Bounty Land

23

23Jun

Land was important to many of our ancestors. The government recognized this and used it as a reward for military service in the early days of our nation. Like other land granting, this left a paper trail of value to genealogists. Continue reading this article to learn about this genealogical asset.

Bounty land process & History

The earliest known bounty land dates to ancient Rome. Caesar recognized the value of giving land to soldiers. This permanent reward did not require the state to use cash. He used such land to place retired soldiers in newly conquered areas in what is now Spain, France, England, and northern Italy. Two additional benefits of rewarding soldiers with land were that it relieved overpopulation and placed trained soldiers in the borderlands. These soldiers had a natural incentive to defend the land they had previously conquered.

The English Crown used bounty land in medieval and early modern times. This included land in the borders of Wales, Scotland, and Ireland in the 1200s and Cromwellian and Ulster settlements in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

In the English American colonies, Land was granted to soldiers in almost every colonial New England battle. A soldier who enlisted for a short time still received land. Furthermore, frontier settlements were required to have a stockade and militia. Some areas in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York designated settlements as military towns. Military men would receive land there but were not allowed to leave without prior permission, or they would lose their land grants.

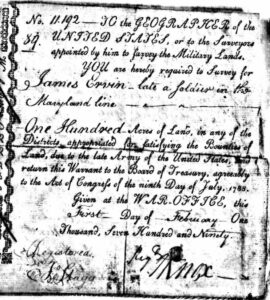

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress promised land in exchange for service. Of course, they would only have land to give if they won the war. In what is now Ohio, land surveys were begun for the military tract of land in 1776. This was the same year that the first federal bounty land became available.

Bounty land was scaled by rank, with greater tracts of land being offered to higher-ranking officers in the war. This land incentivized soldiers to serve and provided a pension to pay for service. Like in the olden days, giving bounty land on the frontier was a way to encourage veterans to migrate westward and provide a defense. In cases where the bounty land warrant was sold to land speculators, this also brought others westward to the frontier. Often, a veteran or his widow would sell the warrant if they could not move to reside on the land. Most warrants were sold.

The federal government and individual states granted bounty land. The federal government mainly granted land in Ohio. States that granted bounty land included Georgia, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, North and South Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Massachusetts gave land in Maine. North Carolina gave land in Tennessee. Virginia gave land in Ohio and Kentucky. Due to multiple states trying to issue bounty land in the same areas, they had to cede land to the federal government. Then the federal government could give that land to soldiers. Some colonies did not have enough land to provide bounty land, including Delaware, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Each state had its own rules and systems. British deserters qualified for land in Georgia. Pennsylvania’s land grants were donation land rather than bounty land.

To apply for bounty land, a veteran had to submit affidavits from commanding officers or fellow soldiers, along with discharge papers. If a soldier died in service, his heirs could apply for bounty land by proving they were his legal heirs. Once the bounty land was approved, the warrant was issued. The next step was the survey. Finally, a patent would be given to the warrantee. The patent meant ownership of the land.

At first, the secretary of war processed bounty land warrants, and the treasury department was in charge of land in the public domain. The General Land Office (GLO) was established in 1812, creating an administration method. Land was distributed in quarter sections of townships; This was the beginning of the state land state survey system.

Until 1830, federal land warrants could only be used to claim federal military district land in Ohio. An act of 1830 allowed for unused warrants to be exchanged for land elsewhere.

Acts in 1850, 1852, and 1855 granted bounty land to veterans of wars since the Revolution, including the War of 1812, the Indian wars, and the war with Mexico. Widows and minor children were entitled to land in proportion to certain service periods. Land was granted from any land office of the U.S. Most acts allowed immediate heirs to obtain warrants.

Contents

What can be found in records of bounty land? The application lists the soldier’s name and age, residence at the time of application, and service details. The application will include a soldier deposition and affidavits of witnesses, usually fellow soldiers.

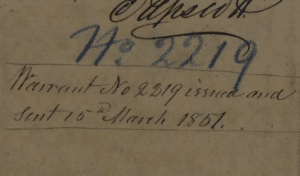

The bounty land warrant includes the number of acres and the bounty land act the soldier qualified under. The surveys sometimes list neighbors. Sometimes the bounty land numbers include the number of acres and the relevant act. The bounty land warrant number for Anthony W McKinney is 2219-160-1850. This means he was granted 160 acres of land under the Act of 1850. 2219 is his warrant number.

Anthony W McKinney served in the War of 1812 in the U.S. Rangers under Captain Samuel McCormick. He applied for both pension and bounty land, so those are filed together for him and his widow, Catharine.

Anthony W McKinney applied for bounty land in 1856 under the Act of 1850. His warrant was issued on 15 March 1857. His bounty land application indicated he was fifty-four. However, this aligns differently from other reports of his age within his pension file, and that age would have had him serve in the War of 1812 at age ten.

His bounty land and pension applications indicated his service in the U.S. Rangers. He enlisted in Dayton, Ohio, on 25 October 1813 and was discharged on 27 October 1814. He served as a private in Captain Samuel McCormick’s company. This information was listed in several papers within the file, including his original discharge papers.

