Tracing Hispanic Roots in Mexico and Spain

26

26Apr

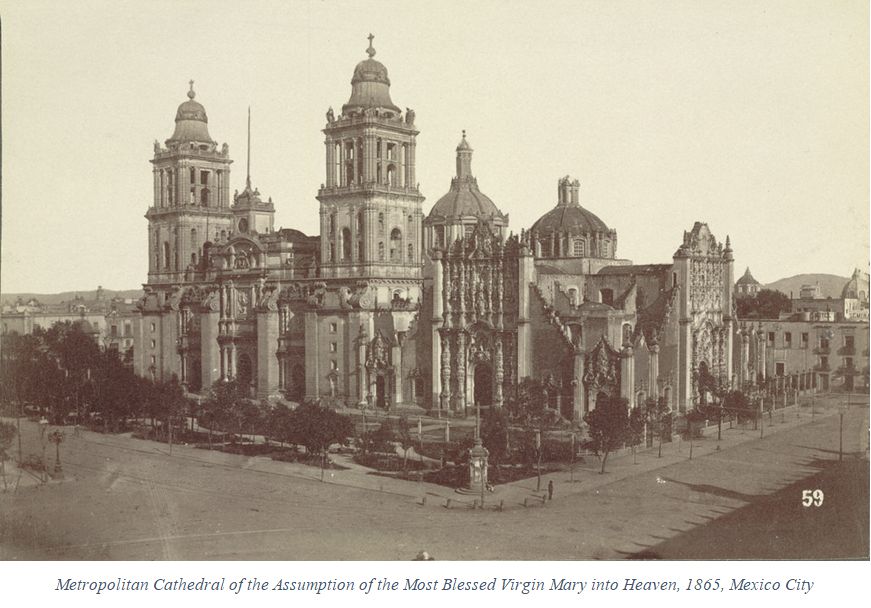

With Cinco de Mayo coming up, this is a good time to write about Hispanic genealogy. For those interested in their Hispanic genealogy, they will often question just how complex or challenging it is to trace Mexican and other Spanish roots. As more records for these areas become available, it is natural that hope of success is increasing. Both countries share many things in common, including the Spanish language, similarities in food, culture, and even genealogical record types. Mexico was formerly a colony of Spain. Hernán Cortés led an expedition in the year 1518 to what is now Mexico, and the area fell to Spain’s control in 1521. Mexico gained independence in 1821 with the signing of the Treaty of Cordoba. This year is important for Hispanic genealogy because it determines where to find the records for your ancestors.

Understanding jurisdictions is important for all genealogical research. Spain, for instance, is divided into fifty provinces and each of these is part of one of seventeen self-governing communities. Mexico is divided into thirty-two jurisdictions: thirty-one states and a federal district. It is important to know the jurisdiction your ancestor lived in. You can sometimes find their original location on documents tucked away in your home. A death certificate, obituary, marriage certificate, or even the birth certificate of one of their children may identify a birthplace. Ancestry’s DNA test can often indicate the states in Mexico where your ancestors originated. This test shows a greater level of geographic specificity than is typical for some regions. Other records to consider are immigration and citizenship papers. After 1906, these should provide your ancestor’s specific town of origin.

Useful collections include:

• United States Border Crossings from Mexico to United States, 1903-1957, located on FamilySearch.org.

• U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, located on Ancestry.com.

• USCIS immigrant case files (for those naturalized after 1906), must be ordered from USCIS (not available online). See their Genealogy Program. However, there are naturalization records available online for the period after 1906. For instance, see Ancestry’s “U.S., Naturalization Records, 1840-1957.” This contains images of Declarations of Intention and Petitions For Naturalization. There are a lot of post-1906 indexes to naturalizations on Ancestry as well. A perusal of the FamilySearch Catalog under “Naturalization and citizenship” will show a large number of collections of naturalization records, many continuing well beyond 1906.

• Because some place names and boundaries have changed, or no longer exist, using an old gazetteer may help locate the record collections. FamilySearch holds several volumes of gazetteers for Spain. A gazetteer for Mexico can be found here and is searchable by city.

Another important aspect of identifying an ancestor are the names they were given at birth. Both Mexico and Spain have naming customs. Generally, a baby’s name consists of three parts. The first part is called a given or forename. Until the 1960s it was often the custom to baptize children with three forenames. The second and third parts are the two last names, also called surnames. The first surname (last name) is commonly that of the father, and the second surname is that of the mother. A great example of this naming custom is from the famous painter, Pablo Ruiz Picasso. Pablo was his first or given name. Ruiz was his paternal surname or father’s last name. Picasso was his maternal surname or mother’s last name.

Sometimes a name consists of several parts and it is hard to decipher correctly. There was a writer known as Sebastià Juan Arbó, and he was alphabetized in the archives of the Library of Congress for many years under the last name of "Arbó." It was assumed that Sebastià

and Juan were his first name. But "Juan" was not a first name. It was actually his first surname. When researching in the English archives, the Chicago Manual of Style, fifteenth edition, recommends that Spanish names be indexed under the father’s family name, being the first element in the surname. Not knowing this could cause a person to mistakenly match an ancestor with the wrong record.

The majority of the people in both countries are Catholic. The church records play a vital role in researching your ancestors. Catholic records have been kept in Spain since the mid-1500s. In Mexico, church records began as early as 1527. Catholic collections include at least five types of records: baptism, confirmation, pre-marriage investigations, marriage, and burial information. The Catholic church was the primary record keeper for Spain until 1869, and in Mexico until 1859. Civil registrations began in Spain in 1869/1871 and in Mexico in 1859. If you are researching an ancestor after the year civil registration began, it is best to look in both the civil and church collections. It is important to note that dioceses were established in different jurisdictions at different points in time. For example, in Mexico, the Diocese of Oaxaca was established in 1535, while the Diocese of Durango was established in 1891. In Durango, if you were researching an ancestor who lived in 1850, you would need to know which diocese was keeping the books prior to 1891.

A list of parishes in Mexico can be found here. As of the writing of this article, FamilySearch lists sixty-six collections for Mexico in their Historical Record Collections web page. These include almost all thirty-two jurisdictions mentioned earlier, and typically include both the Catholic church records, and the civil registration (government birth, marriage, and death records). Most of the civil registration records have been indexed, but most of the Catholic church records have not. The indexed records are also searchable on Ancestry, and some records may be more easily discovered on their website due to differences in how searches are handled. For the unindexed records it is critical to know a specific parish to search so that the records can be examined page-by-page. This makes research before the introduction of civil registration more difficult, unless your family happens to be covered by the small percentage of Catholic records that are indexed.

A list of dioceses in Spain can be found here. A few links for church records in Spain, located on FamilySearch include the following.

• Spain Baptisms, 1502-1940

• Spain Marriages, 1565-1950

• Spain Deaths, 1600-1920

For both countries, there are many records that exist only as originals or microfilms in specific archives (not online). Much of the western United States belonged to Mexico until the mid-1800s, and some older Mexican records will even be found at archives in this part of the United States. For example, an important collection of early Durango Diocesan Catholic records is held in New Mexico State University’s Rio Grande Historical Collections.

A collection of records that is often overlooked, but very valuable are the notarial records. The documents found among notarial records include: wills, guardianships, dowries, mortgages, purchases of goods or land, and agreements or settlement records. Very few of these records have been indexed for Mexico. However, some of them may be found in the Mexican National Archives or can be obtained by writing the local jurisdiction. In Spain, the notarial records were the second-best place to learn what was happening in a town or jurisdiction. The first place being the church records. The key to using notarial records is knowing where your ancestor accessed the notaries. If an ancestor lived in a small town, they may have traveled to a nearby larger town to find one. If an ancestor already lived in large town, they could have used a notary nearby. But it was not uncommon for them to use a notary with a strong connection to their family, even if it meant traveling to see them. Most of the provinces in Spain have lists identifying the notaries and the years they were in service to that community. A good resource for locating the notarial records in Spain is the PARES site. There are even more archival websites and portals that are important to tell the stories of our ancestors, especially where church records are unavailable, or to uncover more information than is possible in church records alone. For Mexico click here, and for Spain click here.

Researching ancestors in Spain and Mexico can be complex. First, the area the ancestor lived must be identified. Second, the person’s name is very important. It is very easy to connect a family member to the wrong records, if the naming components are deciphered incorrectly. Knowing the diocese—and often the parish—that recorded the family records is vital for researching families in Spain and Mexico. The notary that families used can be very beneficial, but they can be difficult to identify. Also, knowing how the records are indexed can affect your research. If you discover you need help, the experts at Price Genealogy are ready to assist you with tracing your Hispanic ancestry.

Billie and Michael