Family and Food

7

7Jan

As we finish off the last of the holiday leftovers and begin our new year’s resolutions, do we appreciate where the family recipes fueling our holiday menus come from? Both my parents have passed onto my siblings and I food-related traditions they grew up with, such as Grandma’s candied yams. As I’ve spent holidays with other relatives, I’ve noticed different Thanksgiving and Christmas foods brought by other sides of the family. New year’s resolution diets may restrict eating some of these recipes, but it doesn’t restrict the family memories or stories.

Can you think of a social event (excluding zoom) that didn’t include food? Food, whether it’s healthy or loaded with sugars, connects people. This connection extends between generations. Can you remember Grandma without remembering her cooking? How many of her recipes do you share with your posterity, or would you share if you had posterity? By doing this, you connect your posterity to Grandma, even those who never personally knew her.

What started as a school assignment for me turned into a personal connection with my great-great-grandmother, Mary Louise Kearney, who died decades before I was born. The assignment was to interview a relative about a deceased relative whom they knew, so I interviewed my great-aunt about her grandmother, my great-great-grandmother. My great-aunt was a child when her grandmother died, so her memories were from her early life. She told me about her grandmother’s mashed potatoes, describing them as lumpy and very buttery. I like to cook, and I like to eat  potatoes, so I decided to try replicating my great-great-grandmother’s mashed potatoes. I asked my great-aunt for the recipe, which her grandmother had never written. She cooked everything by throwing ingredients together until she got something that tasted good, much like how I usually cook. So, I took this approach to replicating my Mary Louise Kearney’s mashed potatoes. The next time my great-aunt came into town, I fed her my replica of “Grandma Kearney’s” mashed potatoes. She said they were similar to how she remembered them. It occurred to me that Grandma Kearney had been dead for over 60 years and her cooking was what was remembered about her. This shows how powerful the connection of food is. When I get the FamilySearch notification that it’s Mary Louise Kearney’s birthday, I celebrate by making her mashed potatoes. I have included the recipe at the end.

potatoes, so I decided to try replicating my great-great-grandmother’s mashed potatoes. I asked my great-aunt for the recipe, which her grandmother had never written. She cooked everything by throwing ingredients together until she got something that tasted good, much like how I usually cook. So, I took this approach to replicating my Mary Louise Kearney’s mashed potatoes. The next time my great-aunt came into town, I fed her my replica of “Grandma Kearney’s” mashed potatoes. She said they were similar to how she remembered them. It occurred to me that Grandma Kearney had been dead for over 60 years and her cooking was what was remembered about her. This shows how powerful the connection of food is. When I get the FamilySearch notification that it’s Mary Louise Kearney’s birthday, I celebrate by making her mashed potatoes. I have included the recipe at the end.

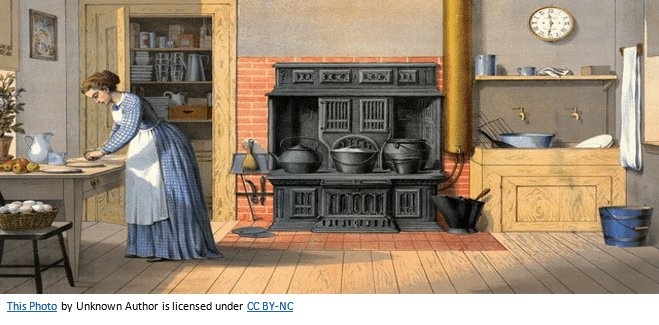

I’ve not researched my Kearney line as much as I’ve researched other lines in my family tree, but I grew up hearing stories of her family, and poked around that side of the tree enough to gain familiarity with her background. Grandma Kearney was born in New Jersey to Irish immigrants and married an Irish immigrant, Joseph McElhinney. Their son, John, is my great-grandfather, whom I knew as Great-grandpa growing up. He was already an old man by the time I was old enough to remember. Visits to Great-grandpa and Great-grandma were characterized by playing outside in the huge yard, sitting in the living room surrounded by books and magazines to read, and eating Great-grandma’s cooking, which typically consisted of meat and potatoes. On such a visit during my teens, when I was interested in romance stories, I asked Great-grandpa how he and Great-grandma had met. He told me how they met in college while playing ping-pong, described their college courtship, and explained how they married right after college, as was custom in that day for college sweethearts.

