Genetic Genealogy (part 4): Obstacles in DNA Research

15

15Jan

Are you interested in answering a genealogy question using DNA? Read this post about the most common obstacles with DNA research to watch out for and some ideas of how to overcome them

Overcoming Obstacles with DNA Research

Not Enough Matches

The key to solving genealogical problems with DNA is finding the right DNA relatives. But what happens when there are not enough DNA matches to begin with? Most people notice that one or two family lines account for most of their DNA matches, but if the family line you are researching has few matches, it can be very difficult to continue working the problem through DNA.

The first thing to consider doing is uploading your DNA to other databases. Check out some of our previous blogs for discussions about the various companies and their features. The two largest databases are Ancestry and 23andMe, however you cannot upload DNA to either of these websites. The only way to access their databases is to complete a DNA test with them. The companies MyHeritage, Family Tree DNA, and GEDmatch accept uploads of raw DNA for free, but require you to pay for some features. In the end, the more people your DNA is compared to, the better your chance of finding the right DNA relatives.

Sometimes the problem causing a lack of matches is geographical. For instance, when looking for European matches, uploading your DNA to MyHeritage and Family Tree DNA is a must because they have a more international focus.

In an ideal situation, there would be enough good matches to solve the research question without contacting anyone. However, if there are a lack of matches, contacting the ones you have is essential. A cooperative DNA relative can save you a lot of time and energy and can make all the difference when searching for a common ancestor.

If the problem is that no descendants of the family line in question have tested their DNA, consider hiring a professional genealogist to make sure the paper trail has been exhausted. Then, you may consider targeted testing, though it can be costly. Targeted testing means finding living individuals whose DNA tests could help solve the problem, then asking them, and in most cases paying for them, to take a DNA test. Targeted testing is mostly used when trying to find an unknown parent and after DNA matches have revealed a common ancestor between them and the unknown parent. The researcher finds and selects a living descendant of the common ancestor and asks them to take a test. With some DNA problems, you may already have a theory about the answer at the beginning of the process and targeted testing could help prove or disprove the theory. In this way, targeted testing may help you get around a lack of DNA matches.

Matches without Trees

It can be very frustrating to find a good match, one that could likely help solve the DNA question, but be unable to use them because they do not have a family tree connected to their DNA results. The value of a match often hinges on being able to find a common ancestor between you and the DNA match. Luckily, there are some workarounds for this problem. First and most obvious, attempt to contact them. Message them through the DNA database system or, if they have enough identifying information, try to find them on social media. If this does not work, consider using/signing up for a people search website and try to build their tree from scratch.

People do not realize how much of their information is public record. The value of people search sites like instantcheckmate.com or spokeo.com is that, not only do they gather and organize this public information, but they also use it to find related individuals. With exact birthdates, addresses, and related individuals, it could be possible to find the names of a DNA matches’ living parents and/or grandparents and then their deceased relatives going back from there. Between people search websites, social media, and Ancestry’s public record information, even DNA matches without linked family trees can be used to solve a DNA problem.

Many DNA matches will have usernames that do not include their actual names or only include a portion of their names. In this case, it may not be possible to build their tree using public record information. You can try username reverse search websites to see if you can find any identifying information, but you may still hit a dead end. Additionally, if they have an extremely common name with no further identifying information it also may not be possible to distinguish them in the public record.

Non-Cooperative Matches or Potential Matches

Sometimes, a person may refuse to cooperate with you in solving your DNA problem. This can be extremely disheartening, but understandable. The revelations that DNA can bring to family relationships are often emotional and complex. You may ask someone to take a test who does not want to be involved. Or someone may have tested simply to see their ethnicity results and they do not want to provide you any information because they do not want any DNA surprises. However, even a non-cooperative DNA match is not necessarily a dead end. Always be kind and respectful of a person’s privacy. But if possible, try using the public record as described above to find information on their family. If one person in a family says no to taking a test, consider asking someone else in their family like a sibling, nephew/niece, or cousin.

