Discovering Your Family’s History Through Genealogy

6

6Oct

Genealogy is research into your family, about your family. It uncovers stories and shows where your ancestors were in history. What were they doing during a revolutionary or civil war? When did they come to or leave their hometown? How many generations lived and died on a single farm? Did they work in trained occupations like smithing, tailoring, or shoemaking? Were they more mobile as a sailor or a soldier? Which ancestors were widowed and did they remarry?

Parents tell children stories, passing down memories of grandparents. Churches record attendees and participants in religious events. Governments enumerate taxpayers, list soldiers, and certify vital life events. Historians write about families, important figures, and significant events. Books describe families who settled towns and colonies—who they married, what their occupations were, their political or military activity, their residences, and their children. Records show when a bachelor cobbler married a widow seamstress or when a factory worker’s daughter was born at home. Newspapers publicize the mining accident that killed dozens, a divorcing couple, obituaries, etc. [1]

To protect the privacy of the living, few government records created after the early- to mid-1900s are available freely online. Genealogy research for several decades prior to now relies on living memory, public records, and DNA testing. What stories can your parents and grandparents tell about their parents and grandparents? What about your cousins and DNA matches? Social media and newspapers might tell you what people cannot.

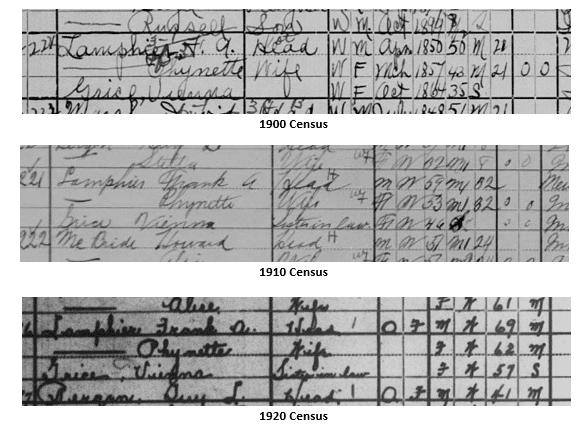

Census records often describe households—surnames, what work the head did, how many people lived there, where the family lived. Each government had different priorities and changed what information was recorded frequently. The United States started taking a federal census every ten years in 1790; the 1950 census is the most recent census online. Beginning in 1850, the census named all individuals in a house, not just the head. Each census contains useful information about age and gender, while the later ones also include occupations, birthplaces, and relationships. England, Wales, and Canada also have ten-year censuses but in years that end with “1” instead of “0.” Canada censuses sometimes detailed a person’s religion. England and Wales specified an individual’s birthplace down to the county or parish, although they sometimes rounded an adult’s age to the nearest five.

A Story of Close Siblings

Henry and Elizabeth Grice had several children, including two daughters named Phynette and Vienna. Phynette, born in 1857, was six years older than Vienna. The sisters grew and Phynette married Frank Lamphier in 1878. Vienna did not marry. Phynette and her husband never had children. Vienna lived with them for decades; they were recorded together for the 1900, 1910, and 1920 censuses. [2]

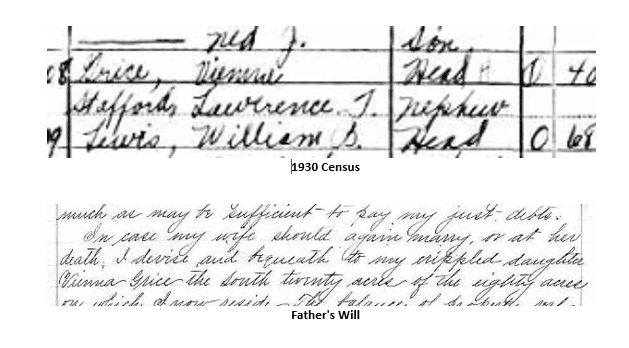

A single woman such as Vienna could have lived alone in that time period, so why did she live with her sister? Then Phynette and her husband died. For one census, Vienna would have been alone. But Vienna had more family. When the 1930 census was taken, another sister’s son was living with her. [3] Vienna died a few years later. When her father Henry died in the 1880s, he left a will that described his “crippled daughter Vienna.” [4] Vienna may have been physically or mentally disabled in a way that she could not live alone. Genealogy research found a family that remained close and cared for each other.

