Finland Genealogy Research – Part One

8

8May

Finland is a beautiful country with the most wonderful, open and sincere people you will ever meet. Finland has a rich cultural heritage and history, with deep ties to Sweden and Russia. Lucky you, if you have Finnish roots. You most likely have inherited SISU, a Finnish concept described as stoic determination, tenacity of purpose, grit, bravery, resilience, and hardiness.[1] SISU is an element that Finns themselves express as their national character. So, for all of you with Finnish ancestry, we are excited to share with you today how to navigate through Finland genealogy work.

Finland is a beautiful country with the most wonderful, open and sincere people you will ever meet. Finland has a rich cultural heritage and history, with deep ties to Sweden and Russia. Lucky you, if you have Finnish roots. You most likely have inherited SISU, a Finnish concept described as stoic determination, tenacity of purpose, grit, bravery, resilience, and hardiness.[1] SISU is an element that Finns themselves express as their national character. So, for all of you with Finnish ancestry, we are excited to share with you today how to navigate through Finland genealogy work.

It is not difficult to do genealogical research in Finland, but in addition to the basic skills of genealogical research and history, one needs to have some elementary knowledge of the Finnish (F) and Swedish (S) languages. Getting familiar with these languages, along with naming traditions, can be intimidating. Once you get a handle on them, however, you will find success in Finland’s well-preserved records.

FINLAND GENEALOGY

When doing Finnish research, it is important to know how the Finnish names were used and developed. When coming to North America, names were transformed in a certain manner. Having this knowledge can help genealogists understand how the Finnish names were changed and reconstructed.

Finland did not become an independent country until 1917. From around 1150 until 1809, Finland was a part of Sweden. Most of the records during this time period were in Swedish. When Russia defeated Sweden in the Finnish War in 1809, Finland became part of the Russian Empire. Under Russian rule, Finland had more autonomy, and Finns developed a stronger sense of their national identity.

Finland is divided into two different cultural areas: the eastern and the western. In the east—influenced by Russia, with the Eastern Orthodox faith and in the west—influenced by Sweden, with the Roman Catholic faith, and later the Lutheran, names are evidence of these cultural differences:

- Eastern Finnish Name

A heritable surname system has been in use in Eastern Finland for centuries. A son-in-law accepted by the family could get the name of his father-in-law. Women generally just kept their fathers’ name, even if they were married. Eastern Finnish names had endings such as -nen or -inen as in Kekkonen, Laukkanen, and Koponen. The names of women usually had the ending -tar or -tär: Kekkotar, Laukatar, and Kopotar.

- Western Finnish Names

The western cultural area was, as previously mentioned, closely connected to Sweden. Family names were not used in Sweden. People were identified by a combination of a given name and a father's name, a patronymic. A patronymic is formed by attaching an ending to a given name (-poika/-tytär (F)) and (-son/-dotter (S)). In Finnish, an n was added between the father’s name and the suffix. A woman’s patronymic name did not change when she married. For example:

-

- (F) “Karl Taavetinpoika” is “Karl, the son of Taavetti” and (S) "Olof Johansson" is "Olof, the son of Johan." In three generations, there may be a chain:

-

-

- (F) Taavetti Jaakonpoika (grandfather) > Karl Taavetinpoika (father) > Anna Karlintytär (daughter)

- (S) Per Nilsson (grandfather) > Johan Persson (father) > Maria Johansdotter (daughter)

-

During the last half of the 1800's and the start of the 1900's most people in the western parts of Finland accepted family names and started to use the farm name as a family name. It can be difficult to distinguish a family name from a farm name. The difference between the two is that family names are inherited to younger generations, while farm names change when individuals move from one farm to another. Farm names generally have an ending -la or -lä as in Anttila or Siirilä.

Soldier Names

To separate all the men with similar names (given name + patronymic) a law stated that soldiers should have distinct additional names. The names were mostly short and easy to pronounce. A couple of examples are Harnesk (armour) and Trumpet (trumpet).

Craftsmen

Craftsmen living and working in towns had to use family names. Typical parts of the names are -berg (rock), -lund (grove), etc. Lindqvist and Forsvik may be family names adopted by craftsmen.

The Virtanen Type

Family names were reminders of the old names of the eastern type, commonly constructed with the first part of the names usually from nature: Virtanen (virta=stream), Nieminen (niemi=point), and Suominen (Suomi=Finland). Most of these were adopted from 1900 to 1910.

Family Names Act

In 1920, three years after its independence, Finland passed the Family Names Act. This act standardized Finnish surnames, requiring everyone to use family surnames.

