Scottish Nonconformist Records

9

9Apr

The 19th century saw the creation of many useful genealogical sources for tracing our Scottish ancestors, including a national census in 1841 and compulsory registration of births, marriages, and deaths beginning in 1855. But before 1841, Scottish genealogical research relies heavily on parish, or church, registers, which began as early as 1551 when James Hamilton, Archbishop of St. Andrews, ordered the recording of baptisms and marriages. Very few burials were ever recorded. So today we're going to share with you how to navigate through Scottish nonconformist records.

Scottish Nonconformist Records

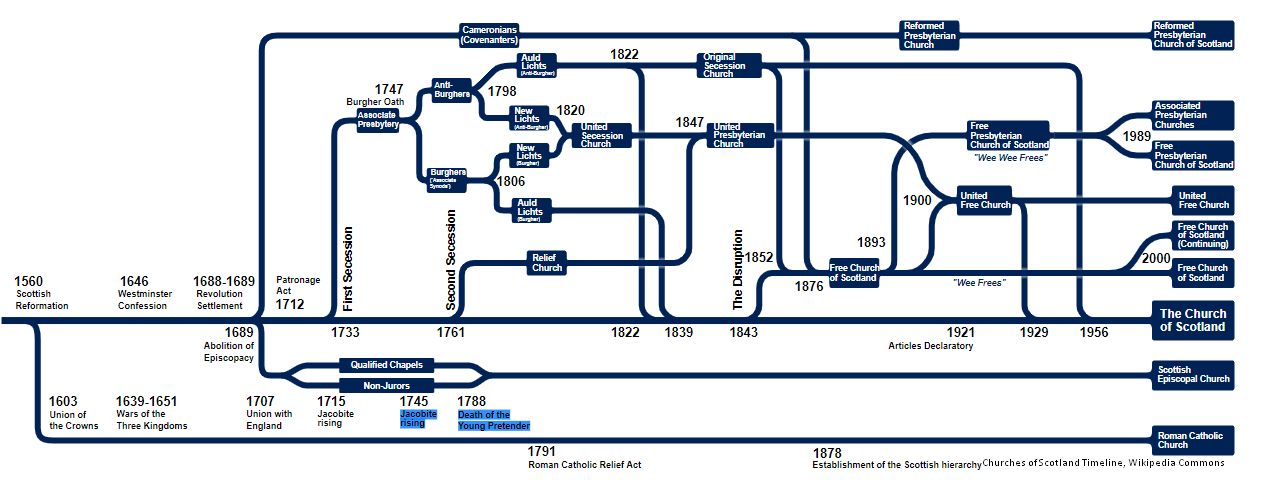

While England was undergoing its separation from the Catholic church under Henry VIII in 1534, Scotland was already many years into its dissent from the Catholic church, beginning in 1517 with Martin Luther. For decades, religious dissension persisted. By 1560 Scotland was declared a Protestant state during a time known as the Scottish Reformation, led by Calvinist John Knox (the ‘father’ of the Church of Scotland). But this was not to last long, with King James I establishing the Episcopal Church in 1610, which in turn was abolished in 1638 by Covenanters who swore to protect the Presbyterian Church. King Charles I and the English Parliament recognized the Presbyterian Church in 1641, but again in 1661 the Episcopal Church was established with the restoration of King Charles II. It wasn’t until 1690 that Presbyterianism became the recognized national church in Scotland.

Although it was the law in 1690 for everyone to belong to the new church, religious dissension was far from eliminated. Many of the secessions that subsequently occurred were rooted over the issue of patronage, or the right to choose the new minister when a vacancy occurred. The General Assembly of the Church ruled that the right to choose the new minister belonged only to the elders of the church or the local landowner (heritor), but many congregants felt the right belonged with them.

Secession churches

The first great split occurred in 1733 when four ministers left and formed the Associate Presbytery (or Secession Church). Not long after, in 1746 the ‘Breach’ occurred over a religious clause in the oath taken by the burgesses. The Associate Presbytery split into two groups: The Associate (Burgher) and the General Associate (Anti-Burgher). And in 1800, both synods had divisions again, into the ‘Old Lights,’ – those who believed secular authorities should uphold the actions of the church, and ‘New Lights’ – those who believed secular authorities had no power in matters of religion. The ‘New Lights’ from both Associate and General Associate came together to form the United Secession Church in 1820. And in 1839, most ‘Old Lights’ from the General Associate rejoined the Church of Scotland.