After Anthony died, his widow, Catharine, applied for a widow’s pension and bounty land. In 1881, she filled out almost identical forms for both. (The clerk forgot to write out the decade, so the forms mistakenly said 1801.) Not only did she have to provide information about her husband’s service, but she also had to prove her marriage to him and his death.

According to Catharine’s application, Anthony enlisted at the beginning of the war and served until the end. She gave a physical description of him at the time of his enlistment: brown eyes, black hair, light complexion, age eighteen, farmer, born in Kentucky, six feet tall.

On her application, she reported that they were married on 8 April 1850 in Fairview, Randolph, Indiana, by Reverend Muller. Her maiden name was Catharine Morical. She and Anthony had resided at Fairview until his death on 20 August 1873. She also mentioned that he had been previously married to Elizabeth Bracken, who died about thirty years prior in Fairview, Indiana.

Searching for bounty land

Before searching for bounty land, you should determine if  your ancestor had any. In the case of the McKinneys, this was easily determined by obtaining their pension file because it was filed there. This will not always be the case. Ancestors who did not qualify for pension may have still qualified for bounty land. If your ancestor lived in New England, check the town history. Most of these tell how the land was acquired and who the first settlers were, which could give clues to the existence of bounty land. Also, familiarize yourself with the history of your ancestor’s area. If they migrated to a place where bounty land was given, investigate that possibility. One example of this is an ancestor who migrated from East New York to West New York; the county they migrated to was one where New York was offering bounty land.

your ancestor had any. In the case of the McKinneys, this was easily determined by obtaining their pension file because it was filed there. This will not always be the case. Ancestors who did not qualify for pension may have still qualified for bounty land. If your ancestor lived in New England, check the town history. Most of these tell how the land was acquired and who the first settlers were, which could give clues to the existence of bounty land. Also, familiarize yourself with the history of your ancestor’s area. If they migrated to a place where bounty land was given, investigate that possibility. One example of this is an ancestor who migrated from East New York to West New York; the county they migrated to was one where New York was offering bounty land.

Anthony and Catharine McKinney’s bounty land and pension records were filed together and found on Fold3 in the pension collections. Had they not been filed together; the bounty land collections would have had to be searched.

Fold3’s bounty land collection is only indexed to L. Anyone after that, such as McKinney, would have to be ordered from NARA using their form if it is not part of a pension file.

Other places to search for bounty land records include Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, and the National Archives (National Archives and Records Administration). Indexes are a good starting place to search because they point to original documents. Such indexes and records are available both online and in published books. An excellent article with links to Bounty Land Warrants can be found in the FamilySearch.org Wiki.

Ancestry.com has databases for bounty land applications, warrants, and a state grand index. Their warrant collection did not include warrants for those who received bounty land under acts of 1850 or later, so the McKinney’s bounty land warrant was not housed there. When searching the Ancestry databases, do not limit it to just the name. Sometimes searching the warrant number pulls up results where the name is blank; these results are missed in a name search. Such was the case when searching Anthony W McKinney’s warrant number. (Unfortunately, those blank entries were not his.)

The FamilySearch Wiki lists resources for searching bounty land records in the following states:

- Federal Bounty Land Warrants

- Georgia

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- New York

- North Carolina

- Pennsylvania

- Virginia

- Maine

- Tennessee

- Ohio

Other FamilySearch collections can be found in the Card Catalog by searching “bounty land.” Additional resources are available in Ancestry’s Red Book Online, Military Bounty Land by Christine Rose, and Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants: Awarded by State Governments by Lloyd Dewitt Bockstruck.

If you cannot find the bounty land record online or it is not indexed, check NARA. Many records at NARA are not digitized, so you would have to go to the National Archives in person or order a record using their order form. Some records may be off-shelf because NARA is preparing to digitize them.

Bounty land applications are within the collection for Records of the Veterans Administration. NARA (National Archives and Records Administration) also has custody of bounty land warrants used to obtain land. These are arranged by act of Congress. Some of these warrants have name indexes. Searching “bounty land” within the NARA catalog pulls up many collections. Another collection in NARA includes reproductions of early warrants lost in fires in the War Department.

If you want to locate the land your ancestor was awarded, you can search for them on the Bureau of Land Management General Land Office website. Most of the federal bounty land was granted in Ohio, so this would be under the Military Survey meridian. Search all patentees and patentors in your query.

If you need additional help searching for your ancestor’s bounty land, Price Genealogy can help.

Katie

Resources

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/2-finding-your-ancestor-in-pension-and-bounty-land-files

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/go-west-american-migration-1783-to-1900

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/american-revolution-genealogy/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar&sortby=newest

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/2-finding-your-ancestor-in-pension-and-bounty-land-files

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/the-war-of-1812-records-preserving-the-pensions/

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/u-s-revolutionary-war-a-case-study-approach/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar

- https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_usa_2_d/5/

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/revolutionary-war-series-5-of-5-records-created-by-the-revolutionary-war- after-the-war-bounty-land/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar&sortby=newest

Photos used by permission of Diane Rogers