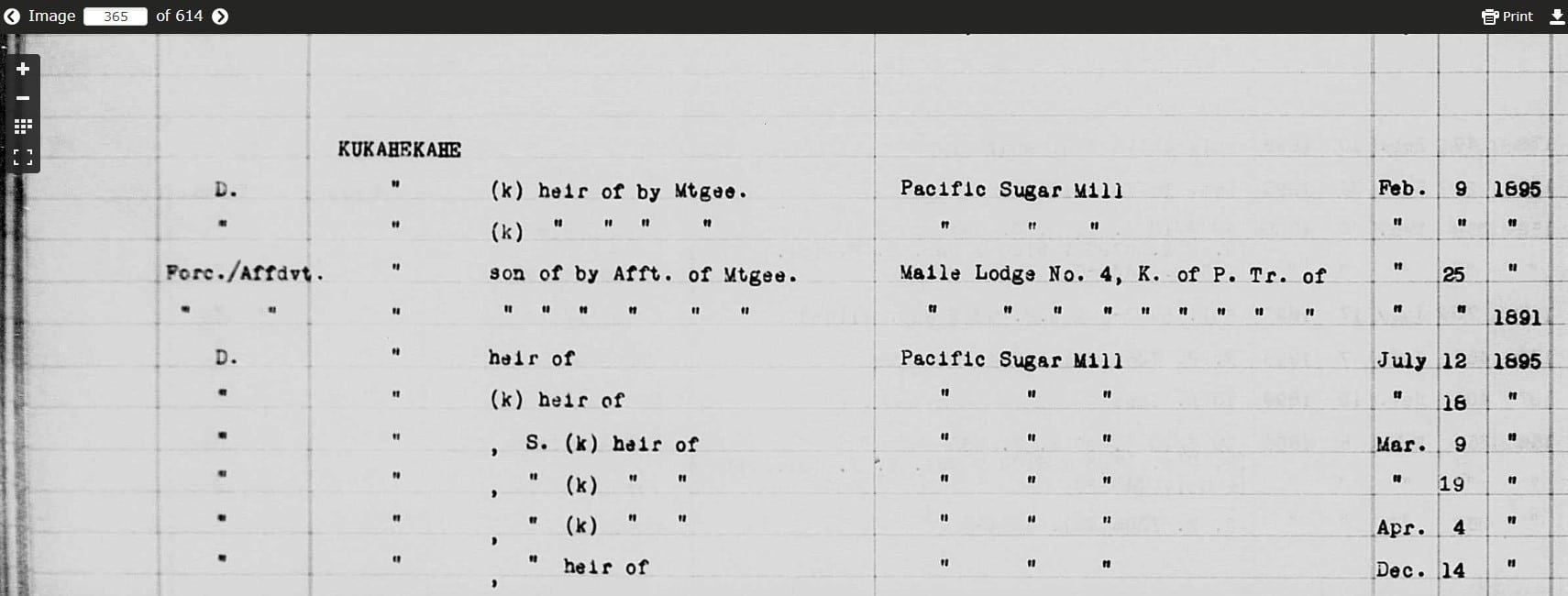

After you perform a search for your ancestor and you find a record of interest, open the index image to reveal additional information. This information will be vital in getting to the deed record. Make note of where your ancestor lived, specifically starting with the island that your ancestor lived on.

The index book will provide information such as the type of record, grantee/grantor, date of transaction and date of recording, the book and page where the deed can be found, and the description of the land.

Once you find the record you are interested in, make note of the deed book and page number. Now you will go back to the database homepage and scroll down to the book number that your record is in. Note that each image set contains multiple books. Clicking on the camera icon on the record set that contains your deed book will bring you to the images. Use the + and – buttons to quickly navigate to the correct book and page. Once you get there, you will have your deed! Now the fun begins.