In 1761 the Relief Church split from the Church of Scotland, also due to concerns over patronage. It combined with the United Secession Church in 1847, creating the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland. The question of patronage was finally addressed in ‘the Disruption’ of 1843, when over a third of the Church of Scotland’s ministers broke away from the Established Church and formed the Free Church of Scotland. And finally, in 1900 the United Presbyterian Church merged with parts of the Free Church, which merged back into the Church of Scotland in 1929! And if that’s not confusing enough, there were also other religions present, such as the Cameronians, Baptists, Quakers, Scottish Episcopalians, Roman Catholics, Methodists, Congregationalist, Jews, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and others.

The following chart helps illustrate this confusing religious history in Scotland:

Researching the Records

When civil registration began in 1855, over two-thirds of Scots no longer belonged to the Church of Scotland. As such, the parish OPRs (old parish registers) recorded fewer and fewer of the population; however, some dissenters still chose to register births and marriages with the local parish. It is generally best to start research in the local Church of Scotland parish registers, including the kirk session records, both of which are available on ScotlandsPeople ($). If the ancestor does not appear, then turn to the records of nonconformist churches, which also kept records of births/baptisms, marriages, and at times deaths/burials, as well as occasionally minutes and lists of members.

One trick for identifying which nonconformist church they attended is to check statutory marriage records (after 1855), which will usually tell you the name of the church where they married. Dissenting congregations also sometimes had their own graveyards, so check monumental inscriptions. If the religion or church still is unknown, it becomes important to identify religious churches and congregations in the area where the ancestor lived.

Start by checking the Union List available through the FamilySearch Wiki. In the search field, enter the parish name and then scroll down to the list of nonconformist churches. A summary of identified nonconformist churches will be listed, along with any extant records and where they are deposited. If they have been microfilmed by FamilySearch, a link to the film will be provided.

The Statistical Accounts of Scotland or Groome’s Ordinance Gazetteer of Scotland will also list nonconformist churches in each parish. Keep in mind that each nonconformist church may have had a different boundary for their congregants which was not contiguous with the civil parish boundary. This is particularly true for Catholics, Quakers, Congregationalists, and Methodists. It may be necessary to search a wide area to accurately identify all of the churches in the area.

Some records have been microfilmed and are available through the Family History Library. Most are housed at the National Records of Scotland in Edinburgh (reference CH, previously called the National Archives of Scotland) or at university, county, or local archives. You can search for surviving records at the Scottish Archives Network website. It may be necessary to contact the minister of individual churches to determine where their records are deposited, especially for Baptist records. Unfortunately, many records just did not survive. Indexed records are available on ScotlandsPeople ($) and FindMyPast ($), as well as FamilySearch (Free) and Ancestry ($). For a list of some databases, search Steps for Tracing Scottish Ancestry Outside of the Church of Scotland on FamilySearch Wiki and scroll to the bottom of the page for a list of online records.

Do not assume that an ancestor stayed with a particular religion throughout their lifetime. As can be seen in the chart above, churches were being created and dissolved at an alarming rate in the 18th and 19th centuries, and many people associated with multiple churches throughout their lives. Keep an open mind, become familiar with the local history of your ancestral areas, and make sure to identify surviving extant records before relying solely on online databases.

Do you need help navigating Scottish nonconformist records or anything else? Let us know in a comment below!

By Emily

[Works Cited]

Adolph, Anthony, Tracing Your Scottish Family History. Firefly Books, 2009.

“Scotland Church History.” FamilySearch Wiki, 5 August 2020 : accessed 6 April 2021)

“Scotland Church Records.” FamilySearch Wiki, 19 March 2021 : accessed 6 April 2021).

“Scotland Church Records Union Lists.” FamilySearch Wiki, 21 January 2020 : accessed 6 April 2021).