Great-grandpa going to college was its own story. He was a first-generation college student whose parents were poor. Grandma Kearney was either a maid or a cook; Joseph McElhinney was a chauffeur. (My great aunt told me they met while working for the same employer.) Great-grandpa’s teachers noticed his potential and encouraged him to pursue college, including doing well enough in high school to qualify for a scholarship. Thus Great-grandpa graduated college and became a nuclear physicist. My dad would relate this story to my siblings and I over family dinner, especially as he tried to encourage my sister and I to pursue STEM degrees. (My sister graduated with a chemistry degree; I considered STEM then went with genealogy instead.)

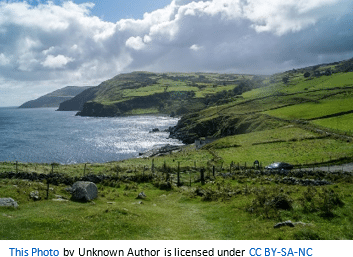

Joseph McElhinney’s story was also shared over food. Every St. Patrick’s Day, my dad would make Irish flag cookies and tell my siblings and I the story of Joseph’s journey to America. He had been a wagon driver in  Northern Ireland, and his family was protestant. When some Catholics needed a wagon, they decided to steal one from a protestant, who happened to be my great-great-grandfather. They beat Joseph and left him for dead and made off with his wagon. However, Joseph survived the attack and went home to his family. When his assaulters heard he survived, they gave him a one-way ticket to America, indicating they’d come after his family unless he went. So, Joseph came to America and made a life for himself here, and eventually met his wife, Mary Louise Kearney.

Northern Ireland, and his family was protestant. When some Catholics needed a wagon, they decided to steal one from a protestant, who happened to be my great-great-grandfather. They beat Joseph and left him for dead and made off with his wagon. However, Joseph survived the attack and went home to his family. When his assaulters heard he survived, they gave him a one-way ticket to America, indicating they’d come after his family unless he went. So, Joseph came to America and made a life for himself here, and eventually met his wife, Mary Louise Kearney.

Food, and the stories to go with them, have a power of connecting us to our ancestors. This connection can be very personal. After my brother died, my family would celebrate his birthday by eating a specific flavor of ice cream—Ben and Jerry’s Chocolate Fudge Brownie, which was the only ice cream my brother had tasted while he was alive.

A dear friend of mine, Jeffery, has lost his mother. Shortly after her death,  he really got into making her recipes, and had shared some of those foods with me. I never met his mother, but I could tell how much she meant to him by seeing his enthusiasm making her recipes.

he really got into making her recipes, and had shared some of those foods with me. I never met his mother, but I could tell how much she meant to him by seeing his enthusiasm making her recipes.

Jeffery made his mother’s banana bread, both with her favorite mix-ins and experimenting with new mix-ins. He made apple leather like she used to. He took her banana cake recipe and turned it into a banana ice-cream cake. He has also experimented with her pizza recipe and her chocolate éclair cake recipe (which she used to make him for his birthdays). Jeffery believes he is honoring his mother by cooking her recipes, even with his own twists added to them. Perhaps his mother would try these variations if she were still alive.

Jeffery is not the only one to modify family recipes with his own twists. I have added fresh fruit to my dad’s lemonade recipe and have given crazy names for each flavor. Susan Provost Beller, author of Roots for Kids, Finding Your Family Stories,[1] talks about her family’s Irish Soda Bread. The recipe has evolved until it’s only Irish in name, yet is still meaningful to her family. One modification is that the traditional raisins have been replaced with other dry fruit, then with frozen fruit. What matters is how meaningful the food is, more so than authenticity.

A metaphor can be drawn from this: we are who we are because of our ancestors, but we are each our own person. Learning about and connecting to our ancestors helps us understand the part of us we inherited from them.

Have you ever wondered what it might be like in the hereafter when we meet our ancestors? Will we have a family reunion? If so, will it involve food and what would we eat besides the family recipes which have been passed down through generations and modified with each new touch? When I meet Grandma Kearney, I intend to challenge her to a mashed potato cook-off.

Pull out the old family recipes. Tell your children of the relatives through whom their favorite foods come from. Learn the cultural foods of your ancestors and try cooking them. Take the family to a restaurant that represents an ethnicity you descend from. Most importantly, share the stories that make these foods meaningful. If you need help researching your ancestors’ lives and life stories, Price Genealogy can help.

Grandma Kearney’s mashed potatoes:

Ingredients:

- 4 large potatoes, peeled, chopped, and boiled

- 1 stick of butter

- Salt and pepper to taste

- Splash of milk

Directions:

- Combine potatoes, butter, and milk in a mixing bowl, smash with a fork

- Add salt and pepper, add more milk and butter if needed

- Enjoy

By Katie

[1] Beller, Susan Provost, Roots for Kids: Finding your Family Stories (Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company), p. 17.