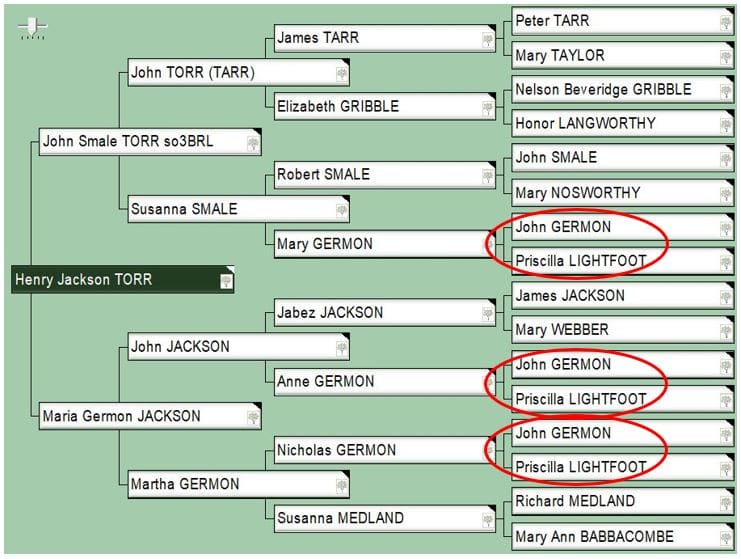

Pedigree Collapse

Pedigree collapse is a common obstacle in DNA research. It occurs when someone is related to an ancestor in more than one way. As an example, if your dad and your mom are related to the same ancestors, your dad through the ancestors’ daughter and your mom through the ancestors’ son, then you will have inherited DNA from those ancestors in two different ways. Normally, it is expected that someone has 8 completely unique great-grandparents, 16 great-great-grandparents, 32 great-great-great-grandparents, etc. But if your parents had some ancestors in common, then you might only have 14 unique great-great-grandparents instead of 16 and you would inherit more DNA from those two repeat great-great-grandparents than any of the others. This is pedigree collapse and when it occurs in your tree within the last 7-8 generations, it can be an obstacle, especially if you are not aware of it.

Pedigree collapse poses problems when trying to figure out how a DNA match is related to you. If, for example, you find a DNA match who shares enough centimorgans with you that they are likely a 3rd cousin, then you would try to find a common set of great-great-grandparents. But, if that match is related to you through the section of your tree that has pedigree collapse, they could be a 4th or 5th cousin and you would need to research further generations.

Look out for pedigree collapse in your family tree and be aware of its possible effects on how much DNA you share with cousins on that line. If you are not finding common ancestors between you and a DNA match where you would expect, then simply look for one in the next generation back. Keep in mind that even if you do not have any pedigree collapse in your tree, that your DNA match could, and it could cause the same problem.

Double Cousins

Occasionally, you may find a DNA relative who is a double cousin. This means that they share not just one set of common ancestors with you, but two sets. For example, you may find a third cousin (who normally shares one set of great-great-grandparents with you) that is related to you through two different sets of great-great-grandparents. In this case, they are double 3rd cousins and will likely share more DNA with you than any other third cousin in your DNA match list.

In most cases, you cannot look at your tree ahead of time and know that this is going to be a problem. For this reason, it is critical to be thorough when building out a DNA matches’ tree. If you easily found a common ancestor on one side of their tree but did not look at the other side of the tree, do not just assume that you are done. If they are a double cousin, they could have a common ancestor with you on the other side of the tree as well.

Endogamy

When a family tree has a great deal of pedigree collapse and multiple double cousins, it may be the result of endogamy. Endogamy is the practice of only marrying within a local community or clan. In DNA, the term implies that the practice occurred for many generations, thus affecting DNA inheritance. Like untangling a knotted rope, piecing out endogamous relationships in order to solve a DNA problem is extremely tricky.

When individuals only marry within a tight-knit community, it is more common for married couples to be cousins. If someone’s family tree has many sets of grandparents, great-grandparents, great-great-grandparents, etc. who were cousins to each other (could be 1st, 2nd, 3rd cousins, and so on), then there will be a great deal of pedigree collapse. Instead of 32 completely unique great-great-great-grandparents, you may only have 20.

It is common in endogamous populations for multiple people from one family to marry multiple people from one other family. Three brothers in one family, might each marry a sister in another family or three cousins from one family might marry three cousins from another family. This makes it far more likely to encounter double cousins in your DNA match list.

When endogamy occurs, the typical pattern of genetic inheritance gets altered. Normally, you inherit an average of 6% DNA from a great-great-grandparent. This number always fluctuates, but when endogamy enters the equation, the fluctuation becomes much greater. With enough pedigree collapse resulting from endogamy, you might have two or three times as much DNA than normal from one set of ancestors. Plus, you will likely find double or triple cousins who also inherited an above average amount of DNA from their ancestors. Puzzling out these relationships can be extremely daunting and make solving a normal DNA mystery extremely difficult.

In these situations, it is often necessary to hire a DNA expert to help with the problem.

Conclusion

Watch out for these potential obstacles in DNA research. Experiment with the suggested workarounds for matches without linked family trees and uncooperative individuals. Be thorough and pay close attention to any inconsistencies between shared DNA and the closeness of the relationship. If you found a third cousin who shares far more than the normal amount of DNA, look for pedigree collapse, a double cousin relationship, and endogamy. As always, our DNA experts at Price are willing to help at whatever point you find yourself in your genetic genealogy journey.

-Forrest

Have you ever experienced obstacles with DNA research before? Let us know in a comment below!