Tax Records:The Secret Gem of Early American Records

5

5Nov

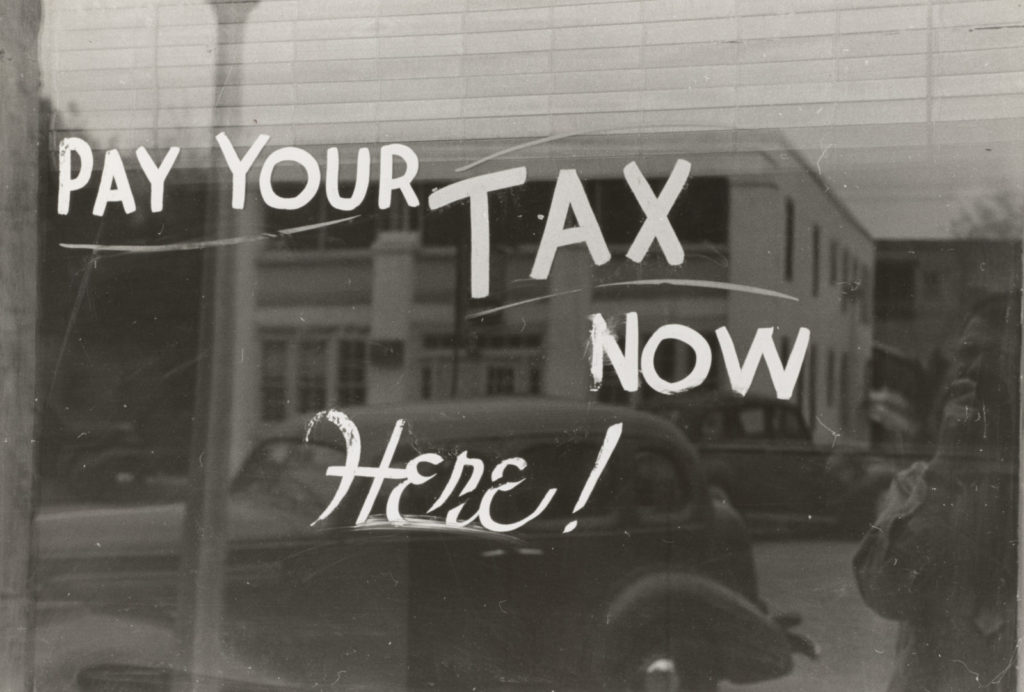

It was Benjamin Franklin who coined the memorable phrase, In this world nothing can be said to be certain except death and taxes. His sentiments were true, though how fortunate we are as family historians that these records have practically been in existence since the beginning of civilization. Tax records are one of the oldest historical records available and for American research they date back to colonial times. Unfortunately, this genealogical gem is commonly overlooked, likely because of its rather dull reputation. Such a pessimistic view could not be further from the truth! Tax records often hold the keys to a gateway of exciting family discoveries.

Types of Tax Records:

Municipal taxes were typically collected at the county level, often organized by districts or townships within the county. In general, three different types of municipal tax records are available to genealogist. They are (1) Poll Tax—also referred to as a Head Tax, a tax collected from every adult male regardless of their financial resources; (2) Real Property Tax—a tax collected on the amount of land/real estate a person owned; and (3) Personal Property Tax—a tax levied on one’s personal income and assets.

Prior to the twentieth century, the Federal government would also occasionally tax its citizens. “There are three federal tax record groups that can provide genealogical researchers with specific tax information about their ancestors: the records of the Direct Tax of 1798; the Direct Tax of 1861…; and the Income Tax of 1862-1872.”[1] Though infrequent, the collection of tax by the federal government reveals unique challenges faced by a newly established nation. For example, the Federal Direct Tax of 1798 was implemented as a way for the government to raise funds for a possible war with France. This tax was aptly nicknamed the “Window Tax,” as it listed the number of window panes in each house valued over $100.

Genealogical Information & Limitations:

Tracing one’s ancestors in tax rolls can offer fantastic clues about a family’s history. These records are typically arranged by township/district within a particular county. If your ancestors are not listed in alphabetical order by surname, then the people entered before and after them on the rolls were likely their neighbors. Gleaning details from these rolls will provide clues to parentage, birth and death years, marriages, arrivals and departures from a county, as well as their occupations. Tax records can also bring clarity to two people with the same name in the same county, provide insight into the socio-economic position of a family within the community and shed light on who their neighbors were. Tracking your ancestors in tax records, year by year, can bring clarity to genealogical details that are often lacking between the decennial enumerations of the federal census.

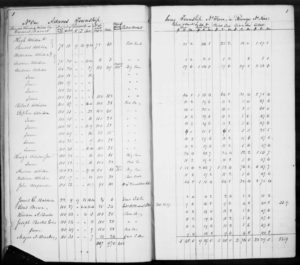

Alas, tax records are not without their limitations. The bulk of entries on the tax rolls are for adult white males only—children, females and those of varying ethnic makeups were typically not listed. Unfavorable storage conditions over time have compromised the quality and preservation of some lists. Challenging penmanship and unusual column formatting adds another element of difficulty in readings these records. Many counties have not digitized all of their tax collections; hence, a researcher must probe these old ledger books on-site or pay someone to do it for them. Furthermore, locating ancestors can be a challenge with changing jurisdictional boundaries, as well as understanding contemporary tax laws and collection requirements.

State, canal, school, poor, road & town taxes: Adams Twp., Washington County, Ohio, 1838; “Ohio, Tax Records, 1800-1850,” FamilySearch, image 7 of 834.

Where to Find the Records:

The best place to start identifying your ancestors in tax records is the Family History Library Catalog. This catalog can be searched by location. For municipal tax records, an ancestor’s state and county of residence must be known. It is even better if the township or district can be identified. Besides the Family History Library Catalog, on-site county records—at the local court house and/or historical society—should also be explored. State archives can also house tax rolls. For Federal taxes (such as the Direct Tax of 1798) the National Archives and Records Administration has detailed listings of their holdings. Lastly, Ancestry has over 90 tax lists databases in their U.S. collections that can be searched by name and location.

Investing your time and energy to explore tax records can bring abundant results to your genealogical endeavors. These underutilized historical records comprise details about your ancestors that are often unattainable through other research avenues. As Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. stated, I like to pay taxes. With them, I buy civilization. For the genealogist, we are grateful our ancestors paid taxes, because with those tax lists we can break through our brick walls!

Cara

Several expert genealogists with Price Genealogy can help you extend your ancestral lines using tax records and many other sources. You will receive a full research report, summary, recommendations, research log and document images. We can also update your genealogy database, FamilySearch Family Tree, Ancestry’s Member Tree, etc.

[1] Carol Cooke Daxxow and Susan Winchester, The Genealogist’s Guide to Researching Tax Records (Westminster, Maryland: Heritage Books, Inc., 2007), 94.