HOW TO GET STARTED

Start with what is known. Find out as much information as you can find from your family and living relatives, which may include family traditions and oral histories. Compile names, dates of birth and death, marriages, place of residence, and occupations. Especially look for records that contain information that may list places of residence in Finland such as,

- Birth, marriage & death certificates

- Family Bible information

- Cemetery / sexton’s records

- Obituaries & newspaper clippings

- Letters & documents from the “Old Country” / diaries

- IDs / passports

- Parish Membership Transfer Certificate(s): Utflyttningsbetyg (S) Muuttokirja (F)

- Old photographs & postcards

- Land records

- Military records

- Membership records of associations & organizations

Naturalization records should be sought after. They may not list the place of origin in Finland, but usually the arrival in America and often the name of the ship and port of arrival. Many Finns who came to the United States wanted to become citizens. While citizenship was not required, many Finns chose to become naturalized to vote, hold elective or appointed office, or qualify for land under the Homestead laws of 1862. The vast majority were naturalized through the county court system.

If you still can’t fine your ancestor’s birth date, start with a more recent generation because eventually you will need the hometown, village, or church parish from which your immigrant ancestor came. Here are a few databases that may help you find a place (farm, village, parish) in Finland:

- HisKi Project (http://hiski.genealogia.fi/historia/indexe.htm)

- FamilySearch’s online Finnish collection (https://tinyurl.com/tjoqvfe)

- com (https://tinyurl.com/vkys2ft)

- com (https://tinyurl.com/rf9bkft)

FINNISH RECORDS

Jurisdictions

Places are usually written from smallest to largest.[3] For Example:

Ala-Temmes, Liminka, Oulu, Finland

(Village) (Parish) (County) (Country)

Ala-Temmes is a village in Liminka Parish in Oulu County in Finland.

Church Records (Kirkonkirjat (F), Kyrkoböcker (S))

Once the home parish has been located, you will find the Lutheran Church records are some of the very best in the world. For the parish where your ancestor lived, you will search these records: birth (födda/e (S), syntyneet (F)), marriage (gifte (S), vihityt (F)), and death (döda/e, (S), kuolleet, kuoli (F)) and Communion Books (Kommunionböker (S), Rippikirjat (F)). They are organized by village (by (S), kylä (F)), and therein by farm. Over time, some parishes have been divided and borders have been changed. The earlier records of a particular parish may be found in its “mother” (previous) parish. The farm owner appears first with all other residents of the farm listed after him. Listed in these books will be relationships, dates, other vital information.

Other types of parish records include baptisms, confirmations, banns, membership transfers, parish minutes, burials, and moving in and out records, etc. Military and court records also exist.

RESEARCH PROCESS

The basic research process involves moving back and forth between birth, marriage, and death records and the Communion Books. Two main sites for the Finnish records are Finland’s Family History Association (FFHA, https://tinyurl.com/v8o49a8) and Digihakemisto (https://tinyurl.com/ux277c4). The following is an outline of the research process:

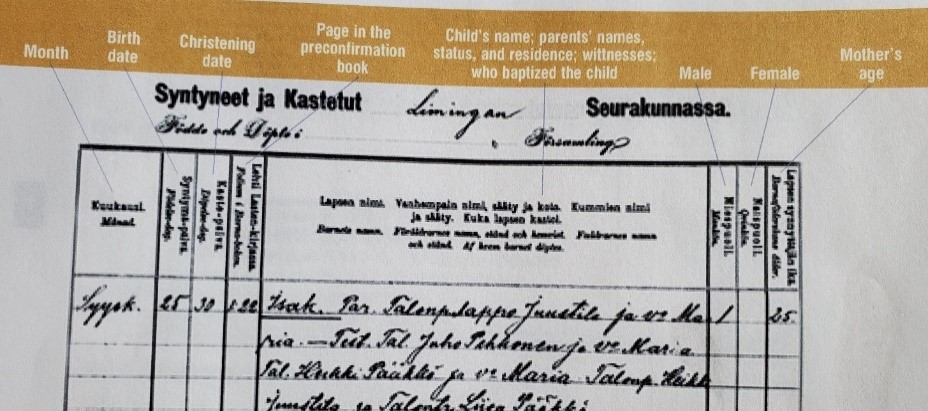

- Step 1: Using the birth books, find the birth date and the names of the parents of your ancestor. Record the name of the father, mother, and the farm and village where the family was living at the time of the birth. Also record any abbreviations that may be in front of the father or mother’s names and list all witnesses. Be sure and record film/fiche/book numbers, page numbers, entry numbers, and any other identifying information. Use maps and gazetteers to identify all places. Example of a birth record is listed below.[4]