When someone died with property, probate records started. Sometimes someone would leave a will in which they would name their surviving heirs and describe their inheritance. A parent would usually mention a daughter’s married name, like Phynette Lamphier. A will might hint at family stability or drama. For example, a father might mention that he was not leaving anything to a child other than property already given him. That was especially common with farmers with a son who remained in the home after starting his own family. If a dying man were leaving a widow, he would name her and often describe her as “my loving wife.” But sometimes a will might detail a more turbulent relationship.

A Story of an Angry Spouse

One man in colonial America left his “unnatural Cruel Tyrannical and Barbarous Wife Jannet” an old bed, two blankets “and no more because she has refused to cohabit with [him] for the space of four years and hath refused to take care of [him] in [his] sicknesses.” Robert’s will shows that he was ill for several years; he and his wife were not close. Where did his wife live? Did his children care for him? Was theirs a relationship covered in local newspapers? Their family’s story included relationships as difficult as modern ones.

Records of property passing from one generation to another started early but not everyone left a will or was described in one. In colonial America, record keeping was done by local towns and churches who were not standardized by a larger organization. Town records were often similar to a community diary; they described births, marriages, and deaths in addition to local elections, political activity, property disputes, etc. While they were often written chronologically, an entire nuclear family might be described on one page. Church records often overlapped with public records, such as marriage, but focused more on religious events and activity. Baptisms were often the primary objective and could be of children or adults depending on the faith. Burials often happened in the church-maintained graveyard. People of the colonial period did not often separate church and government, so an area’s records might be in one group labelled as church or town records. These records have often been used as the basis of published genealogies and histories. Books like these are very helpful in finding and identifying families as someone has already sorted through the original record to find the important stories.

A Story of a Determined Couple

George Layfield was a significant figure in Somerset, Maryland in the late 1600s. He was a customs officer, revenue collector, a deputy notary, “first vestry of Coventry Parish,” and “no doubt a man of substantial means.” He first married the widow of another important man but it was his second marriage that made many court records. Church of England beliefs about marriage became local law.

“In 1697 Colonel Layfield, who, about 1695, had become a widower, and was now at least nearing fifty years of age, became enamoured of the Somerset beauty and heiress, Priscilla White, who was less than half his age. What constituted the supposed horrible unlawfulness of a marriage between Layfield and Priscilla White was the fact that the young lady was a niece of Layfield’s deceased wife.”[5]

Local society was in an uproar. The couple had to be married according to another religion’s practices. Witnesses to their marriage were “summoned before the Governor” to answer for their participation. A published genealogy details the drama that stretched from 1697 to 1700. George and Priscilla’s marriage was finally recognized and they had one daughter before George died in 1703. Priscilla later remarried and had more children.

Genealogy finds your ancestors’ stories. They were people like we are today. You may find generations of farmers, pioneers, sudden deaths, poverty, wealth, unexpected relationships, political work, religious activity, and more. Research your ancestry to find your family’s history.

At Price Genealogy we have a team of expert researchers who can help you find the often fascinating stories that will bring your ancestors to life.

By Chloe

[1] Image from Newspapers.com

[2] Image from FamilySearch copy of census.

[3] Image from Ancestry copy of census.

[4] "Indiana, Wills and Probate Records, 1798-1999," database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed 11 September 2023), entry for Henry Grice, 1877, Clinton County, Indiana; citing "Clinton County Probate Records, 1831-1921; Author: Indiana. Circuit Court (Clinton County); Probate Place: Clinton, Indiana.”

[5] Torrence, Clayton. Old Somerset on the eastern shore of Maryland; a study in foundations and founders, pages 375-179. Internet Archive. Baltimore Regional Publishing Company, 1966.