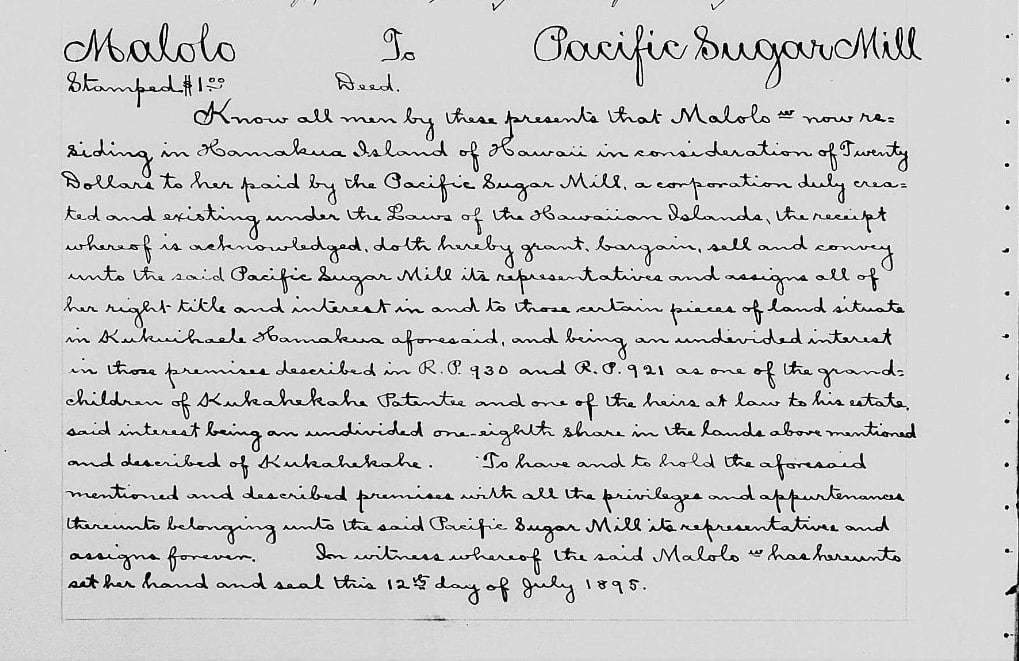

Read the deed carefully, and make note of names, relationships, Royal Patent (R.P.) numbers, and Land Commission Award (LCA) numbers.

1. Example of the Index Book

Case Study

Kamalolo “Malolo” Holoholokulani was a Hawaiian woman born in 1871. When trying to find her parents, traditional records like census, marriage, and death records came up empty handed – the only clue to her family members being the witnesses on her marriage record.

A search for Malolo in the deed books produced a deed between Malolo to Pacific Sugar Mill in 1895. The deed records that Malolo sold “her right, title, and interest in and to those certain pieces of land situate in Kukuihaele, Hamakua, aforesaid, and being an undivided interest in those premises described in R.P. 930 and R.P. 921, as one of the grandchildren of Kukahekhae, patentee.”

The deed itself was not enough to discover Malolo’s parents. More deed research was needed. An 1893 lease between S. Kapela, Holoholokulani, Kawelo, Malolo, and Poka provided additional information. Written in Hawaiian, the lease states that they are leasing their interest in R.P. 930 and R.P. 921 as heirs of Kukahekahe. Are they siblings and grandchildren of Kukahekahe? The clues in the deed records stopped here. This is where we need to turn to other records.

Researching all of the other names on the lease discovered a probate record for Kawelo. Kawelo’s widow listed that her husband’s siblings were Kaluai, Lydia, Kapela, Holoholokulani, Malia, Malolo, Kupuohi, Kaanoi, and Ana. Now we have confirmed that these are siblings and grandchildren of Kukahekahe.

In researching the siblings further, an obituary for Kaanoi was located. It named her parents as Rev. Pupulenui and Hookiekie. Since we know these children are siblings, then Pupulenui and Hookiekie should be the parents of Malolo. An 1853 marriage between Kapupulenui and Kahookiekie gives evidence that all of these children are full siblings, and are all the children of Pupulenui and Hookiekie.

Moral of the story: without locating the deed records and finding the sibling’s names, we would not have come across Kawelo’s probate record or Kaanoi’s obituary, which confirmed that Malolo is the daughter of Pupulenui and Hookiekie.

2. Deed between Malolo to Pacific Sugar Mill

2. Deed between Malolo to Pacific Sugar Mill

Search Tips

- Locate all deeds for your ancestor and transcribe them.

- Search for siblings by looking for “heir of” in the index.

- Although most deeds were recorded shortly after the transaction took place, do not discount records that are dated years after you expected your ancestor to have purchased/sold land.

- Make note of the Royal Patent (RP) and Land Commission Award (LCA) numbers and locate the Kuleana land petition.

- Search for your ancestor’s name in various ways. For example, some people dropped the “ka” or “ke” from the beginning of their name (example, Kapupulenui was known as Pupulenui).

- Search your ancestor’s name in just the first name field on the search page and use an underscore in the last name field (it will not let you search without something in the last name field). Depending on how the record was indexed, people with only one name may be indexed in either the first name field or the last name field.

- Use other records such as vital records, newspapers, and probate records to confirm or find additional information for relationships.

Understanding the Deeds

It is important to note that some of the deeds are written in Hawaiian while others may be written in English. Most deeds that involve corporations will be written in English, while deeds between Hawaiians are written in ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi – but not always. Using a Hawaiian dictionary or a translation service can help you if you cannot read the language.

Some examples of the types of deeds you will find are:

- Land sales

- Leases

- Adoptions

- Mortgages

Next Steps

Continue doing research to locate where the land is on a map, and to further confirm relationships that are listed on the deeds. One important thing to note about Hawaiian relationships is that sometimes “makua kāne” could be a father, uncle, or male cousin on the father’s side.

Have fun climbing your family tree!

Resources

- Grantor and Grantee Index Search - https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/2821304

- Bureau of Conveyances - https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/boc/general-public/

- Hawaiian Dictionary - https://wehewehe.org/

- Hawaiian Translation Service - https://awaiaulu.org/

- YouTube Video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X8tUtAZoLk8&t=1025s

- YouTube Video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DGMLgftzJUw

Photo

Aerial view of Hawaii https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hawaje-NoRedLine.jpg / Jacques Descloitres, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons