Are You Descended from English Gentry, Nobility or Royalty?

2

2Jun

American genealogists have long sought for “gateway ancestors,” many of whom lived in the colonial period, who might give them a pathway to royalty and to earlier historical times. It can be very satisfying to find that you are genealogically connected to the high tide of history. This blog intends to help you find a generational path from the English landed gentry back to titled nobility, and hopefully, to royalty.

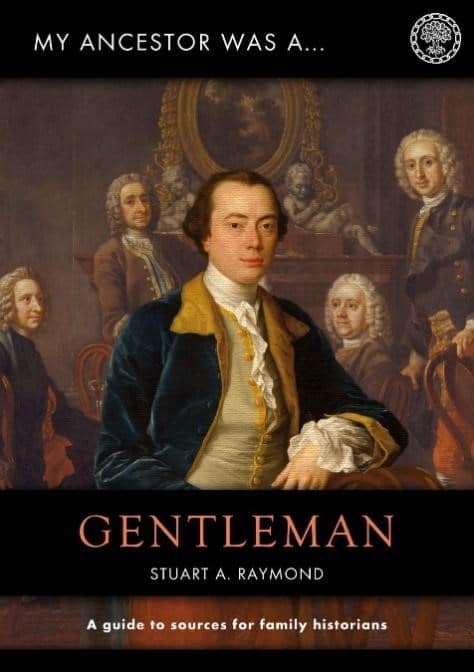

This topic is dealt with very thoroughly in Stuart A. Raymond’s excellent book, My Ancestor Was a Gentleman. It is highly recommended reading if you suspect that your ancestors may have been members of the landed gentry or if you see “gent.” affixed after their names in documents.

This topic is dealt with very thoroughly in Stuart A. Raymond’s excellent book, My Ancestor Was a Gentleman. It is highly recommended reading if you suspect that your ancestors may have been members of the landed gentry or if you see “gent.” affixed after their names in documents.

People sometimes look at huge books like Burke’s Peerage and Burke’s Landed Gentry, with their tens of thousands of names, and figure that these were not “their people” and that there is no way they could descend from nobility or royalty. Yet, those tens of thousands of people have hundreds of thousands of relatives, cousins, and descendants. The younger sons of royalty were noblemen, and their younger sons might have been influential gentry or baronets, knights and esquires. From there, younger sons often formed the lessor gentry and would simply be referred to as “gentleman.” Their younger sons were “yeoman,” whose younger sons may have been “husbandmen.” It is not hard to imagine that the next generation down could have been landless laborers. In a system of primogeniture, where the eldest son inherited all the real property, this was a common pattern.

As you examine your ancestral lines from the opposite direction, pay attention to those lines which seem to rise a little with each generation back, or for whom it appears that a man of lesser status had a fortuitous marriage to a woman who herself may have been a younger daughter of a family of ever-increasing importance.

There is an allure of endless genealogies through noble and royal lines . . . but be careful. Not only are they addicting, but preserving the family history and genealogy of our less-exalted grandparents should not be forgotten. With lineages that have found their way into published books a century or two ago, it is important to verify every step of this path back in time to avoid “confirmation bias.” There are lots of errors that are copied repeatedly. Try to prove your hypothesis wrong as well as correct. Don’t ignore illogical pieces of information.

Demographic studies and population mathematics suggest that everyone alive today undoubtedly descends from the highest and the lowest echelons of past societies. Probably a few million people can or could “prove” specific lines of descent from royalty, with names in each generation. It is worth trying to prove it, as it can bring history alive when you see yourself in it.

Since your own descent from royalty will probably pass through generations of gentry, it is important to understand just who they were. What constituted the gentry class was different over its 600 or so years of existence. Terms like gentleman and esquire eventually were applied to people much more broadly than they were long ago. As the middle class and professional class grew, more and more people put “gent.” or “Esq.” after their names.

Were your ancestors members of the landed gentry? In 1873, 55% of England’s land was owned by the gentry. Your ancestors were upper gentry if they had several of the following characteristics. They . . .

● were baronets, knights, esquires, or simply “gentlemen.” They often had a coat-of-arms and in the 1500s and 1600s their pedigrees were recorded in the Heralds’ Visitations. Perpetuating their surname down the generations was very important and they enjoyed much social prestige and deference.

● held estates of 1,000 acres or more, often with a mansion house or “seat” in the shires. They did not perform manual labor, but lived off of rents of their tenants, and visited London frequently where they might have a second residence.

● practiced primogeniture, where the eldest son received the father’s primary landed estate.

● might be a member of the professions. Second sons often went into law, third sons into the church, fourth sons the army or navy, though the order varied. Some sons could be apprenticed into the more prestigious trades. Younger sons and younger daughters were provided with annuities.

● were educated in elite “public” schools, universities, Inns of Court, etc.

● worked hard to preserve the descent of their estate to heirs using dynastic strategies of intermarriage with cousins, entails, marriage settlements, strict settlements (to prevent profligate heirs from selling off lands) and mortgages (to raise capital). Their lineage can be traced through land deeds, sometimes over several centuries.

● were typically obsessed with rank and were sometimes snobbish, particularly with regard to upstarts who tried to join their ranks. Those who made their wealth in urban trade or international commerce, or the “nabobs” who came into fabulous fortunes in the service of the East India Company, were at first viewed with suspicion. Office holders and servants of the Crown or of the titled nobility were fashioned as “gent.” and sometimes accumulated much wealth as a side benefit of their high positions.

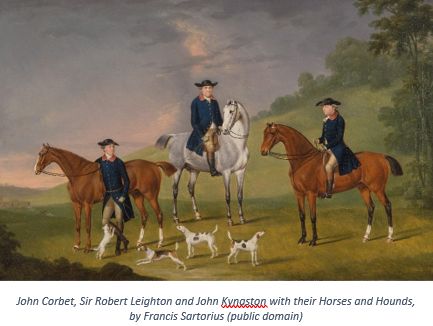

● had to pay taxes for their land, armorial bearings, carriages, silver, carriage and racing horses, servants, dogs, and clocks and watches. Their names are found on the freeholder lists of voters, and they signed oaths of loyalty and protestation, particularly if they wanted to serve in official positions.

● comprised the upper gentry and the minor gentry. The upper gentry or “county families” held county and national offices such as Justice of the Peace, Sheriff, Lord Lieutenant, or Member of Parliament. They held the advowsons or right to appoint local clergy to their “living.” The minor or parish gentry, who held a few hundred acres, filled local or parish positions like churchwarden, vestryman, overseer of the poor, Hundred constable, juror, etc. Men referred to as yeoman or husbandman were not gentry, but sometimes they aspired to it.

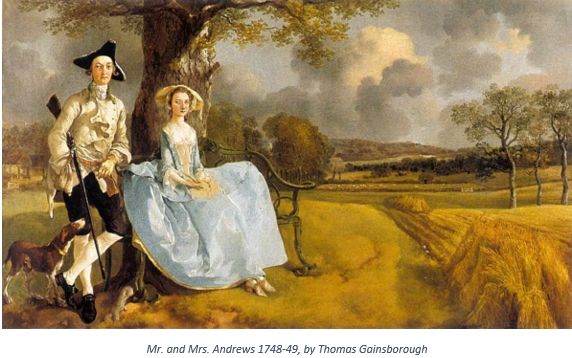

● rode to the hounds, entertained frequently, and went on Grand Tours of the Continent.

● invested in mining for coal and iron on their lands, in banking and shipping, and in colonization with the great trading companies (sometimes serving as directors).

● grew dramatically in numbers as monastic lands were sold off after the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid-1500s. Some families were created by successful textile manufacturing or from international trade.

● were litigious, with many suits in the Courts of Chancery or Exchequer, and in the Court of Common Pleas. Their estates were often controlled by trustees, and the estate “owner” may have really been a “tenant for life” under an entailment.

● were “lords of the manor,” which was not a title of nobility, but it conferred local prestige.

● buried inside the churches, sometimes with large sarcophagi, effigies, monumental brasses, or at least memorial plaques on the walls.

● probated their wills in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury or the Prerogative Court of York, usually because they had widespread property in different dioceses, or because there was more prestige to do so. They married by a license from a bishop so that banns would not have to be called.

● experienced a period of significant loss of wealth, power and status with the agricultural depression of the 1870s and the changing nature of the economy away from the land. By the 1900s, a broadening electorate was determined to distribute wealth more equitably, including with ever increasing death taxes. These made it harder to maintain large mansion houses, so many families devised their estates to the National Trust.

A list of sources for the gentry would go on and on, but here are a few key ones:

● The 1870s publications of Return of Owners of Land.