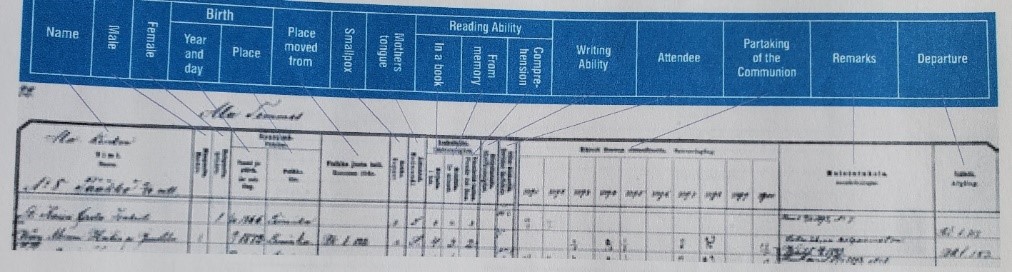

- Step 2: Find the family in the Communion Book.[5] Using the village name and farm name from the birth record, find the farm in the Communion Book that covers the year of birth of the child you just found in the birth records. Record everything, siblings, parents, grandparents, along with dates and places. Continue to find the family in every Communion Book, do not skip any time frames or records.

- Step 3: Find the names and birth dates of siblings. Use the birth records to confirm the information you find in the Communion Books. Also use the parents’ names and the names of the farm and village where the family lived to find the birth dates of other members of the family.

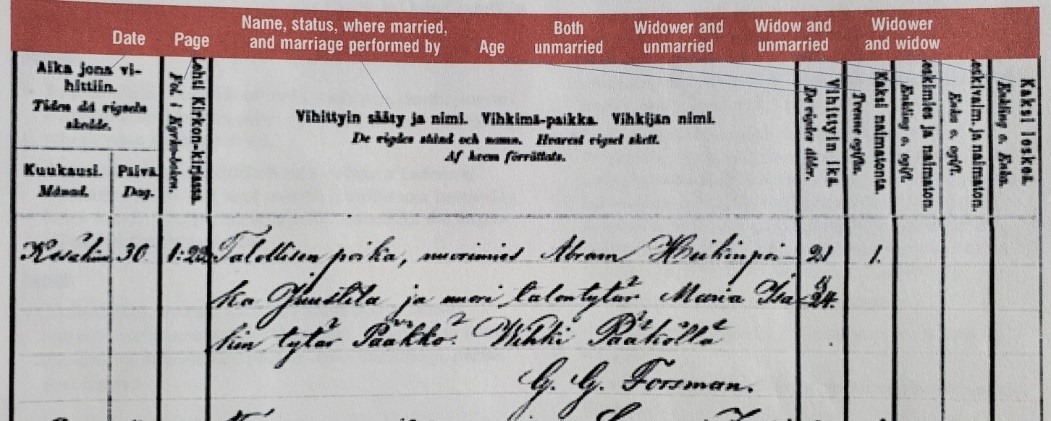

- Step 4: Find the marriage date of the parents. Look for the marriage of the parents, prior to the birth of the first child. Below is a marriage entry example.[6]

- Step 5: Find death dates. Follow the Communion Book records forward in time to determine the death dates of family members. Confirm with actual death records.

- Step 6: Repeat the process for the next generation. Repeat the process for the parents of the individual with whom you started in Step 1. Using the birth dates from the Communion Book, find the parents (as children) in the birth records. This will give you the names of grandparents, and the villages and farms where the grandparents were living when the parents were born (“Step 1” again). Find the grandparents’ farms in the Communion Books (“Step 2”), etc.

LANGUAGE HELPS

Do not let those Swedish and Finnish terms frustrate you. There are enough tools available to help you understand Finnish documents. Here are a few to get you started:

- net (https://tinyurl.com/y67wroj6)

- FamilySearch’s Finnish & Swedish genealogical word lists (https://tinyurl.com/r5dyvpo (F), https://tinyurl.com/r8lndcm (S))

- google.com

CONCLUSION

This is part one of a two-part series on Finnish genealogy research. Part two is a more detailed listing of online resources that can help you with Finnish research. Remember, the more research you do, the more you will gain a better understanding of the Finnish documents.

Stacy

[1] “Sisu,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sisu, (accessed March 2020).

[2] Leif Mether, “The Finnish Naming System,” https://tinyurl.com/vk4kbpf, (accessed March 2020).

[3]FamilySearch, Finding Records of Your Ancestors, Part A FINLAND Before 1900 (USA: Intellectual Reserve, Inc., 2001), 7.

[4] FamilySearch, Finding Records of Your Ancestors, Part A FINLAND Before 1900 (USA: Intellectual Reserve, Inc., 2001), 3.

[5] “Communion Book example,” FamilySearch, Part A FINLAND, 4.

[6] Ibid.

Do you have any Finland genealogy work that you need to do? Let us know in a comment below!