● Published pedigrees in the British Library, Society of Genealogists, Family History Library, Library of Congress, Google Books, Internet Archives, etc. Lists of pedigrees are found in a volume by G. W. Marshall (The Genealogist’s Guide), with updates by J. B. Whitmore and G. B. Barrow. Stuart A. Raymond has published many listings of county bibliographies and family histories, as well as bibliographies of indexes to periodicals.

● In addition to numerous “visitation pedigrees,” old publications feature many gentry families—Ancestor, Collectanea Topographica et Genealogica, Topographer & Genealogist, Genealogist, Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica.

● Creations of baronets, official appointments, formation and dissolution of business partnerships can be found in the London Gazette and in The Times. The British Newspaper Archives is invaluable to understand your ancestors in their social context.

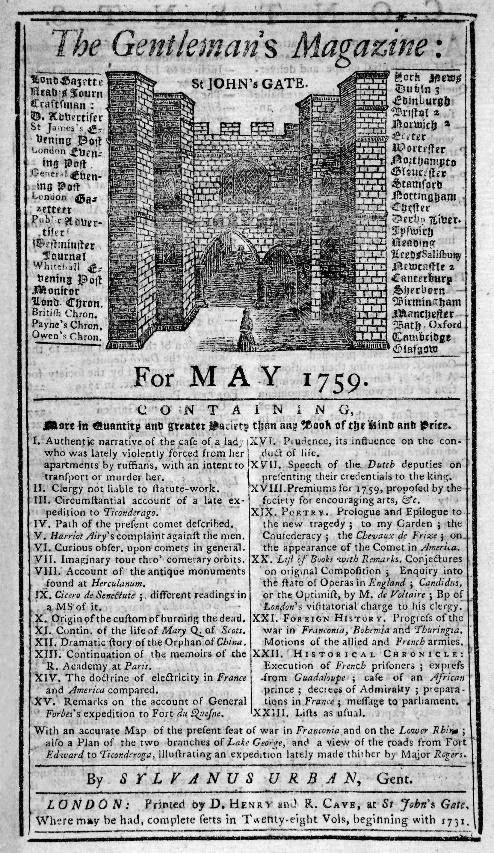

● The Gentleman’s Magazine ran from 1731 to 1907 and it was specifically published with the gentry and noble classes in mind. There are numerous items included of genealogical value.

● The Gentleman’s Magazine ran from 1731 to 1907 and it was specifically published with the gentry and noble classes in mind. There are numerous items included of genealogical value.

● Biographical dictionaries such as the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, the Biography and Genealogy Master Index, Who’s Who, and Who Was Who, etc. Also, Edward Walford’s The County Families of the United Kingdom or, Royal Manual of the Titled & Untitled Aristocracy of Great Britain & Ireland. Alumni registers for the universities and for important “public” schools are also available.

● A great blog that offers narratives on important gentry families is “Landed Families of Britain and Ireland” (https://landedfamilies.blogspot.com/) by Nick Kingsley.

● The subscription website “Burke’s Peerage” (https://www.burkespeerage.com/) is excellent. Younger sons and daughters of noble families descended into the gentry.

● For the many volumes of Burke’s Landed Gentry, see the Wikipedia article “Burke’s Landed Gentry” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burke%27s_Landed_Gentry).

● Debrett’s Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage, and Companionage is a well-known publication that covers the gentry and nobility. For a couple online editions of this book, as well as other relevant books, see “Pedigrees of The Peerage and Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland.” (http://peerageandgentry.com/). Several editions of Burke’s Landed Gentry are found here, as well as Edward Walford’s The County Families, which is mentioned above.

● The Harleian Society (https://harleian.org.uk/) published many of the visitation pedigrees.

● In the FamilySearch Wiki article, “England Records of Noble and Armigerous Families (National Institute)” are several useful references, including to Cecil R. Humphery-Smith’s Armigerous Ancestors and Those Who Weren’t; a Catalogue of Visitation Records Together with an Index of Pedigrees, Arms and Disclaimers. Also, on the same Wiki is “England, Titled and Landed Families (National Institute).”

● Don’t forget the extensive collections in county record offices, The National Archives (TNA), and elsewhere, of land and estate records, including deeds, surveys, leases, rentals, feoffments, bargain and sales, quitclaims, fines or final concords, lease and releases, common recoveries, mortgages, settlement, enclosure awards, tithe apportionments, etc. Also, manorial court records are invaluable, many of which are listed in the Manorial Documents Register.

Happy hunting as you chase after your land-owning ancestors! Remember, Price Genealogy is always ready to assist you in your quest for illusive ancestors and their true life stories.

Greg